Developer: Obsidian

Publisher: Xbox Game Studio

Director and scenario writer: Josh Sawyer (Icewind Dale, Icewind Dale 2, Van Buren (cancelled), Neverwinter Nights 2, Alpha Protocol, Fallout New Vegas, Aliens RPG (cancelled), Pillars of Eternity, Pillars of Eternity 2)

Art Director: Hannah Kennedy (Pathfinder Adventures, Outer Worlds)

Composer: Alkemie Early Music Ensemble

Genre: Adventure RPG

Progression: While the game follows a set progression regarding its story arcs, the way they unfold is deeply influenced by the player’s choices and by the way the in-game time is allocated between competing story events.

Developer’s country: USA

Platform: XBO, XBS, PC (15\11\2022), PS4, PS5, Switch (22\2\2024)

Status: Completed on 20\11\2024

Even if I didn’t have a long-standing historical interest in the Holy Roman Empire, the fascinating intricacies of its laws and the relationships between its many States and its core institutions, I would be hard-pressed to find a setting, historical or fictional, with such a sterling track record for videogame RPG adaptations.

The first Holy Roman RPG I had a chance to play, long before I had any serious interest in the empire itself, Darklands, is an oft-forgotten 1992 milestone for CRPGs and one of the brightest jewels in MicroProse’s admittedly crowded crown, while Warhorse Studios’ 2018 Kingdom Come: Deliverance provided an incredibly fascinating simulative sandbox experience set in a troubled corner of that Kingdom of Bohemia that became an imperial Electorate with Romanorum Imperator Charles IV’s Golden Bull and was instrumental to some of the most important events of imperial history for the next three centuries. Of course, paraphrasing Agatha Christie, just two games could be seen as a clue about the truthfulness of my previous statement, but with a third game they could finally make up a proof. And indeed, the last piece in this imperial trifecta is Pentiment, released in 2022 and developed by an Obsidian team led by Josh Sawyer, who saw the game as a passion project after years spent on the Pillars of Eternity franchise.

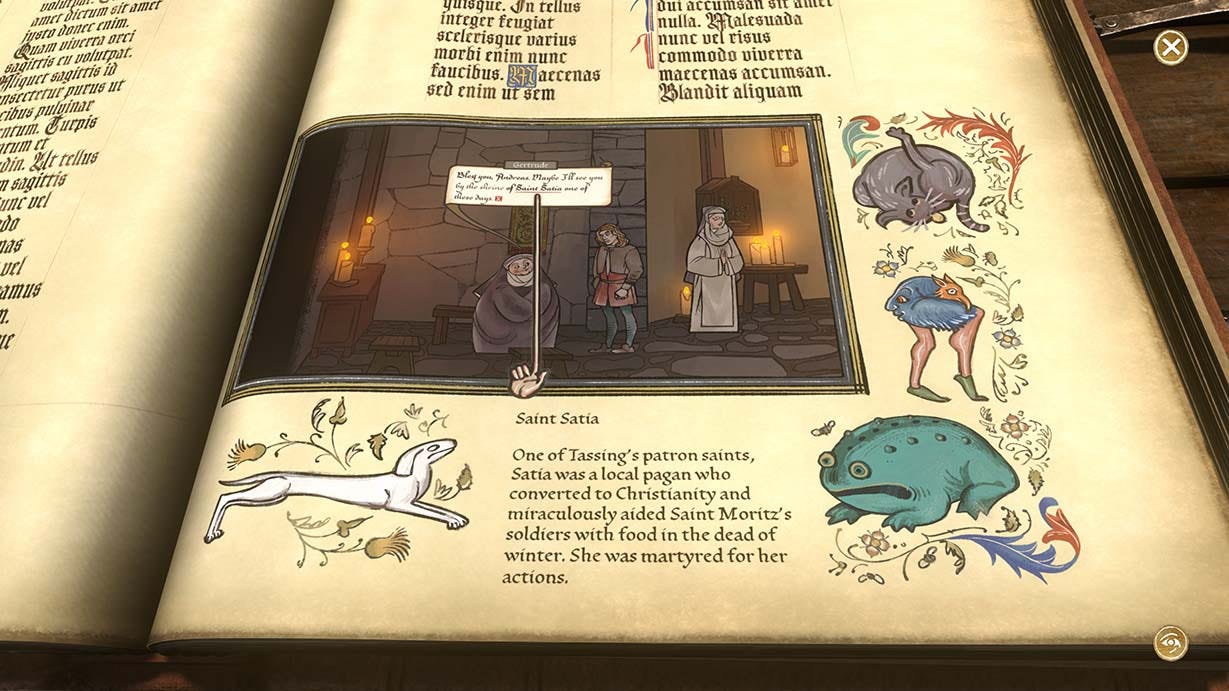

Compared with Darklands and Kingdom Come, both of which placed a huge emphasis on exploration, combat and intricate mechanics, Pentiment follows a completely different design philosophy, much more akin to an adventure game-style RPG that doesn’t just reduce the emphasis on combat, like Planescape Torment or its spiritual sequel Numenera did, but completely reworks RPG tenets such as character growth to make them fully functional to its narrative. In this regard, Pentiment feels like a mix of some of the core design concepts found in two recent Eastern European RPGs, ZA/UM’s Disco Elysium and Sever’s The Life and Suffering of Sir Brante, with an unique art direction inspired by medieval manuscript illustration later featured in Polish tactical RPG Inkulinati (whose developers acted as consultant during Pentiment’s development) and a robust helping of themes heavily reminiscent of Umberto Eco’s Il nome della rosa.

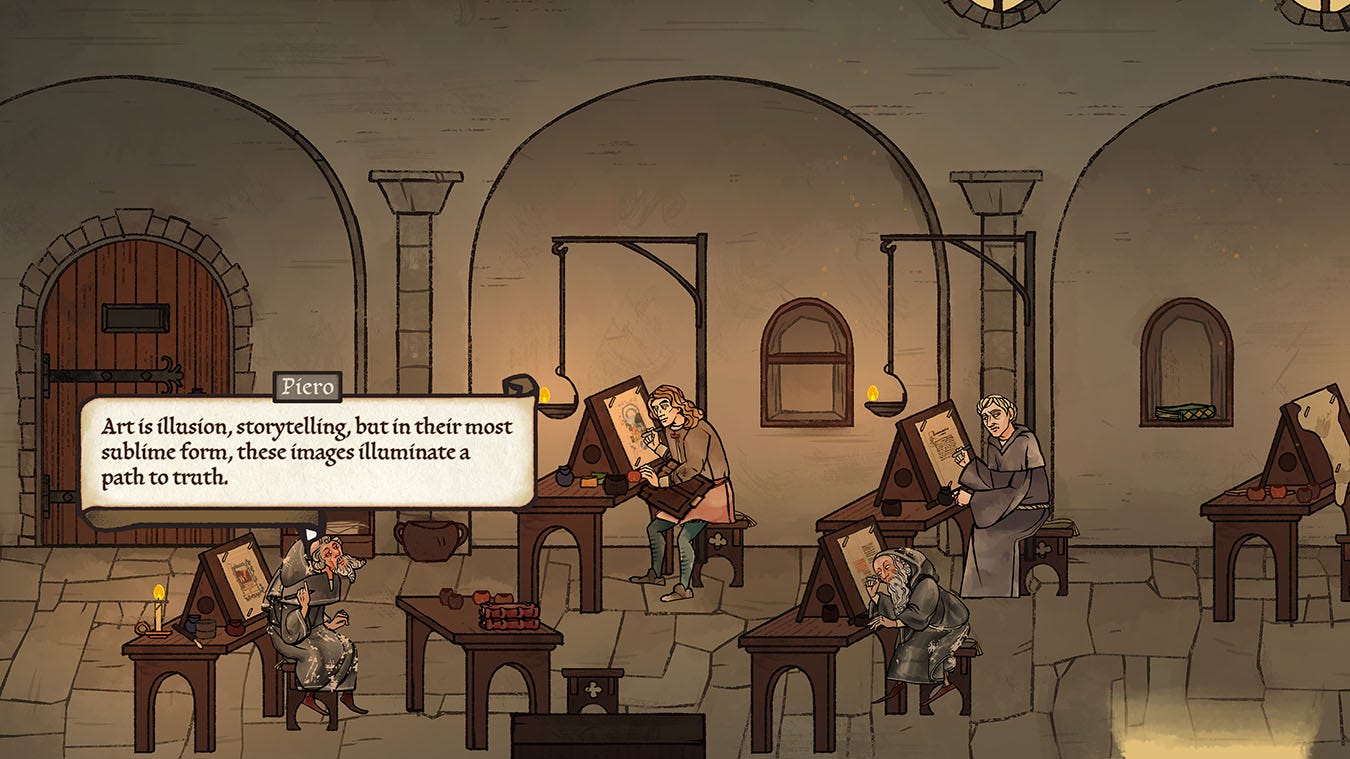

Starting in 1518 in the fictional imperial fief of the abbey of Kiersau, whose Abbot, ruling over the village of Tassing, is under the dual authority of the Prince-Bishop of Freising and the Duke of Bavaria, Pentiment has apprentice illustrator and painter Andreas Maler, possibly inspired by the legendary Albrecht Dürer, working in the abbey’s scriptorium, the place where monks copied manuscripts for long centuries before printed press made their craft obsolete and economically unviable, a transition that is still undergoing during Pentiment’s first act and slowly becomes one of the key themes of its narrative.

While Pentiment lacks any kind of traditional RPG character growth, as mentioned before, our Andreas still can establish himself in a number of different ways. Same as with The Life and Suffering of Sir Brante, the background and skills chosen by the player for Andreas won’t just influence dialogue opportunities, but also the way Andreas will develop in the hyatus between Pentiment’s first two Acts, including the birth of new combination skills, another of Brante’s key design choices. While Pentiment’s third act follows a different pattern for reasons I won’t spoil, even there the player has some wiggle room to determine yet another set of skills long before that part of the story even starts. Also, same as in Disco Elysium, our Andreas will have a veritable choir of mental interlocutors, both in his dream sequences and during some of his inner monologues, with Socrates, Dante’s Commedia’s Beatrice, mythical Ethiopian Emperor Priester John and Saint Grobian providing different, often contradictory perspectives on the events he is forced to face.

After taking some time to establish the game’s setting and its large cast, consisting of the Kiersau abbey’s monks, the nearby convent’s nuns and the Tassing villagers, including the Gertner family that is renting Andreas a room during his stay, the story will kick off with the murder of Baron Rothvogel, an imperial aristocrat whose complex personality, mixing traits of genuine amability and intellectual curiosity with unspeakable brutality, shows how Pentiment isn’t afraid to present complex, morally grey characters. Having just two days to find the culprit in order to clear the reputation of Brother Piero, the monk and scriptorium artist that mentored him and ended up being implicated in the assassination, Andreas will have to briefly turn into an unlikely investigator, with a rather brutal time limit forcing him and the player to follow just some of the many leads available. What will unfold, regardless of Andreas’ actions, is a complex, multi-faceted story unravelling throughout the decades, with two long hyatuses separating its different chapters.

While the mysteries of Kiersau and Tassing pile up to a critical mass, the player will be offered glimpses of many historical events that rocked the Holy Roman Empire during those troubled years, with Martin Luther’s theses and their impact on the Catholic Church and imperial political landscape, the Peasants Revolts and their tragic outcome, the reorganization of the Swabian League, the birth of modern press and its consequences on literacy, ideological and religious debate and the obsolescence of manuscripts and their economic and cultural monastic context, not to mention themes like the relationship between farmers and burghers, the role of women in different societal contexts and the evolution of local identity from a cultural and religious standpoint.

Pentiment’s story and setting were obviously developed with plenty of love, not to mention a noticeable care for historical plausibility, even regarding details such as taxation, imperial laws and the relationship between different estates, while still being careful to avoid aiming too high and to distract its audience from the small scale the events are focused on: for instance, the Battle of Pavia is casually namedropped by a wandering Landsknecht during an optional event and Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V are never named aside from a single reference, same as any other major imperial political player of the time save for the Wittelsbach Dukes of Bavaria.

Instead, because of the well-learned characters Andreas has to deal with in his line of work, the game isn’t afraid to deliver countless literary, philosophical and theological references, some of which obviously depend on Andreas’ chosen background traits, and to show quite a number of lavishly rendered manuscripts during his stay in the Abbey and his investigations. This doesn’t just concern European manuscripts: one of the game’s most unique events, a priest from the Ethiopian College in Rome giving an homily to Tassing’s populace before he departs from the Abbey where he was staying as a guest, is rendered in the unique style of the Axumite religious manuscripts. Later on, when printed press is established, woodcutting and typesetting are also explored in detail.

It’s a bit unfortunate, then, to see how this dedication to historical accuracy doesn’t always match with the attention given to Pentiment’s own scenario and the way it is shaped by the player’s choices, likely because of the usual mix of issues caused by a small budget and development quandaries starting to pile up when the outcomes of different branching scenarios risk varying so wildly as to require an unsustainable amount of alternative, possibly very different assets, characters and events. The main example is the end of the second Act that, while narratively powerful in its own right, unfortunately ends up feeling a bit underwhelming in terms of choices and consequences since it ends up playing out almost identically regardless of Andreas’ choices and investigations (more details in the footnote, with a SPOILER warning1), an issue one could also have with the first Act’s ending, albeit on a much smaller scale due to the very different scope of the unfolding events.

Less dramatically, there are also some conversations where your character’s possible answers seem a bit too much focused on a single outcome, like with a dialogue between Andreas and Ulrika about old pagan customs where even a player who choose a theological background can’t dissuade the girl from pursuing interests which, at the time, would have been seen as idolatry, something that would unite in horror both Catholics and Lutherans (there’s an option acknowledging those are dangerous topics to explore, at least). Also, despite playing the game two years after its release, I still experienced some rather obvious issues regarding quest progression and dialogue coherency, most noticeably with the events surrounding brother Guy in Act 2 and, later, with the twins in Act 3, which stands as proof that, as different as it is, Pentiment is still an Obsidian game.

Despite those small blemishes, Pentiment’s relevance in the broader RPG space is still difficult to overstate: not only does it questions lots of assumptions about CRPGs, and RPGs as a whole, by mingling on a conceptual level with adventure game design elements while foregoing ones typically perceived as RPG staples, but it isn’t afraid to present a complex historical setting without dumbing it down by either offering a poorly researched script or by focusing only on major historical events while forgetting about the daily minutiae of those who actually lived those times. Rather, Sawyer and his team choose a narrative approach akin to the historiographical current known as microhistory as imagined by Levi and Ginzburg, hinting at the larger world behind the game’s Alpine setting, slowly unveiling Tassing and Kiersau’s many layers of history and falsehood, while at the same time focusing on the small, mundane histories of common people which, ultimately, serve as the threads to Pentiment’s fascinatingly immersive tapestry. One of the ending sequences, which is also an heartfelt tribute to one of Andrey Tarkovsky’s best works, Andrei Rublev, shows exactly how the daily life of a community made up by individuals and families intertwine to form a community’s historical, cultural and religious shared identity.

SPOILERS for the end of Act 2: One could understand Lenhardt trying to protect Hannah if Andreas chooses to accuse her, even if that is still a bit of a stretch since he was never depicted as romantically involved with her or interested in her well being, but there’s really no reason Brother Guy should escape to Lenhardt’s mill if the player indicate him as the culprit, nor for Lenhardt to risk his life and livelihood to defend someone he didn’t care about, someone that would actually serve as a great scapegoat to appease the peasants while leaving the Abbey unscathed and preserving the status quo. This gets even worse if the player accuses Matthias: not only does Lenhardt protecting him make no sense at all considering how he tried to frame Matthias with all his might just a few hours before, during the optional hunt event, but Matthias (or rather Jorg) himself has really no reason to run to the mill, even more so considering how his past should make him more apt at running away from sticky situations.

The game trying to pass Lenhardt’s actions as an attempt to spite the peasants by depriving them of their attempt at mob justice could make some sense, if it wasn’t reused word for word in three very different situations and if the game didn’t show him dramatically outmatched, with just a flintlock against the whole village and the Duke of Bavaria’s troops still too far to save him. As it is, one can understand how the developers didn’t want to branch the story too much by offering drastically different outcomes that would create the need for a much more complex and diversified Act 3, but still I think the way they handled that event was a letdown compared to the rest of the game.