In the first two parts of this retrospective about the history of French videogame RPGs, we had a chance to discover the first pioneeristic effort of the mid ‘80s, the lull of the ‘90s, the disruption caused by the Dot Com crash in the early ‘00s and, later on, the resurgence of French Western-style RPG effortsin the early ‘00s due to a number of diverse French companies like Arkane, Spiders, Streum On, Cyanide, not to mention Ubisoft itself.

Then again, it’s now time to complete our journey in this fascinating context by tackling one of the most peculiar traits of French RPG development, its strand of animation-themed and Japanese-inspired titles, which developed concurrently to the efforts of the likes of Colantonio and Rousseau but occupied an adjacent, mostly unrelated space, with little cross-pollination between teams and individual developers despite both happening at the same time in the context of France’s game development scene.

We will also consider how Japan reciprocated France’s own interest, and how a number of titles ended up incorporating developers from both countries, despite being widely considered French or Japanese efforts, with Infogrames’ Drakkhen (1989), a French Amiga RPG which was retooled (and even given a sequel) in Japan for its Super Famicom release until it ended up being perceived by many as a Kemco franchise, as one of the earliest examples.

-JAPANESE RPGs IN FRANCE

Before tackling Japanese-inspired French RPG development efforts, it’s best to consider how Japanese RPGs themselves happened to get into the French market, and how they were able to influence it and the generations of young French enthusiasts that will later end up working in videogame development, in a number of ways.

While American RPGs had an early start in France, with Wizardry (renamed as Sorcellerie, as we discussed) and Ultima having a number of French localized releases since the mid ‘80s, not to mention Might and Magic, which ended up becoming a French series later on when Ubisoft acquired it and made Colantonio’s Arkane work on Dark Messiah, Japanese RPGs didn’t enjoy the same headstart. This was actually an issue for most European countries from the early ‘90s to the early ‘10s, not just because a sizeable majority of English-translated Japanese RPGs ended up not being published in Europe at all for a variety of reasons mostly related to logistical issues, but also because most of those who did only retained the English localization created for the American markets and weren’t localized in European native languages such as Spanish, Italian, French or German, meaning their audience was reduced from the very onset, especially in the early ‘90s where English proficiency wasn’t as common as it’s today even among the younger generations in continental Europe.

At the time, after all, internet had yet to become a thing and most popular entertainment was consumed through books, cinemas and TV shows presented in each country’s native language, which obviously was also true for Japanese manga and even animes, which were mostly consumed on TV or, especially when it came to more niche series, via VHS tape releases.

Then again, while Europe never got Final Fantasy I or the Dragon Warrior games on NES, nor Final Fantasy II and III (aka IV and VI) or Chrono Trigger on SNES or Tactics Ogre, Final Fantasy Tactics, Xenogears or Chrono Cross on PS1, just to name a few glaring examples, there was still a vibrant import market aimed at the small but passionate niche of genre fans that tried to keep up with English releases, with a few copies of US-published JRPGs being available in select shops in major European cities and a variety of ways to play them on PAL hardware, be it the clunky SNES cart adaptor that I still love to this day or the hardware modifications a number of shops carried out for PS1 or, if you searched hard enough, even Sega Saturn.

While things slowly changed after Final Fantasy VII’s overwhelming success showed Japanese companies there was also a sizeable European audience for their titles, there were still a number of early attempts that showed the French market’s love for this genre, mostly focused on Super Nintendo, since Sega of France didn’t really bother with European localizations for its JRPG Mega Drive lineup, like Shining Force 1 and 2 or the Phantasy Star games.

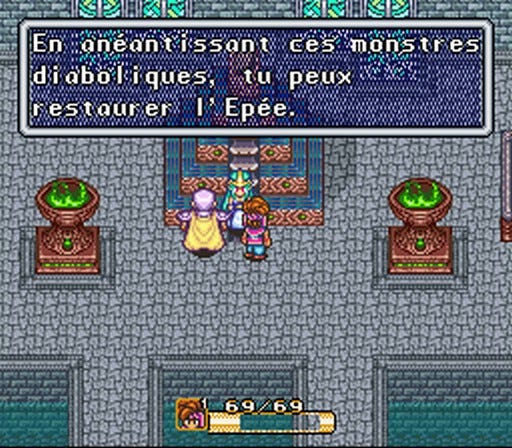

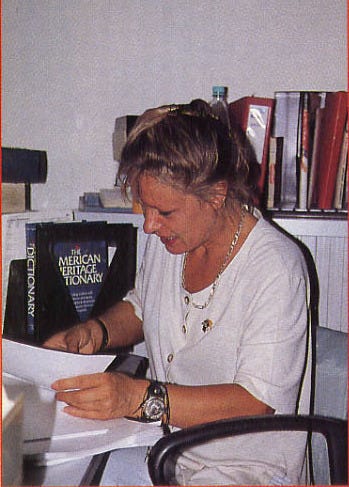

Squaresoft’s Secret of Mana (1994) on SNES, for instance, was one of the first high profile JRPGs to receive a complete French localization for its PAL release. This translation was based on the English script rather than on the original Japanese and, like most videogame translation back in the days, was handled in a very short timeframe, with Nintendo of Europe’s French translator, Veronique Chantel, who previously worked on A Link to the Past’s translation, having just two months to wrap up the script of Koichi Ishii’s landmark action JRPG while also facing a number of technical issues due to the higher number of characters required by the French script compared with the English one.

Compared with Secret of Mana, Quintet’s Terranigma (1995) was even more significant in this regard, since it wasn’t just a relevant SNES action JRPG release receiving a French localization, but also a game that was only localized in Europe, completely skipping the American market for a variety of narrative reasons due to its contents, pushing to the limit the para-theological, somewhat dualistic narrative elements already found in previous Quintet titles.

While Terranigma ended up becoming a beloved classic, including for yours truly, its release window happened to be very unfortunate from a purely commercial standpoint: while the English language European version was published by Nintendo in late 1996, the Spanish and French-localized carts only became available much later, with France only getting the game in summer 1997, at the tail end of Super Nintendo’s lifespan and with Final Fantasy VII’s European November 1997 release already looming on the horizon.

Given how Veronique Chantel had translated Quintet’s previous game in the Soul Blazer pseudo-series, Illusion of Time (known in the US as Illusion of Gaia), one could assume she would return to work on Terranigma, too, but by then she had been unfortunately fired by Nintendo of Europe, with Quintet itself organizing their new title’s European translations, which likely played a factor in the game’s delayed French and Spanish releases.

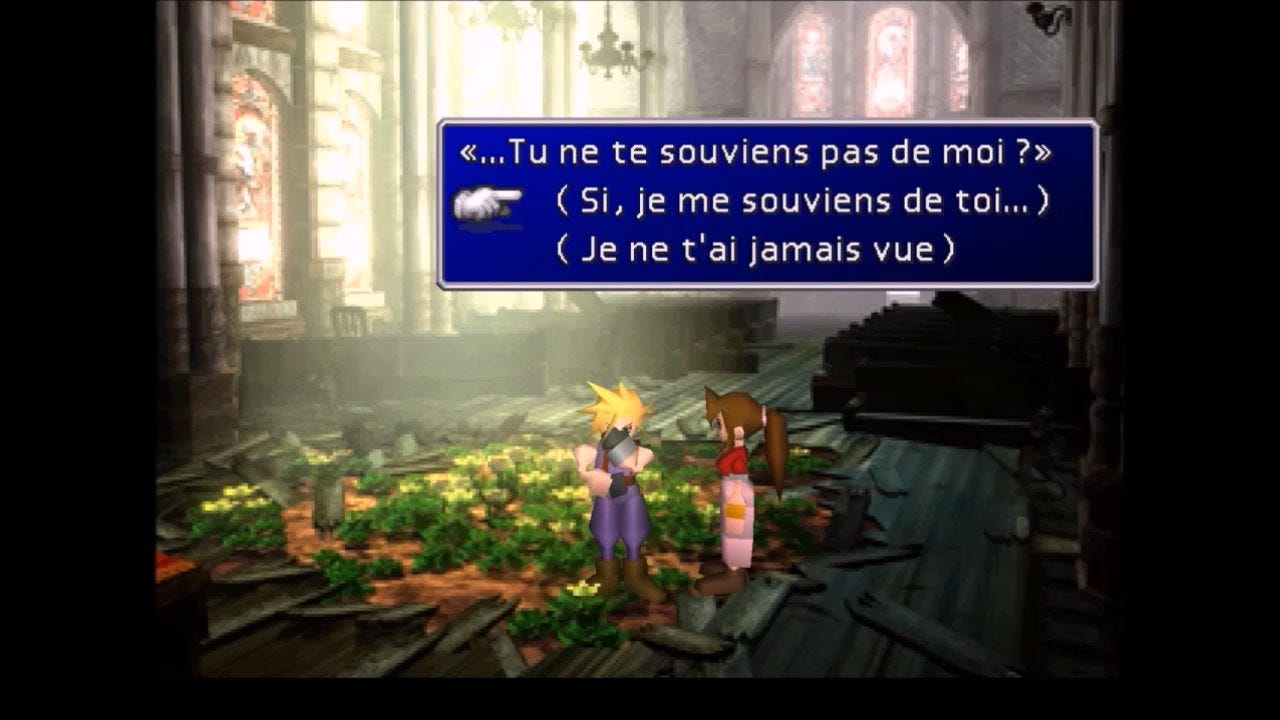

As mentioned, though, it was Final Fantasy VII that really changed the JRPG landscape in France, not just because of its incredible popularity and marketing (which was shared by most other European countries, with Italian console magazines, for instance, being flooded by the sheer hype about the game despite it not being even translated in that language), but also because it was localized in French alongside German and English. While its French localization was far from ideal, prompting a later re-translation effort from a fantranslation team, it still allowed a large audience to familiarize itself with a franchise that most people in France (and, indeed, Europe), outside of small import-focused circles, had never had a chance to discover outside of some news blurb on videogame magazines or Final Fantasy-branded GameBoy Western releases of what were actually entries in the Seiken Densetsu and SaGa series.

While Europe would only achieve JRPG release parity with North America much later, in the mid ‘10s, when American-exclusive JRPG localizations became rarer and rarer and smaller European publishers joined to fray to make most English-localized titles also available in the Old World, FFVII’s release can still be seen as the moment things finally shifted in the right direction and Europe slowly started getting more and more titles published locally, if not localized in our own languages.

-ANIMATED ADVENTURES

Aside from the growing popularity of Japanese entertainment and RPGs in the French market, the other trend contributing to the rise of Japanese-themed French RPGs was actually mostly based in French culture itself, namely the crosspollination between its animation and videogame industries. This was kickstarted by Lyon-based Heliovision in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, when the success of their Disney-themed outsourced titles led them to grow into Doki Doki while acquiring a number of other companies and attempting to bridge French animation and gaming, even if the Dot Com crash unfortunately unraveled that effort.

Just a few years later, though, with the State-based incentives for the French videogame industry having been introduced by the Raffarin administration, it was time for another attempt, which ended up making a much bigger splash. In 2004, Roublaix-based Ankama Games ended up making waves in the rather young MMORPG space with Dofus, a Flash-developed, browser-based turn based title initially released in France and then internationally in 2005 which soon attained massive success, ranking among the ten most successful MMORPG games a few years later while achieving millions of active players.

While Dofus originally started out with a more stylized art direction, somewhat reminiscent of French cartoons in its key arts (even if, early on, I still immediately noticed a stylistic continuity with the design works of Sega’s Yoshitaka Tamaki for series such as Shining Force and Landstalker), it gradually transitioned to a more Japanese-inspired art direction over the years, with its latest Unity-based version making this shift rather obvious.

Ankama’s success in the MMORPG space with Dofus led it to yet another French attempt at mixing its own animation and videogame industries, with Wakfu, a sprawling 2008 animated series set as Dofus’ distant sequel that lasted more than a decade and, curiously, was released well before its omonymous game, yet another MMORPG, though this time developed in Java.

Dofus and Wakfu, not to mention their animated series, companion merchandise and expanded universe, weren’t just a landmark for the French videogame industry, but also a huge influence for many French developers, moving the country’s RPG development in the direction of more cartoon and stylized art directions in the same decade when Japanese entertainment, already way stronger in France than in most European countries, was becoming an even bigger influence not just in the manga and anime space but also regarding Japanese RPGs.

This broad trend towards artistic stylization also touched on Western-style French RPGs, as discussed, especially considering the first few titles developed by Jeahanne Rousseau, like Monte Cristoìs Silverfall and the early Spiders RPGs with their cel-shaded art direction (possibly influenced by JRPGs like Wild Arms 3 or Dark Cloud 2), which was still somewhat apparent in Mars War Logs before the shift to realism with their later efforts.

A third source for this shift, aside from France’s own cartoon-inspired RPGs and the popularity of Japanese entertainments, could also be traced back to the increasing relevance of Japanese-inspired indie RPGs in the ‘00s, starting with the European RPG Maker scene and continuing on with more structured development efforts later on, not to mention the emergence of Japanese-inspired Western RPGs like Anachronox or Septerra Core.

-LA PUCELLE DE TOKYO

Interestingly, in the same timeframe, Japanese RPG developers of the ‘00s weren’t shy of using France, mostly due to its historical, artistical and touristical relevance, as a setting for their own RPG efforts, even when those weren’t even planned to get a Western release, like with 2001’s Sakura Taisen 3 (whose Eiffel Tower-themed key art served as this article’s cover). Ominously subtitled “Is Paris burning?”, a reference to Hitler’s question to the city’s military governor when the German army had to leave the city, Sakura Taisen 3, the Sega franchise’s Dreamcast debut, moved the series’ unique mix of visual novel, theatrical performances and mecha-based tactical combat to the French capital.

Paris was also featured in Shadow Hearts Covenant (2004) on PS2, not to mention Level 5’s Jeanne D’Arc, a tactical JRPG set during the Hundred Years War, Pokémon X and Y, whose director, the self-described Francophile Junichi Masuda, based the game’s setting, the Kalos region, on France itself, and that isn’t even touching on Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII’s ending sequence. Even Chinese RPGs chimed in much later with Banner of the Maid, which mixed the French Revolution and early Napoleonic Age with a fairly unique tactical RPG shell.

-THE RISE OF FRANCO-JAPANESE RPGs

While the attempts to develop French games using stylized art directions, often building joint efforts with France’s animation industry, the growing success of Japanese entertainment and Japanese RPGs and the benevolent stance of Japanese companies regarding the French market were all disjointed phenomena, they still ended up contributing to the rise of a new generation of French developers which, instead of basing their efforts on traditional Western RPGs, like Colantonio did with Ultima Underworld or Rousseau with Diablo, choose to create new experiences which attempted to bridge French and Japanese sensibilities, sometimes even mimicking Japanese RPGs in a number of relevant ways.

That this was an organic trajectory felt by many different French developers becomes even clearer considering how most of those efforts materialized in the early ‘10s from a variety of unrelated teams, each striving for slightly different goals despite working in what will soon become a common space. Like with French Western-style RPGs, we will see how even the strand of Japanese-inspired RPGs will often end up involving Francophone Canadian developers from Quebec, starting with Ubisoft Montreal’s Child of Light (2014).

While Ubisoft Montreal was, and still is, one of the heavy-duty studios of Ubisoft, later having a pivotal role in Assassin’s Creed’s gradual shift toward the inclusion of RPG elements, it also took part in the company-wide effort to develop a number of passion projects like Valiant Hearts, trying to catch the newfound enthusiasm for indie games while still being publisher-led efforts.

Child of Light’s development was led by Patrick Plourde, previously the director of Assassin’s Creed Brotherhood, which in 2012 felt he had earned the chance to make a pitch and, inspired by Ubisoft’s French efforts, like Rayman or From Dust, not to mention the rising popularity of indie titles like Journey or Limbo, tried to champion a smaller, more focused RPG development effort where Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy VI and Yoshitaka Amano’s art was some of the main inspirations. Ubisoft, already trying to position itself as a developer with a multi-level strategy including mainstream releases and boutique efforts aimed at niche audiences, was happy to greenlit the project, allowing Plourde to work for two years with a tight-knit team of around twenty developers, a huge departure from his previous projects, which all involved a much larger workforce.

Child of Light’s art director, Thomas Rollus, expanded the game’s range of artistic inspirations, being influenced by both Japanese sources like the art of Yoshitaka Amano and Studio Ghibli (while they never mentioned Popolocrois as a source, it’s also interesting to remember how its remake had just been localized on PSP) and French illustrators like Tolouse-born Edmond Dulac, who specialized in surrealistic and fairytale subjects, trying to combine different cultural and aesthetic sensibilities for the game’s fairtyale themes.

Likewise, Child of Light’s game designers, Aurelie Debant and Melissa Cazzaro, took a number of inspirations from a variety of Japanese RPGs, with platform side-scrolling traversal likely inspired by titles such as Valkyrie Profile and Odin Sphere (not to mention plenty of older side-scrolling JRPGs) and an active time battle system taking more than a few pages from a cult classic like Game Arts’ Grandia, despite Plourde initially being influenced by Final Fantasy XIII, by then still fairly recent.

- PARISIAN WONDERS

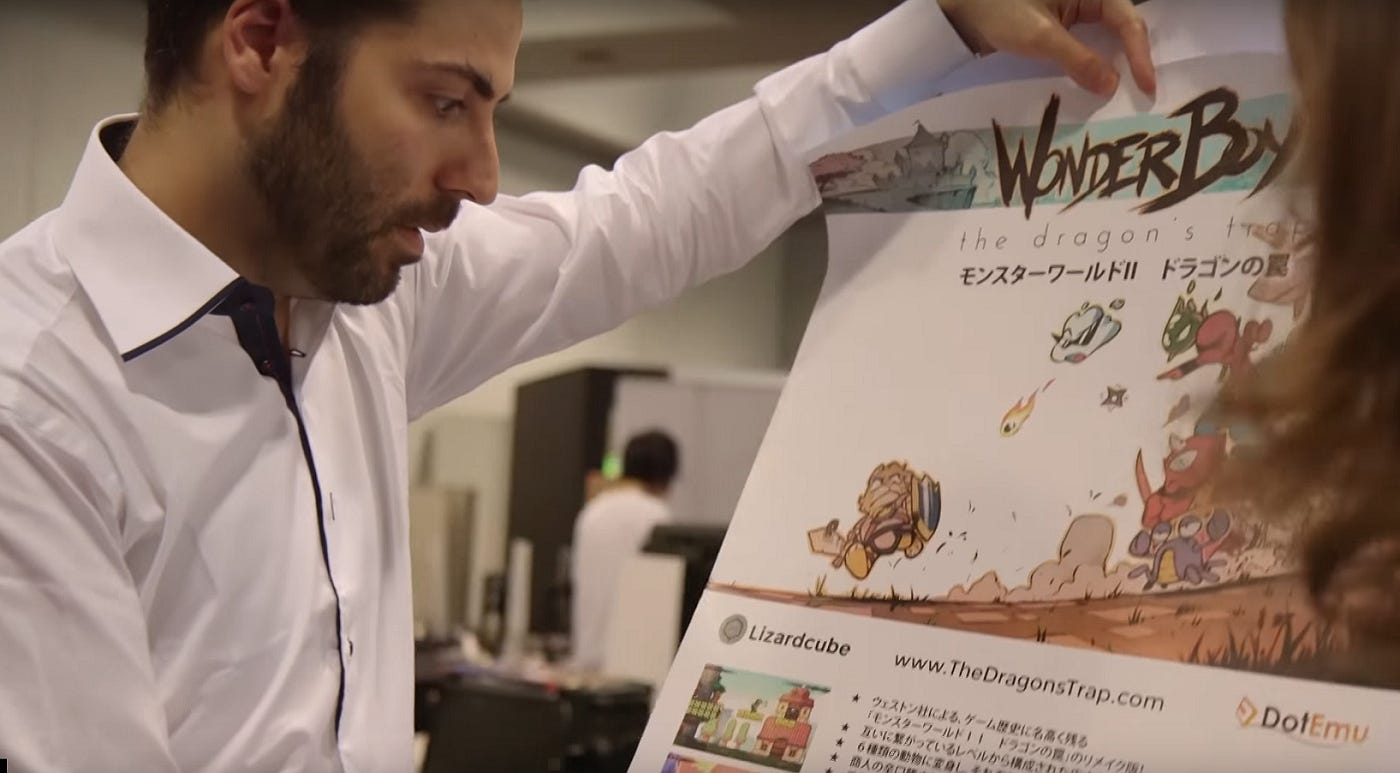

While Child of Light, with its poetry-like dialogues, fairytale tone and peculiar systems was a success, a number of other similar efforts were already underway in the French-speaking development world. In 2013, Parisian game developer and Sega-enthusiast Omar Cornut, who had worked on a Master System emulator in the late ‘90s, started reverse engineering one of the early classics in the side-scrolling action Japanese RPG subgenre (in many ways a precursor for the traits now associated with Metroidvania games), Westone’s Wonder Boy III: Dragon’s Trap, an effort that later ended up including a number of other passionate developers, slowly turning into a pitch for a full-fledged remake.

While they tried contacting the original director, Westone legend Ryuichi Nishizawa, it wasn’t until they sent him a number of concept experiments for his 50th birthday that he truly took an interest in their effort, ending up supporting it and helping them secure a proper deal after Cornut and his friends created their own company in 2015, Lizardcube, and gained the support of publisher Dot Emu.

What came out two years later was one of the most faithful celebrations of an 8bit classic, with a gorgeous 2D graphics that mixed a remarkable loyalty to the original with a peculiar French style while also guaranteeing the ability to immediately switch from the original to the remake. Cornut’s belief about Dragon’s Trap still being able to stand on its own due to its timeless charm was fully vindicated by the game’s great reception, soon becoming a niche hit that helped spotlighting Lizardcube’s talents, opening the gate for their next deal which would allow Cornut and his friends to work on Streets of Rage 4, with remarkable results.

France’s relationship with the Wonder Boy series was actually fated to continue with a completely different effort by the Paris-based Game Atelier team, which initially started its development in the early ‘10s as a Wonder Boy-inspired sequel to their own IP, Flying Hamster, later scrapped and repurposed as a full-fledged part of Westone’s old series, Monster Boy in Cursed Kingdom (2018). While the core team was made of French developers coordinated by director Fabien Demeulenaeare, series creator Nishizawa also helped out during Monster Boy’s development, not to mention how its soundtrack was also handled by a team of Japanese legends like Yuzo Koshiro, Motoi Sakuraba and Michiru Yamane, helping out French composer Cedric Joder.

Compared with Lizardcube’s extremely faithful remake effort, Game Atelier could take more liberties considering they were working on a brand new game, and they tried to incorporate even more Metroidvania-style elements while still staying true to the series’ unique identity, a choice that ended up being quite successful, making Monster Boy a critical hit and a decent success on a commercial level.

-MELODIES OF FRANCE

While Child of Light and the Wonder Boy inspired titles remake were remarkably successful, at least in their own niche, it would be historically inaccurate to say they were the reason for the later French efforts in this design space, since a number of those were already underway before they were even out, and the dynamism shown by the French videogame industry at large, including in Western-style RPG efforts like Arkane and Spiders’ titles in the ‘10s, showed how diverse and dynamic this context was.

For instance, a small studio called Enigami, based in Haute France’s Tourcoing and created by Japanese enthusiasts Hazem Hawash and Samir Rebib, was working since 2015 on yet another French-developed Japanese-inspired RPG, choosing a completely different angle compared with Plourde and Cornut’s efforts. Shiness: The Lightning Kingdom, released in 2017, mixed full 3D explorations, a setting featuring a mix of anthropomorphic and human characters and an action-based combat system reminiscent of Legend of Legaia, with Hawash and Rebib also mentioning Skies of Arcadia, the Mana series and anime fighters as some of their inspirations.

Anthropomorphic animals in JRPGs had been championed long before by a number of series, with Capcom’s Breath of Fire as one of the main early examples, not to mention CyberConnect2's Little Tail Bronx series, started with Tail Concerto on PS1 and later continued by Solatorobo on Nintendo DS. Interestingly, its later entries, the Fuga games, were actually directed by a French developer who had travelled to Japan in search of new experiences, Champse-sur-Marne born Yoann Gueritot, who we met in the second part of this retrospective as part of the QA effort for Cyanide’s Game of Thrones RPG adaptation.

Gueritot’s gaming proclivities are very interesting, since he noticed how his early experiences were almost completely focused on Japanese RPGs JRPGs such as Final Fantasy VII, Grandia, Suikoden 2, Vagrant Story or Valkyrie Profile (not to mention another favorite of him, Sega’s Shenmue) being some of the foundational titles that later influenced his career, while he only found out about Western RPGs much later, showing how the split I mentioned earlier regarding French RPG developers influenced by American or Japanese games was already a thing for people born in the late ‘80s.

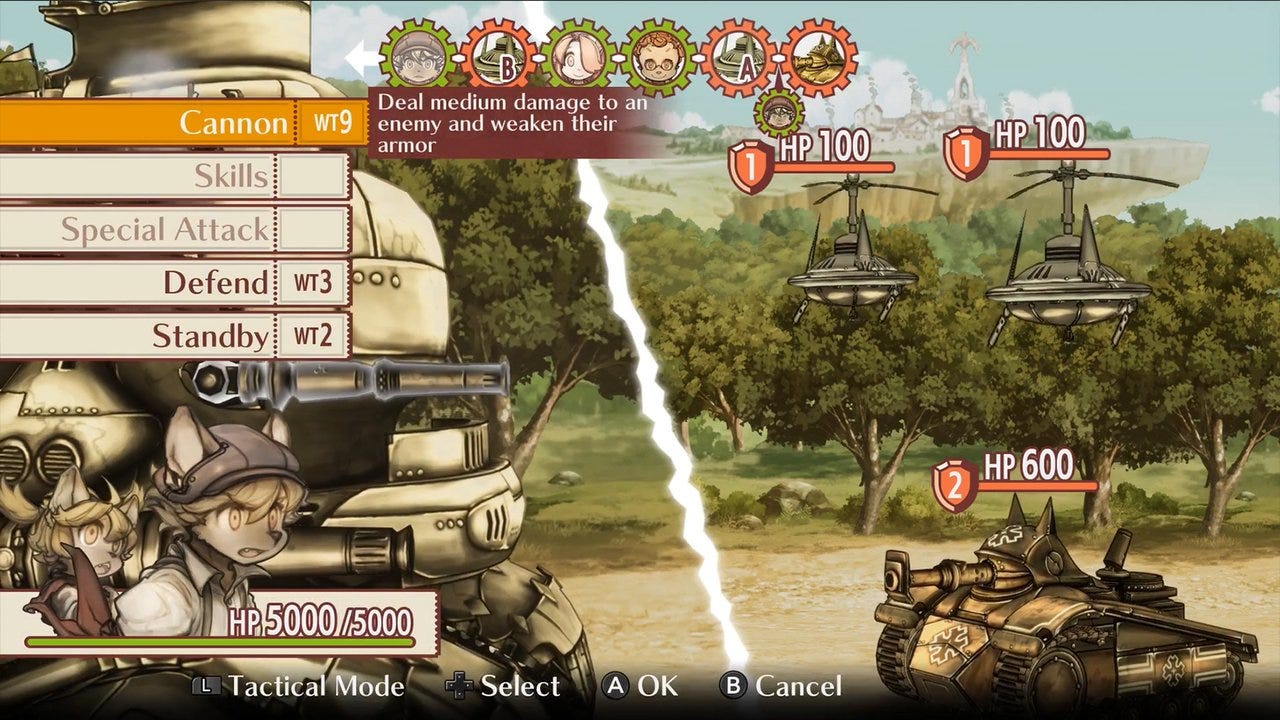

Gueritot ended up as a director in Fukuoka’s CyberConnect2 after establishing a good working relationship with Hiroshi Matsuyama, the vulcanic CC2 CEO who I still remember for always being in full cosplay attire during his European PR tours, working on the Little Tail Bronx’s latest entries, the Fuga: Melodies of Steel games, even if he ended up leaving CyberConnect 2 before the third game’s release.

French developers’ fascination with JRPGs featuring so-called anthro characters didn’t stop with Shiness or Gueritot’s Fukuoka adventures, but continued later on with a completely different game, strongly based on Breath of Fire, turn based RPG Terra Memoria (2024). Developed by Occitanian team La Moutarde, led by director Francois Bertrand, this peculiar game made a great impression of PS1 and Saturn isometric RPGs from an aesthetic point of view, not to mention how it sported a good balance of seriousness and humor, a robust (if almost completely optional) town building element influenced by Dark Cloud and a nice conditional turn based combat system whose rather imaginative mechanics ended up being noticeably hampered by its lack of challenge.

-AN IDEAL CONNECTION

Gueritot wasn’t the only Frenchman active in the Japanese videogame industry, of course: in the mid ‘10s, for instance, I had a chance to interview Damien Urvois, at the time working as part of Idea Factory’s PR staff during the pivotal years which saw IF establishing their own Western publishing arm, Idea Factory International, with Compile Heart’s titles carving out their own little niche in the low-budget JRPG space, especially on PS3 and PSVita.

Later on, while he was still working at Compile Heart, Urvois ended up being one of the founders, alongside Julien Bourgeois, of a new studio based in Paris, Artisan Studios, whose first project was actually a collaboration with Idea Factory itself, Super Neptunia RPG, a 2018 Hyperdimension Neptunia spinoff heavily based on tri-Ace’s Valkyrie Profile, showing yet again France’s fascination with side-scrolling JRPGs, both of the action and turn based variety. Interestingly, even if just on a JRPG-history level, Idea Factory had already been inspired by Valkyrie Profile’s combat for a number of other titles, from the small-scale sequences of Generation of Chaos (the first, unlocalized game in the series back on PS2, not to be confused with the fourth entry, brought to the West on PSP as Generation of Chaos) to Compile Heart’s PS3 crossover, Cross Edge.

This first effort acted as the foundation for their later game, Astria Ascending (2021), developed when the team had moved its studio to Canada, in Quebec City. Like with Monster Boy, Astria Ascending could be called a proper Franco-Japanese (or Quebecoise-Japanese, on a purely geographical level) effort since its director, Julien Bourgeois, recruited Hitoshi Sakimoto as composer and Kazushige Nojima as scenario writer, even if the game unfortunately didn’t make a splash since the game ended up facing a number of criticism despite its rather appealing 2D art direction.

After relocating yet again, this time back to France, in Montpellier (likely trying to chase the best fiscal and economical incentives between Canada and France, two nations already at the forefront in that regard), Artisan Studio started developing their third main title, Lost Hellden, even if unfortunately they didn’t manage to secure any meaningful publisher support and the company ended up filing for administration in December 2024 after running out of funding, with the future of Lost Hellden, and Artisan Studio itself, still pending.

-AT THE EDGE OF MONTPELLIER

Before seeing Artisan Studio’s last stand, Montpellier was already a very relevant city for French videogame development, housing one of Ubisoft’s French teams and yet another small company focused on Japanese-inspired RPGs, Midgar Studio.

Created around 2014 by a team led by Guillaume Veer, Midgar Studio didn’t try to pursue 2D or isometric Japanese-inspired RPGs, as most of the developers discussed so far did, but with its first effort, Edge of Eternity (not to be confused with End of Eternity, the Japanese title of tri-Ace’s Resonance of Fate), rather tried to build a full fledged 3D open world game, having to cope with a rather small budget and the size of their own company, which at its peak still had around fifteen employees. This is likely why they had to launch a 2015 Kickstarter campaign, which ended up being quite successful and allowed them to continue developing the game until its 2021 release, also securing the support of publisher Dear Villagers.

Veer and his team mentioned the inspirations behind their effort, showing a remarkable amount of variety: while Xenoblade Chronicles was unsurprisingly a huge influence on their open world design, seeing Legend of Kartia as one of their sources for character development made me smile back then, and Grandia being mentioned as one of the reasons behind their pivot to an ATB combat system (albeit with a number of tactical elements) was also interesting, if not really unexpected given its popularity among European JRPG fans active in the mid ‘90s. As with a number of other titles we’ve mentioned so far, Edge of Eternity also managed to secure some Japanese support for its development, or for its soundtrack in this instance, with industry legend Yasunori Mitsuda working alongside Midgar’s own Cedric Menendez.

Then again, while Edge of Eternity ended up being fairly successful regardless of its rather muted critical reception, with Nacon absorbing Midgar Studio allowing them to start working on a new project, Edge of Memories, it will be another 3D, turn based French RPG, also developed in Montpellier, that will end up popularizing this space to a degree that other developers would have never thought possible, both on a commercial and critical level. We’re speaking, of course, of Sandfall’s Clair Obscur.

-HEROES OF MIGHT AND LUMIERE

Montpellier will see yet another very relevant RPG-related development soon after. Considering how Ubisoft Montreal’s Child of Light has been one of the first French Japanese-style RPGs back in the early ‘10s, it’s perhaps fitting that the last chapter of this retrospective also starts with Ubisoft which, as we recalled, ended up acquiring the Might and Magic franchise from California’s New World Computing.

While we already covered how they tried to revitalize the main series, first with Arkane’s Dark Messiah, then with Might and Magic X, a Franco-German production mostly carried out by the Hessian team Limbic, its tactical spinoff franchise, Heroes of Might and Magic, also had a number of Ubisoft-published releases, mostly outsourced to different developers while retaining a core team of French staffers overseeing franchise continuity, including for the imaginative Might and Magic: Clash of Heroes, which briefly took the series in a new direction with a Japanese-style art direction and its unique mix of tactical and puzzle elements.

It was in this role, during Might and Magic: Heroes VII’s PC development back in 2015, that a young developer, Guillaume Broche, had his debut in videogame RPG development, after a number of previous experiences at Microsoft and Ubisoft itself. Despite being involved in a number of other AAA projects in different genres, Broche, a bit like Gueritot, was another Frenchman mostly fascinated with RPGs, especially Japanese ones, and, unlike Ubisoft Montreal’s Plourde, he felt he wouldn’t be able to make his own pitch and gain a proper directorial role for a game in that genre until much later, which understandably frustrated him.

-DEMAIN VIENDRA

This situation was the main reason behind Broche leaving Ubisoft in 2020, alongside his friend and co-developer Tom Guillermin, in order to create a new team, Montpellier-based Sandfall Interactive, where they could pursue their own unique concept, the title that will later become Clair Obscur: Expedition 33. While the game ended up using a lot of outsourced help during the second half of its development, the core team was always rather small, initially supported by a small grant from Epic (likely due to the game being developed on Unreal Engine 5) and by some national and regional funding from France’s own initiatives in support of local videogame development.

For obvious reasons, Sandfall’s first goal was producing a vertical slice for Cologne’s GDC, where they were able to impress publisher Kepler Interactive in order to gain most of the funding required for the project. The Broche family, involved in real estate and finance with a number of companies operating in France, may also have supported Sandfall Interactive’s effort in a number of ways, but I haven’t been able to independently verify this has actually been the case.

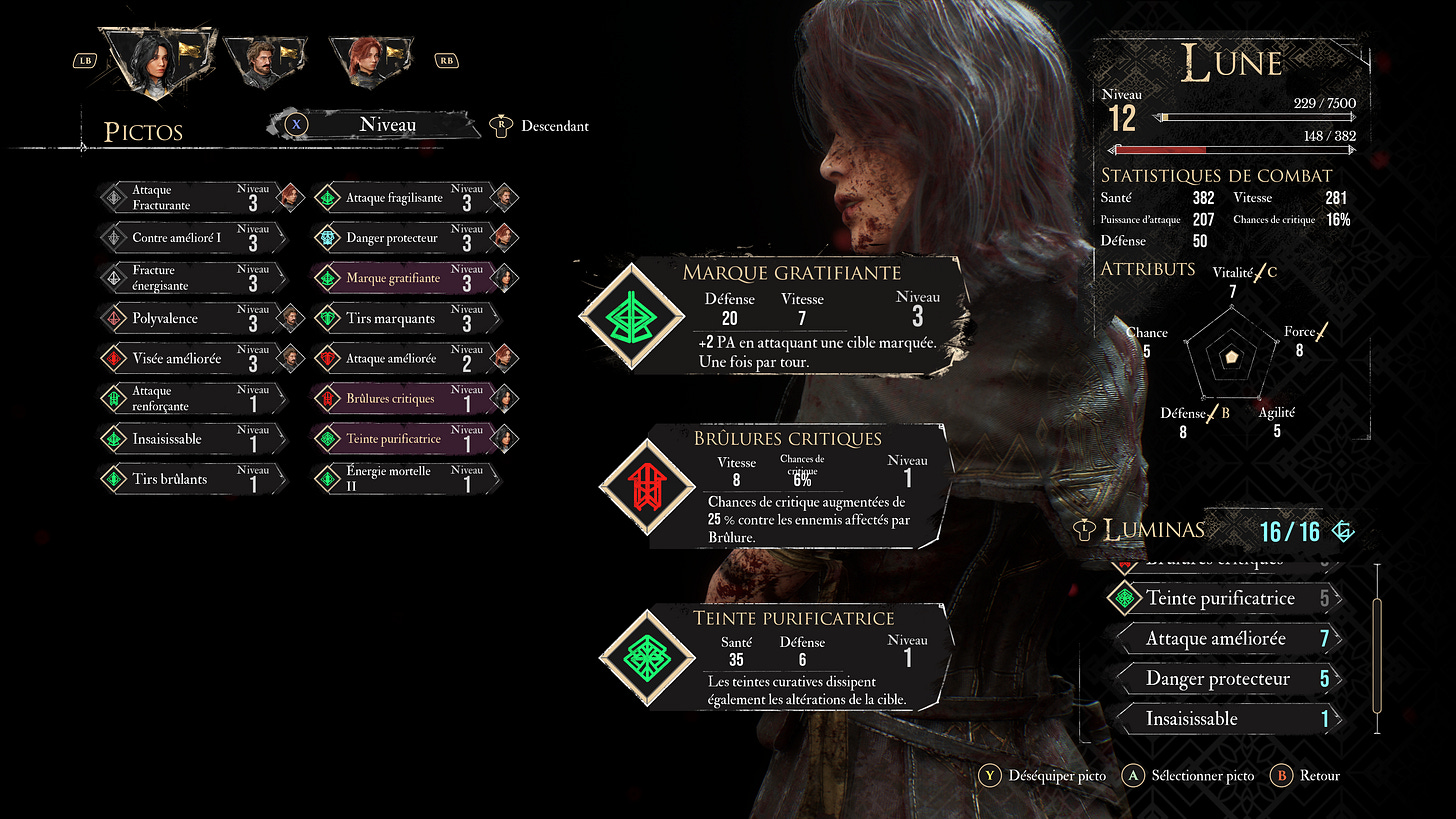

Clair Obscur’s concept, originally created by Broche himself, was later greatly expanded by Jennifer Svedberg-Yen, initially recruited as a dub actor for the game’s demo and soon repurposed as the game’s lead writer. Its art director, Nicholas Maxson-Francombe, was able to craft an unique aesthetic, mixing some realistic features influenced by France’s own Belle Epoque aesthetic with an heavy emphasis on surrealism, chromatic saturation and stylization without going the way of cartoon or Japanese-inspired aesthetics. Then again, Clair Obscur’s game design does feature a large variety of inspirations from a long list of Japanese RPGs.

While its pacing is reminiscent of Final Fantasy X and XIII, with the heroes’ titular expedition being stranded in an hostile land while trying to stop the mysterious Paintress before her Gommage deletes yet another generation, without much down time or urban areas to explore, the game also offers a proper overworld map full of optional areas, more in line with something like Blue Dragon or Ni no Kuni, while its tone is heavily reminiscent of Yoko Taro’s Nier or Yoshiki Okamoto’s Folklore and its dungeon design is actually inspired by From Software’s Souls franchise, including the game’s checkpoint system, based on flags rather than campsites (though camping in the world map is still a thing, even if it’s more like, say, Breath of Fire III), its attribute-based weapon scaling or its rechargeable consummables.

Then again, Clair Obscur’s turn based combat system is heavily based on timed button presses, whether for maximizing the damage ouput of a variety of skills, a bit like in Shadow Hearts or Lost Odyssey, or especially for defending, with a number of different defensive options depending on the pattern of the enemy attacks (evading, jumping and two kind of parries) that immediately reminded me of Cattle Call’s Tsugunai: Atonement on PS2.

There are also quite obvious thematic and narrative callbacks to a variety of other JRPGs that I will refrain mentioning because they would spoil some of Clair Obscur’s late narrative twists but, by now, it should be obvious that this game, even more so than previous French Japanese-inspired RPGs, is a love letter to JRPGs and their history, showing a remarkable ability to mix very different stilistical, narrative and gameplay traits into a cohesive and coherent opus while making them part of its own identity, without ever feeling like a random mishmash.

Another part of Clair Obscur’s identity is obviously its soundtrack that, rather than going for collaborations with famous Japanese authors, was composed by yet another fresh French developer directly scouted by Broche on a web forum in early 2020, Lorien Testard, who was able to produce a truly gigantic amount of remarkable and moody tracks, also thanks to the work of vocal director Alice Duport-Percier, with Studio Monaca’s work on the Drakengard and Nier franchise as a likely, sometimes even rather obvious, inspiration in the JRPG space, alongside plenty of others from a variety of sources and musical genres.

Due to its unique aesthetic and clever marketing, Clair Obscur ended up generating quite a bit of hype among RPG and JRPG fans well before it was out, but its critical reception was still way better than anyone could have realistically expected given the previous efforts in the Japanese-style Western developer RPG space, with its Open Critic metascore quickly rocketing to 92 and its sales soon surpassing three million copies sold. Even French President Macron, despite some very controversial opinion on the videogame medium shared just a few years before, felt he had to congratulate Sandfall for contributing to France’s image in the videogame space, renewing the Raffarin government’s old commitment to consider gaming as part of France’s core cultural output.

While the future still has to be written, including Sandfall’s future efforts, it’s easy to imagine how Clair Obscur’s success could end up revitalizing France’s already thriving RPG development scene, both in the Western-style and Japanese-inspired varieties, giving more space to upcoming releases like Spiders’ Greedfall 2, Tactical Adventure’s Solasta 2 or Midgar’s Edge of Memories while likely inspiring a new group of developers to delve into the RPG space while celebrating Japanese RPG design and themes, a trend that could hopefully end up affecting a number of countries like Germany, Italy, Spain or Poland where this kind of title has never been fully pursued by local teams and make France’s unique take on RPG development an Europe-wide phenomenon.