Discussing the history of videogame RPGs, one can’t help but notice how global trends are often balanced, if not superseded, by each country’s unique development context. While this is fairly obvious for the United States and Japan, whose output mostly defined the Western and Japanese RPGs monickers many use while endlessly debating their underlying design differences and crosspollinations, there are actually a lot more relevant players in this diverse space, with Korean and Chinese RPGs having their own unique history, franchises and narrative traits in East Asia, while Russia, Ukraine and Poland have followed their own path, for instance sporting a strong adherence to literary and historical sources for their settings compared to most other regions.

The same is true for Western Europe where, for instance, Germany and the United Kingdom ended up having noticeably different trajectories in terms of videogame RPG output, while Italy and Spain regrettably always had a smaller footprint in this genre. Even then, they’re still easier to trace back to the common roots of Western RPGs compared to France, whose RPG output has a number of fairly unique traits that the recent success of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, have made even more obvious.

To understand those peculiarities, we must take a step back and consider some of the French videogame market’s core traits. Compared with most other European countries, France isn’t just one of the major videogame markets, but also has an outsized number of videogame-related companies which have flourished in the past decades thanks to the French government’s unique policies, introduced in late 2003 (well before most other European nations) with the aim of supporting what was back then a budding industry struggling with some early growing pains, not just with strong financial incentives in terms of tax breaks and support, but also with the opening of a National School for Games and Interactive Media (École nationale du jeu et des médias interactifs) and the willingness to present French-developed videogames as cultural objects on the same level as more traditional art forms and media, like novels, movies and fine arts, a bold stance that few other countries have followed since then.

Even President Macron, which famously made a controversial argument against violent videogames as one of the causes behind the June 2023 unrests, ended up backtracking soon after, to the point of claiming that “videogames are an integral part of France” in September 2023, not to mention how, two years later, he was quick to publicly congratulate Clair Obscur’s developers after the game’s stunning critical and sales reception, hailing their success as a victory for French culture. Of course, this isn’t even considering more mundande but still relevant facts, like the close relationship Ubisoft has always enjoyed with the French political and cultural establishment.

This political support for the French videogame industry, which sometimes veers into the diplomatic space when France considers the interest of its videogame companies, among others, when drafting EU policies and economical partnerships with non-EU entities (for instance, facilitating Ubisoft’s ties with Canadian authorities and the regional government of francophone Quebec, both of which granted favorable conditions to Ubisoft Montreal), has allowed this scene to flourish in a way other European States really haven’t been able to imitate, despite a number of other countries’ attempts, like in the last decade or so with Germany’s 2019 improved gaming-related incentives or the United Kingdom’s 2014 Video Game Tax Relief act, also trying to foster their own developers.

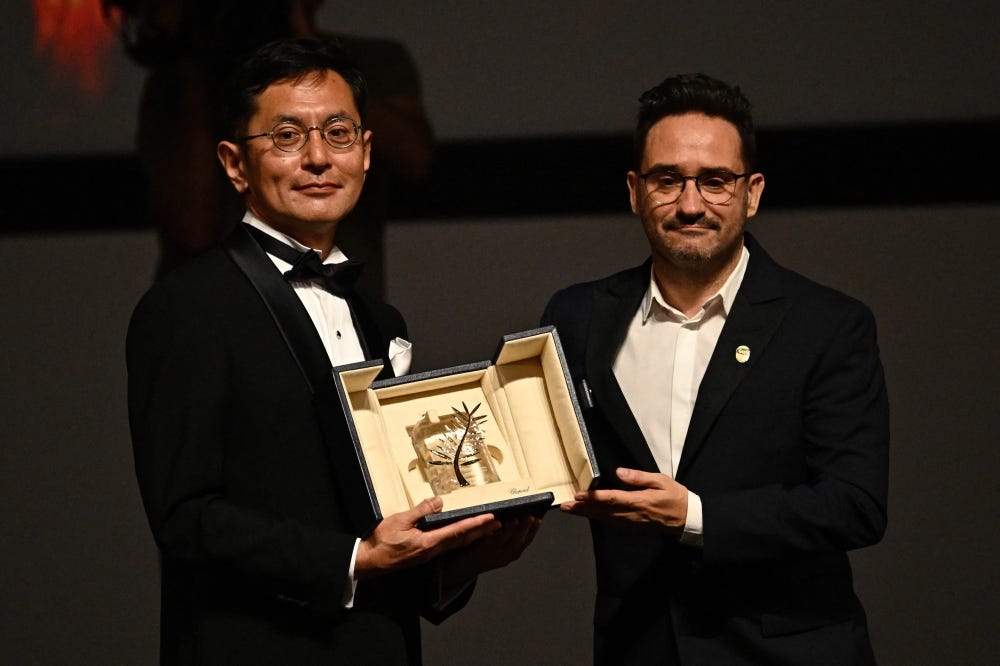

As a very important aside, France is also one of the biggest consumers of Japanese entertainment media, including not just manga, anime and videogames but also movies and literature, which are often seen as particularly compatible with France’s own cultural identity. Again, this also ended up having official undertones, with key figures such as Miyazaki and Murakami being recognized on a variety of levels and Natuski Ikezawa being awarded a National Order for her role as a cultural bridge of sorts between France and Japan. This unique compatibility with Japanese entertainment, already present in the late ‘90s, would later blossom in the early ‘10s in the context of France’s RPG development scene, as we will see in the third part of this retrospective, giving way to an unique duality in the country’s RPG output between Japanese-inspired and Western-inspired RPGs.

-SORCELLERIE’S DONJON CRAWLING

France’s unique history in the vast and diverse realm of videogame RPGs can be traced back to the early ‘80s in two very different strands, one directly influenced by early American RPGs like the Wizardry and Ultima series, the other part of the adventure game family that, back then, was often conflated with videogame RPGs, as we will see.

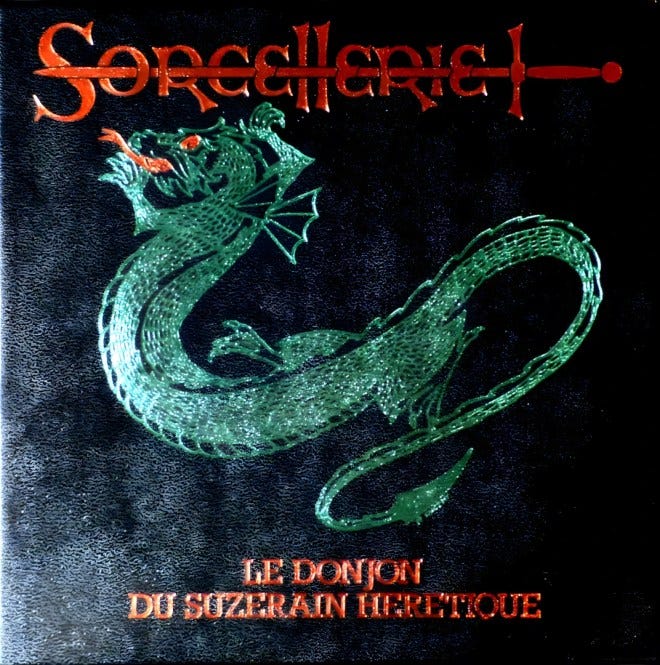

Like with Japan, France also enjoyed an early localization of Sir-Tech’s Wizardry series, which was renamed as Sorcellerie (the first game’s subtitle, Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord, was translated rather liberally as Le Donjon de Suzerain Heretique, meaning “the dungeon of the heretic ruler”) and proved to be a major source of inspiration for French RPG developers in the mid ‘80s, while Ultima had a more muted presence here, with French translations of Ultima II and III apparently having an extremely small print run and Ultima IV being a bug-ridden disaster whose textual interface didn’t recognize English or French commands, meaning it was apparently impossible to complete the game. New World Computing’s Might and Magic, another seminal series born a bit later compared with Ultima and Wizardry, also ended up having an impact on French developers, albeit later on.

1984 was the year when those different trends typical of early French RPG development started to express themselves, first with Tyrann, a Wizardry-style dungeon crawler developed on Amstrad CPC and other early PCs by team Norsoft, a group of friends made up of Remy Gosselin and Matthias Wystrach (with artist Dominique Falue working on the cover art and manual illustrations), which crafted a rather simple experience made up of wireframe first person dungeon crawling and turn based combat handled almost exclusively through a textual interface, without monster sprites.

Compared to Wizardry, Tyrann also offered a simplified pool of just three stats and fewer class options but, despite its rather formulaic nature, it still was the first proper French RPG and served as the basis for a number of future efforts, for instance Norsoft’s own Le fer d’Amunkor, released just two years later on Tangerine’s Oric PCs (which, for a time, was a rather popular platform for French RPG developers), which improved in a number of ways on Tyrann’s blueprint.

The same year also saw the release of Mandragore, developed by a small team led by Marc Cecchi at Infogrames, a new company created in 1983 by Bruno Bonnell and Christophe Sapet (who initially wanted to name it Infogramme, mixing the French words for informatic and program, informatique and programme, later going for an Anglicized take) that would later become one of the main players in the French gaming scene with series such as Alone in the Dark, before starting its complex relationship with Atari and spiraling down into a long crisis that barely stopped five years ago. Instead of focusing on Wizardry, like Tyrann did, Mandragore allowed the party to explore a top down overworld reminiscent of Richard Garriott’s early Ultima games.

Considering how insular game development was back then, though, and how Ultima didn’t enjoy a widespread French distribution (contrasting with Wizardry, which as mentioned had a more robust French presence), one must be cautious in taking for granted those early similarities, as likely as they may seem looking at them almost forty years later. After all, it’s always useful to remember how, even in the context of English speaking developers, in the early ‘80s information about other countries’ RPG efforts was far from granted, like with Chris Roberts only learning about Ultima when he moved from his own Manchester to Garriott’s Austin.

A bit like in Falcom’s future action JRPG Sorcerian, which will be only released three years later, the four-person party featured in Mandragore moves almost as a single man, exploring a number of castles before having a chance to confront archfiend Yarod-Nor, with battles and adventure segments taking on an almost side-scrolling, adventure game-style perspective, compared with the overworld.

-DRAKKHEN, BETWEEN FRANCE AND JAPAN

Some of Mandragore’s early traits would end up resurfacing five years later, in 1989, when another team at Infogrames developed Drakkhen on home PCs such as Amiga and Amstrad ST, a game that many mistake for a Japanese RPG due to the popularity of its console version, developed by Kemco and then re-localized in Europe. Curiously, its French-developed sequel, Drakkhen 2, which would have mixed 3D exploration with side-scrolling, single character 2D action combat, ended up being cancelled, while its Japanese-developed, console-exclusive sequel, Dragon View, was released and cemented the idea of the series’ link to Japan.

From a videogame history standpoint, Drakkhen and its bizarre development history also serve as the earliest link between the French and Japanese RPG development scene, curiously turning a French game into a Japanese one, a trend that will be reversed in the next decades when French developers will end up creating a number of Japanese-inspired titles.

Then again, the original Infogrames-developed Drakkhen featured a number of adventure game trappings that bring us to the other strand of early French RPG efforts, namely French developers’ fascination with adventure games in the early ‘80s, a genre nowadays mostly perceived as removed from traditionally defined RPG subgenres but actually quite prone to a number of hybrid takes back then, when genre labels were less entrenched than today, with adventure interfaces and systems integrated with various kinds of RPGs both in the context of Western titles like Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), a variety of Japanese home PC RPGs (with Ihatovo Monogatari on Super Famicom as a late example) and a number of French RPGs developed in the mid ‘80s, like early Ubisoft RPG Fer et Flamme (1986) and Anneau de Zengara (1987), not to mention the unique Sapiens (1987) by small team Loriciel, created by the Guillion brothers, which mixed an idealized prehistoric setting with a number of systems with RPG, adventure and survival traits and even received an English localization after its strong French sales.

That isn’t even considering how RPGs and adventure games were sometimes seen as intermingled, if not one and the same, by industry giant Sierra’s own marketing effort in the late ‘80s, with Police Quest, the King’s Quest series (ending up with King’s Quest VIII actually incorporating widely acknowledged RPG elements) and even Larry being often defined as RPGs, sometimes as “real RPGs” to mark those based on real-world situations, using RPGs as a broader term defined by its opposition to arcade gaming’s tenets, rather than by its adherence to a set of systems.

In the last decade, the contemporary resurgence of adventure-RPG hybrids with titles like ZA-UM’s Disco Elysium, Obsidian’s Pentiment or a number of Gamebook-inspired titles showed yet again how connected those experiences can be, despite stricter classification efforts being now commonplace both among RPG and adventure game enthusiasts.

- FROM MARTINIQUE TO THE OUTER SPACE

One of the first French attempts to tackle this unique context started back in 1983, even before Tyrann and Mandragore, with a Parisian student still influenced by his experience in the 1968 student protests, Jean-Louis Le Breton, switching from his musical career to be an early videogame developer and creating a number of text adventures, somewhat in line with the early Gamebooks which were very popular not just in English-speaking countries, but also in European countries like Italy and Germany, a niche that to this day influences videogames RPGs with titles such as Russia’s The Life and Suffering of Sir Brante or the Bulgarian videogame adaptation of the US sandbox Fabled Lands gamebooks.

Influenced by Sierra’s Mystery House (1980), Breton released Le Vampire Fou (The Mad Vampire) in 1983, mixing horror, combat-less dungeon crawling and plenty of satire in a text adventure format in what could be said to be the first French RPG-adjacent development effort. Breton, alongside his friend Fabrice Gilles, ended up creating his own company just one year later, in 1984, publishing a number of other works with increasingly political undertones with his Froggy Software label, mostly on Apple II, which was fairly popular in many European countries back then.

While Breton and Gilles were being recognized for their early craft, Muriel Tramis, a woman born in the French Caribbeans on the island of Martinique, also left her unique contribute on this early strand of French adventure games in 1987 with Mewilo, which in many ways is one of the more interesting French titles of that age. The game, set on Tramis’ own native island in 1902, sees the omonymous character travelling to the city of Saint-Pierre to investigate a number of mysterious hauntings related to the death of local slaves during the 19th Century slave revolts, while also discovering the island’s unique culture in the days right before an eruption devastated the island, following a template that is strikingly contemporary in terms of social commentary and pacing despite its age.

This kind of micro-historical take on real world RPG settings, after all, is still very much relevant even today witht titles such as the abovementioned Pentiment, whose adventure mechanics are meant not just to service a story, but also to familiarize the player with a community, its habits, its beliefs and its woes.

Other than its peculiar setting and post-colonial traits, with a huge focus on themes like slavery, plantation labor and creole culture, Mewilo is also a huge step up in terms of art direction and presentation compared with Breton’s works. In fact, due to the talent of Mewilo’s art director, Philippe Truca, the game hasn’t just a huge amount of artworks and backgrounds, but also a very refined interface with dedicated sections, somewhat reminiscent of early Japanese visual novels or adventure RPG hybrids, titles Tramis and her small team likely couldn’t even know existed given how those efforts weren’t really covered by English magazines of the time, let alone French.

Mewilo was also one of the first crossmedia videogame projects, with famed writer Patrick Chamoiseau, a Martinique-born French author which was one of the founder of the Créolité literary movement, acting as a consultant for Tramis and working on a short story included within the packacing. Unexpectedly, Mewilo performed better in the German videogame market (being also one of the first, if not the first, German localization of a French adventure game) than in its own France, possibly because of its own social themes.

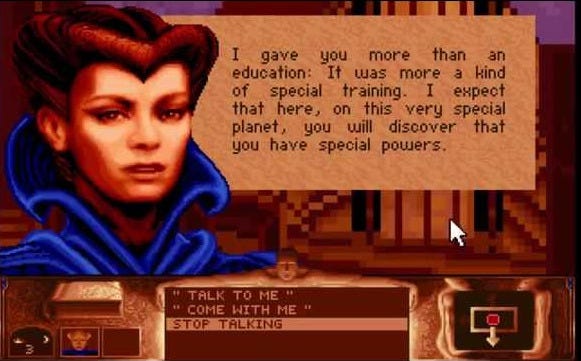

With Breton and Tramis exploring stories with heavy social and political themes, somewhat setting the trajectory for future French developers in an age where more gameplay-oriented experiences were the norm, and proper French RPGs of the late ‘80s often incorporating an unusual amount of adventure elements, it isn’t strange that something similar also happened in the sci-fi space. This context, so far mostly untouched by French developers, was also explored by Philippe Ulrich, which, like Breton, started out as a musician before being enthralled by the potential of Sinclair’s ZX80. After quickly familiarizing with Basic language, Ulrich developed sci-fi RPG-adventure hyybrid Captain Blood (which isn’t related in any shape or form with the omonymous pirate game released in 2025) in 1988 alongside his friend Didier Bouchon, who worked on the game’s art direction.

This became quite an accomplishment for a number of reasons, starting with its Giger-esque art direction, proto-3D graphics (which remind, in turn, of Japan’s contemporary Digan no Maseki and Progenitor on NEC’s home PCs) and incredibly rich and responsive dialogue interface, featuring a whole alien language created by Ulrich, with the ambitious objective of avoiding the frustrating, mangled NPC answers a lot of titles with this kind of dialogue system had back then.

Captain Blood was also one of the most important titles published by an early French publisher with some unique traits, Ere Informatique, which Ulrich joined soon before releasing his sci-fi adventure. Compared with traditional videogame publishers (which, back then, were still a rather new concept, especially in Europe), Ere Informatique, founded in 1983 by Emmanuel Vlau, was a leaner operation which actually acted as a commercial facilitator for freelance creators, paying them with a royalty model while coordinating distribution (including an earlier RPG foray, with late 1984 Wizardry-style L’Antre De La Peur) and also building ties with the British market through a partnership with PSS, ultimately becoming part of Infogrames at the end of the decade. Ulrich himself was apparently very much in favor with the early attempts in bringing French titles to other markets, which also explains his partnership with Vlau.

While those early RPG and hybrid adventure titles were very important for setting up the stage for later French RPG development and, in a way, for France’s overall take on gaming, the videogame medium was so young back then, and its production and distribution models so contextualized in each country, not to mention France’s own signature linguistic insularity, that many of those early titles were only available to French-speakers and were discovered outside France only decades later, much as it happened with early home PC Japanese titles outside their own market.

Of course there were a number of exceptions even back then, like with the abovementioned Ere Informatique, Drakkhen’s unique Franco-Japanese conundrum, Sapiens or Cryo Interactive’s English localization for its Dune adventure game (which also saw Ulrich as its composer), based not just on Herbert’s landmark novel series but also on its 1984 movie adaptation by David Lynch, but this would still remain an issue for much of the ‘80s, with the situation rapidly improving over the ‘90s.

-FLASHBACKS OF THE ‘90s

The ‘90s ended up being a rather quiet decade in terms of French RPG development: most of the early American-inspired efforts seen in the ‘80s died out at the turn of the decade, while adventure games became so prevalent that France ended up establishing its role in that genre, with titles such as the abovementioned Flashback, Dune and Alone in the Dark offering an incredible variety of tones and experiences. In the end, it would take a number of years for French developers to resume tackling RPG development efforts more in line with internationally-affirmed subgenres and design traits, and to start localizing them so that they could be enjoyed outside its borders.

There were, of course, developers that actually went against this trend, like Silmarils, a Lognes-based company founded in 1987 by the Rocques brothers which, for its first few years, only dabbled in the adventure genre, only to rise up to the challenge of RPG development a few years later. At first, they just acted as a publisher and helper for their friends Michel Pernot and Pascal Einsweller, who in 1990 released their first RPG, Crystals of Arborea, but soon after they turned its setting into a proper franchise, expanding on it with the Ishar series, which ended up becoming a rather successful trilogy (including English localizations) with some of the best art direction and in-game graphics seen in the first two decades of French RPGs (Ishar’s cover, which serves as the introductory art for this piece, was so stunning back then that a completely unrelated Austrian metal band, Summoners, used part of it for their debut album, Minas Morgul).

The Ishar series was also notable for revisiting a number of design traits popularized by New World Computing’s Might and Magic (which, by then, had also impacted in the German RPG scene, with Gates of Dawn), providing an almost sandbox-level of freedom to the player, with the game mostly focusing on first person overworld exploration, a day and night cycle with an impact on NPC and shop routines, rather brutal interactions between playable characters (including mutual dislikes and assassination attempts), a number of puzzles and a shared Tolkienesque high fantasy setting (if choosing Silmarils as their company’s name wasn’t enough of a giveaway) which was expanded in each new entry, while also offering a Dungeon Master-style multi character real time combat system.

Some years later, after being forced to cancel Ishar 4, Silmarils went on to develop a radically different game just a few years later, Ubisoft-published Asghan (1998), which ended up going full action RPG while giving a lot of emphasis to its dungeons and puzzle solving.

Another link with this early adventure-focused phase and later RPG efforts was Paul Cuisset’s Delphine Software International which, after developing adventure games like Fantasy Wars: Time Travellers and the smash hit Flashback in 1992, which for a long time was the best selling French videogame, later went on to develop Darkstone, released in 1999, which followed a number of traditional RPG tenets while incorporating plenty of new elements that had surfaced in those years, including one of the earliest use of 3D graphics in French RPGs.

While back then most people considered Darkstone as inspired by 1998’s Baldur’s Gate, the game actually had a very long and troubled development, starting out as Dragon Blade around 1995 when it wasn’t even meant to offer a full 3D experience, and it’s likely its actual influences could be traced back to earlier Western RPGs, with the late entries in the Ultima series and Blizzard’s Diablo (1996) as some likely candidates, even more so considering how Darkstone’s systems aren’t really lifted from D&D-style sensibilities (even more so considering those were the days of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, a very different experience compared with its later editions).

In fact, even the playable classes available for Darkstone’s two player-controlled characters didn’t closely follow in D&D’s example, and the game’s world randomization feature, almost like a nod to the roguelike subgenre, also made it noticeably different compared to most WRPGs of the time.

Darkstone, happily, was also one of the first wave of non-adventure French RPG which ended up being localized in other markets (Cuisset did call his company Delphine International, after all), and was successful enough to justify the development of an expansion and a PS1 port, with a number of differences (like the unfortunate decision to only allow a single player-controlled character). Despite never achieving widespread fame, the game managed to become a bit of a cult hit over the years, even spawning a free to play Android version decades later.

Actually, another lesser known French RPG had been released and localized less than one year before Darkstone, in 1998, even if its development had actually started later compared to Cuisset’s effort. Hexplore, developed by Lyon-based team Heliovision, was an action RPG which mixed some traits of Blizzard’s Diablo and a simplified, non-customizable class system centered upon a number of characters the hero, Mc Bride, could rescue and then choose as allies for the following levels, customizing his party in order to tackle a number of different challenges.

The game’s areas were made by using voxels, a rather popular and nostalgic trend in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, and featured a relevant puzzle element alongside its combat and explorations. Alongside Darkstone, Hexplore was one of the titles instrumental in opening the floodgates for French RPG efforts in the English-speaking markets, finally normalizing localizations and paving the ways for the later efforts of developers such as Arkane in the early ‘00s.

-APRES MOI, LE DOT COM KRACH

Interestingly, though perhaps not surprisingly concerning the small number of French videogame companies back then, Heliovision’s fate actually ended up intertwining with Delphine International’s, when the first, charged up by its success as a developer of Disney-licensed titles, changed its name to Doki Doki Studio and set upon a number of ambitious projects around 2003, like a Sony-published action game focused on the French animation series Dragon Hunters, with an estimated budget of more than 3 million Euros.

Doki Doki’s expansion also saw the Lyon-based company acquire Delphine International around that time, but, unfortunately, this new conglomerate, which by then was briefly one of France’s most important videogame-related companies, including ties to its animation industry, ended up going bankrupt in 2004 as a result of its own overreach and the difficulties linked with the long fallout of the 2001 Dot Com financial bubble, which also affected the European gaming industry.

France’s own CAC40 stock index (a bit akin to the USA’s S&P500), which had reached an all time high in September 2000, cratered in a dramatic way soon after the Bubble popped on the other side of the Atlantic, losing more than 60% of its ATH value before starting to retrace in 2004 (aside from a number of short-lived bull traps in the mid of the crisis). This dramatic fall also ended up impacting in a disproportionate manner most companies linked to software-related themes.

Doki Doki was far from the only casualty among French videogame developers of the early ‘00s, though, with both Kalisto Entertainment and Cryo Interactive closing down even sooner, in late 2002, due to a mix of their own unique circumstances and the unfavorable climate regarding tech-related companies, and Silmarils following them in 2003 (even if the Rocques brothers immediately created a new venture, this time focused on simulation games). This rather dire situation was also key in convincing the Raffarin administration, during President Chirac’s second term, to follow some of the ideas outlined by the APOM (an association of French tech and videogame companies, later known as the Syndicat National de Video Jeaux) in order to save the budding French videogame industry from an early demise and give it the boost which allowed it to thrive in the next two decades, as discussed before.

In the second part of this piece, we will follow the developments born out of those first tumultuous years which defined French gaming, both regarding the exponential growth of traditional RPG development efforts and the increasingly noticeable differences between its Western and Japanese-inspired products, making it one of the more unique and varied European countries in terms of RPG output and leading to the current contrast between efforts such as Spiders’ Greedfall and Clair Obscur.