In the first part of this piece, we discussed France’s early start in videogame RPG development, with an incredibly rich scene already established in the late ‘80s, mixing titles inspired by worldwide hits such as Wizardry, Ultima and Might Magic with some unique adventure game experiments, which, as it happened in other regions, sometimes ended up mixing with interesting results.

That was also the age where the first mixup between French and Japanese RPG development materialized with Drakkhen and its complex history of ports and sequels, ending up with the lull of the early ‘90s in terms of French RPGs, despite a number of noticeable efforts like the Ishar series, Darkstone and Hexplore, and the fallout of the Dot Com bundle claiming the life of a number of storied developers before the Chirac-Raffaring administration started its ambitious policy of promoting French videogame development, both on a fiscal and cultural level, that is still alive and kicking to this day.

-RESILIENCE AFTER THE CRASH

Despite the Raffarin administration helping the French videogame industry to avoid a much larger disruption, by the end of 2004 a number of its key players had been swallowed by the crisis and, while many of the involved talents ended up resurfacing in different contexts, like we saw with Silmarils’ Rocques brothers, a number of other developers that didn’t participate in France’s budding RPG scene during the ‘80s and ‘90s took center stage in leading the new decade of French RPG efforts in the ‘00s, while also enjoying the relationships with international and regional publishers that allowed French videogames to be distributed worldwide and swiftly localized in English, something French developers still struggled to achieve just a decade before.

As we will see, compared with the previous two decades, French RPG development will experience a growing split between its Western-inspired output, which will end up mixing French and foreign teams in a number of ways while following gameplay and aesthetic trends compatible with American RPGs, and Japanese-inspired ones, which emerged in the late ‘00s due not only to the huge popularity of all manners of Japanese entertainment in France, but also due to the growing attempt by the French videogame industry to work in tandem with its animation industry, with the first few efforts actually emerging in the MMORPG space.

Those two spaces will actually end up progressing in parallel, mostly without interacting too much, which is why I choose to discuss them separately, with the second part of this retrospective focusing on the first, Western-adjacent strand of French RPGs, following a number of major players like Arkane, Spiders, Cyanide and, obviously, Ubisoft itself.

-AN ARKANE UNDERWORLD

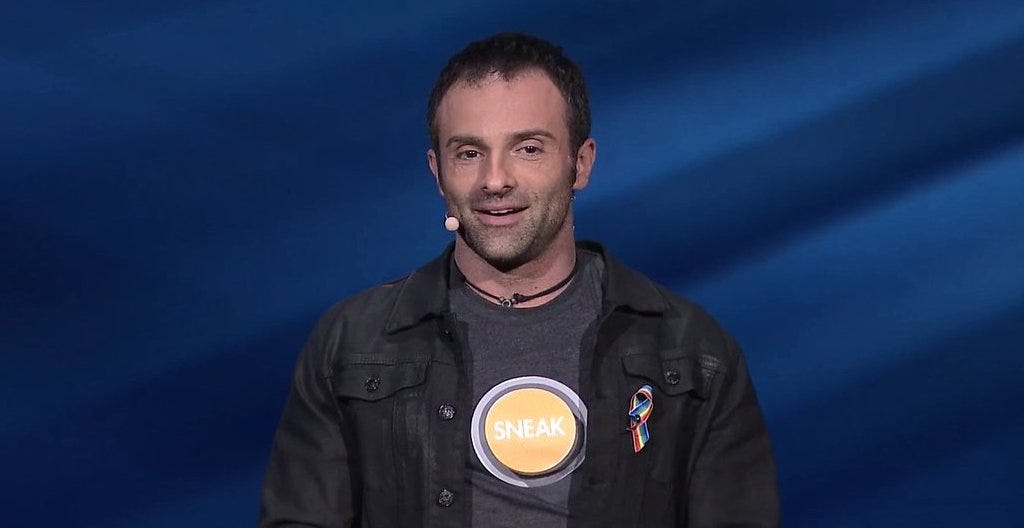

Discussing the post-Dot Com Western-style French RPG scene, one can’t really ignore the outsized impact of Raphael Colantonio. Born in 1971, Colantonio was part of a younger generation compared to most of the leading figures in the first wave of French RPGs, being just a child when Wizardry was brought to France as Sorcellerie or when the likes of Remy Gosselin, Matthias Wystrach or Marc Cecchi pioneered French RPGs with their first efforts, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t incredibly passionate and competent regarding the genre’s identity and history: when he was just eighteen, for instance, he took part in an Electronic Arts contest strongly based on the knowledge of Origin System’s Ultima series, which would jumpstart his career in the newly founded French EA branch, where he ended up focusing exactly on the localization of Origin System’s lineup. Later on, he felt Electronic Arts was pivoting too much on sports game, a genre he wasn’t interested in, and, after a brief stint at Infogrames, in 2000 he founded Lyon-based Arkane Studios.

Due to Colantonio’s skills in terms of leadership and game design, Arkane was able to assess itself with its very first title, Arx Fatalis, a first person action dungeon crawling RPG with magical glyph drawing via mouse movements which was heavily inspired by Paul Neurath’s Ultima Underworld series (an inspiration also shared by From Software for their King’s Field and Shadow Tower series, in the Japanese RPG space), which shouldn’t come as a surprise considering Colantonio had a decade to familiarize himself with everything related to Ultima, not just the Garriot-developed entries but also this very relevant spin-off series.

In fact, likely trying to leverage his previous work connections with EA, Colantonio initially hoped his new project could be marketed as Ultima Underworld III, going so far as to secure Neurath’s benevolence in this regard, but ultimately had to desist due to Electronic Arts’ rather unamenable stance on the matter, not only related to royalties issues but also to the control they wanted to assert on the game itself. In 2002, when the French videogame industry was failing left and right, it seemed Arx Fatalis could end up being cancelled, with one of its publishers going bankrupt and Arkane itself being in a very difficult position, until the game was thankfully rescued by Austrian publisher JoWood.

In the end, though, its lack or marketing and it being released just a few months after Bethesda’s landmark Morrowind entry in the The Elder Scrolls franchise made Arx Fatalis a darling for genre savants but also a fairly unsuccessful release from a purely commercial standpoint and, even if Colantonio originally wanted to develop an Arx Fatalis 2, possibly on Valve’s Source engine, things didn’t pan out for the same reasons that had plagued the original’s last development stretch, the lack of a reliable publishing partner that could help Arkane work without being consantly worried that their development efforts may come to an unforeseen halt.

-DARK MESSIAH OF HACK AND SLASH

Then again, Colantonio and his team’s prowess with first-person RPG combat and interactions were duly noted by Ubisoft, which in 2003 had just acquired from the dissolving 3DO Company the rights to a storied American RPG series, Might and Magic, previously developed by the legendary Jon Van Caneghem’s California-based New World Computing, another sad casualty of the financial downturn after it had been acquired by 3DO itself eight years before.

Thinking they had to modernize Might and Magic’s admittedly old-fashioned identity, Ubisoft tasked Arkane with developing an innovative spin-off, Dark Messiah of Might and Magic (2006), developed on Source engine, whose bold attempt at mixing action RPG with first person dynamic combat went much further compared with Ultima Underworld and Arx Fatalis itself, directly challenging Bethesda’s Battlespire, Redguard and Morrowind while also taking more than a page from proper first-person shooters, including fantasy renditions like Heretic and Hexen.

Dark Messiah, far from being a mindless slasher, gave a lot of emphasis not just to the player’s builds for Sareth, the game’s hero, with stealth mostly being as viable as magic or melee, but also to the interactions of its in-game physics in terms of environments and varied enemy tactics and behaviors, not to mention gritty combat that allowed for enemy dismemberment (a feature also touted by Treyarch’s third person Die by the Sword a few years before).

While the game featured dynamic storytelling that was, in some regards, ahead of its time regardless of its rather bland script, it undoubtedly lacked the depth previous Might and Magic games had purely in terms of exploration and customization, with a linear level-based structure and a single protagonist taking center stage in lieu of the series’ traditional party-wide efforts. Those issues, especially coupled with the expectations linked with a storied franchise such as Might and Magic, made Dark Messiah’s critical reception way more troubled than it would have been if it had developed as its own IP from the beginning, fostering the usual recurring arguments about it being part of the RPG genre at all due to how different it was.

Even then, the game proved to have a lasting appeal for genre fans purely because of its combat engine, securing a X360 port developed by an Ubisoft’s studio based in the fascinating Annecy, in Haute Savoie, and also being instrumental not just for Arkane’s own Dishonored, as we will see, but also for a number of other development efforts in the WRPG space in the next two decades, like the upcoming Alkahest, which even took back Dark Messiah’s trademark kicking. In turn, the most important franchise in this space, The Elder Scrolls, didn’t really take notice of Arkane’s work since it always relied on a more stats-based instead of physics-focused approach for its combat, which has led to decades of modding efforts trying to improve TES entries with traits similar to those introduced by Colantonio’s work.

As for the Might and Magic series (which, as we saw in the first part of this piece, had already influenced French RPGs with the Ishar series), after Dark Messiah it would unfortunately be kept as a mostly dormant IP by Ubisoft, making any talk about a Dark Messiah sequel moot, with a tenth numbered entry developed after a decades-long hiatus in 2014 by outsourcing Might and Magic X to Limbic Entertainment, a German company based in Hesse which actually had a number of French staffers involved in the project, like designer and writer Julien Pirou.

Limbic was also one of the developers Ubisoft tasked with working on the series’ storied tactical spinoff franchise, Heroes of Might and Magic, with its sixth entry developed alongside an Hungarian team and the seventh being handled solely by Limbic itself. But this, as we just saw, is a decidedly non-French story, publisher aside, much more suited to a retrospective about the German RPG scene (which well deserves its own retrospective, of course).

-SILVERFALL’S LEGACY - FROM MONTE CRISTO TO SPIDERS

While we will have more than a chance to return discussing Arkane in a bit, Colantonio’s company was far from the only one trying to reassess French RPGs after the first troubled years of the new millenium. In fact, while financial woes were the cause for all the bankruptcies we discussed before, Paris-based developer Monte Cristo (the Dumas reference was shared some years later by Korea’s Rhapsody of Zephyr) had been founded in 1995 by Jean-Marc De Fety and Jean-Cristoph Marquise, who had both built a very successful career in finance and immediately focused on developing finance-focused simulation games like the Wall Street series, which should explain why the company was able to survive the Dot Com crash without flinching.

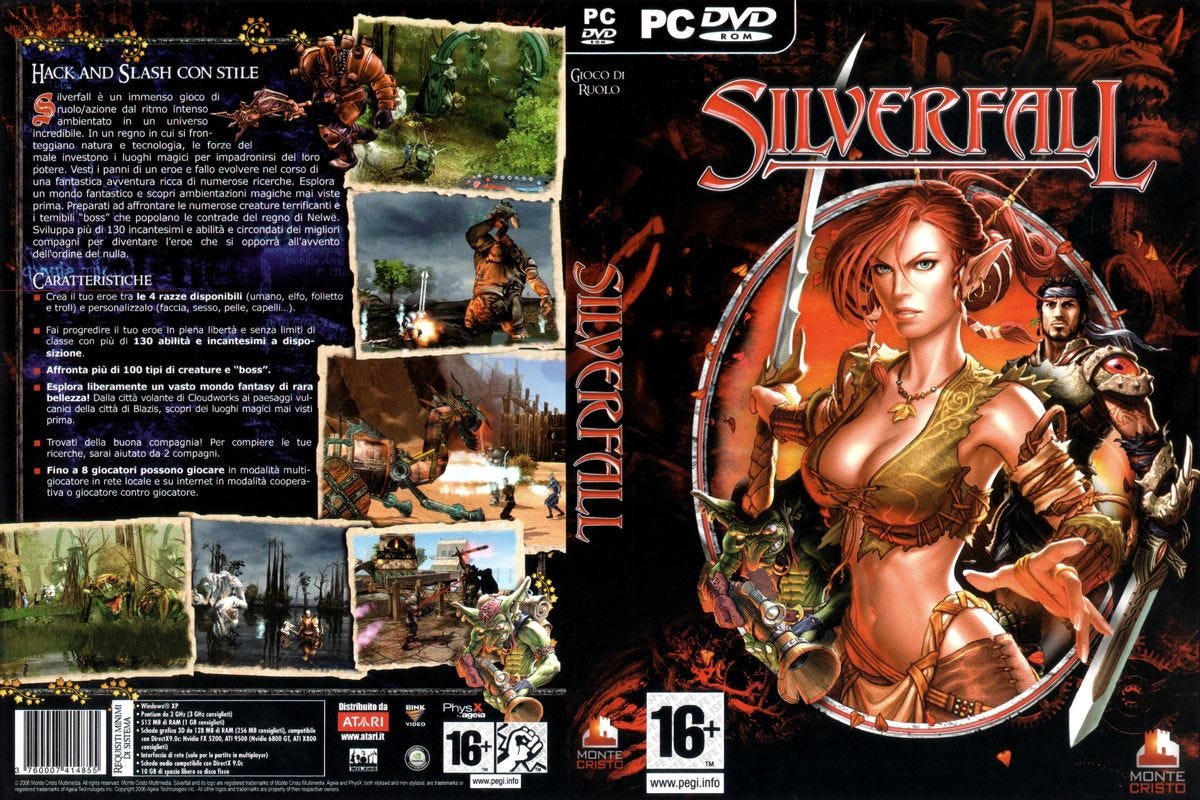

Some years later, with their lineup having extended to city building simulations and strategy games, Monte Cristo finally gave a chance to RPG development with Silverfall, a 2007 hack&slash action RPG in the vein of Diablo, Dungeon Siege or Titan Quest directed by a young and ambitious, developer, Jehanne Rousseau, that will become yet another rising star in the firmament of French RPGs.

While its party-based action formula wasn’t particularly innovative, Silverfall was one of the first 3D games to introduce a noticeably French twist in terms of its art direction, with cel-shaded models that gave it a comic-style feel, a space where Japan’s Level 5 was also working in that timeframe with Dark Cloud 2 on PS2, and a character design that, while still being firmly entrenched in Western sensibilities, also nodded to Japan, a trend that Rousseau would abandon soon after but that, as we will see in this retrospective’s third part, was becoming more common in French development, with Ankama’s MMORPGs as the biggest examples.

While Silverfall didn’t achieve widespread success, the team lead by Rousseau ended up being close-knit enough that, when Monte Cristo started having financial issues of its own in 2008, they formed their own team hoping to continue developing Western-style RPGs instead of the simulation games their previous company was known for (and which would soon bring about its demise, when Monte Cristo ended up closing down for good in 2010 after Cities XL’s poor sales).

The new team created by Rousseau and the other Silverfall developers was called Spiders and, like Monte Cristo, was also based in Paris. Since the beginning, Rousseau and her new company wanted to work in the RPG space, even if they abandoned the Diablo-like style Silverfall had while aiming at more narrative-driven experiences. Then again, it took them quite a while to return to RPGs: their first few efforts, likely trying to find their footing while building work relationships with publishers, were actually in the adventure game space, which, as we have seen in the first part of this retrospective, was always a core part of French gaming and was often mixed with its RPG output. They soon returned to their favorite genre with Faery: Legend of Avalon (2010), a fairy-themed turn based RPG which went back for a last time to Silverfall’s signature cel-shaded art style while including a number of unique quirks.

-OF ORCS AND THRONES

After Faery, Spiders went on to create Of Orcs and Men (October 2012), whose whole premise tried to subvert the usual relationship between those races in traditional fantasy settings while having the player help an orc warrior and his goblin sidekick in fighting the oppressive human Empire. This game was actually co-developed with another relevant French studio born at the turn of the century, Nanterre-based Cyanide games, created in 2000 by ex Ubisoft staffer Patrick Pilgersdorffer, which had already established a Canadian branch seven years later.

While working on Of Orcs and Men’s finishing touches, Cyanide had just released another self-developed RPG just four months before, Games of Thrones (June 2012), a peculiar action-RPG side story to Martin’s acclaimed ASoIAF novels which started its development before the serial adaptation made that license an incredibly popular mainstream hit among millions who had never even heard about the books. Cyanide’s Game of Thrones was also one of the first experiences in the videogame industry of Yoann Gueritot, back then working as a tester on QA, which we will meet again in the third part of this retrospective, seeing how he managed to become the director of a Japanese RPG series, CyberConnect 2’s Fuga: Melodies of Steel, just a decade later.

While Game of Thrones did have a number of issues, it still offered a rather interesting take on Westeros and a peculiar dramatic, almost theatrical flair that made it shine during its epilogue, and I felt it would have made a much bigger splash if its budget had allowed it to iron out its systems and presentation a bit more and if it had been released one or two years later, even more so considering how Game of Thrones’ popularity had basically no impact on the videogame scene outside of Telltale’s adventure series, leaving a large untapped potential that a competent RPG developer could have helped filling.

Then again, Cyanide took licensing as one of the major traits of its operation, with Games Workshop’s tabletop wargames as one of its mainstays, also explaining why Of Orcs and Men sounded suspiciously like a Warhammer (or Warcraft, which was itself originally born as a Warhammer-licensed game) parody at times. Actually, before tackling the Blood Bowl line with no less than three adaptations (one of Cyanide’s very first games, Chaos League, was a sort of off-brand take on this fantasy-themed American football), Cyanide had already adapted Rackam’s Confrontation miniature tabletop game and on Space Hulk, a Warhammer 40k side game based on small-scale combat between Space Marine Terminators and Tyranid Genestealers on destroyed spaceships.

In a way, despite not being a particularly successful title, Of Orcs and Men served as a turning point for both Spiders and Cyanide, with the first finding its way and defining some of its core traits, and the second going on to develop two prequels based on Styx, the goblin sidekick in the original game.

Then again, aside from its own issues, Of Orcs and Men was overshadowed even just in the context of French-developed RPGs by a vastly more successful game released just three days before it, on the 8th of October, a game called Dishonored.

-AN HONOURABLE DISHONOR - ARKANE AFTER DARK MESSIAH

While Spiders and Cyanide were growing in the late ‘00s, Colantonio’s Arkane was in full swing. In mid 2006, when the development of Dark Messiah was mostly finished and he was still working with Valve on Ravenholm, an Half Life 2 spin-off that would end up being cancelled soon after, Colantonio had established Arkane’s secondary studio in Austin, Texas, trying to expand his company’s development efforts.

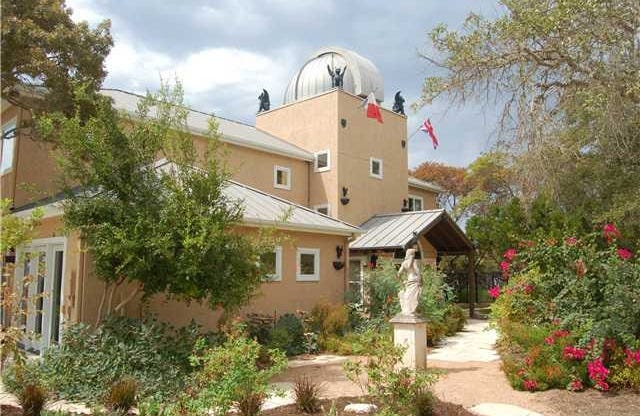

Anyone familiar with Western RPG history will immediately notice how Colantonio, himself a huge fan of Richard Garriott’s Ultima series and Origin System’s lineup, as we mentioned earlier, choose as the seat of his company’s American subsidiary the city where Garriott, Loubet and Roberts had crafted their storied franchises, ending up living there himself while he coordinated Arkane’s two branches.

While the next few years were very difficult for Arkane, with two cancelled projects forcing them to work as outsourced helpers for the Call of Duty and BioShock franchises, Arkane was finally able to find its footing around 2010 when it started developing Dishonored with Bethesda’s financial backing and, by then, Colantonio had recruited a very valuable developer, Harvey Smith, who himself started his career as a videogame developer in Austin, working on Ultima VIII at Origin System and on the first two Deus Ex games at Warren Spector’s Ion Storm.

When Colantonio and Smith met, the new Arkane was born, and Dishonored itself mixed Colantonio’s trademark focus on first-person action RPGs and reactive combat with Smith’s love for stealth gameplay and non-lethal progression options, which isn’t surprising considering how he tried pitching a new entry in the Thief series before leaving Ion Storm. Then again, when Bethesda’s Vaughn approached Arkane for discussing Dishonored’s original concept, which was based in Sengoku Japan, it was good old Arx Fatalis influencing him in thinking the French company was the perfect fit for the game they envisioned.

Dishonored was able to combine those unique traits with a number of RPG elements, a character design formed upon decidedly French stylized traits instead of pure realism and an incredibly fascinating steampunk insular setting reminiscent of eighteenth century London, a noticeable departure from Bethesda’s original Japanese setting which speaks volumes about the trust they had in Arkane, all brought to life by a budget that was able to realize the game’s vision and make it a standout success. In fact, while Arkane started developing Dishonored as a contracted developer, soon after they were actually acquired by Bethesda, a major change that still let them continue in their own way for a number of years.

Dishonored’s achievements were also possible thanks to the collaboration between Arkane’s Lyon and Austin studios, which worked together for this game, even if later on a number of theories will assign a major emphasis on the French team, which will indeed end up developing Dishonored 2 and its expansion without the involvement of the Austin branch. Then again, Smith himself would end up moving to France and direct the Lyon team’s efforts for Dishonored 2 (2016), showing how Arkane had became an international developer even when its divisions worked on different titles, like with Arkane Austin working on Prey, where Colantonio ended up working alongside CRPG legend Chris Avellone, acting as scenario writer.

Colantonio’s own departure from the studio he founded in mid 2017 (just one year after Richard Garriott’s legendary Britannia Mansion in Austin was demolished by its new owner) in a way closes the curtain on Arkane’s role in the context of this retrospective, with a bitter note a few years later when he bemoaned the closure of Arkane’s Austin studio, enacted by Microsoft after they acquired Zenimax and the team’s Redfall ended up as a disappointment.

Then again, soon after Colantonio’s Lyon would see the rise of a new RPG-oriented development studio, Tactical Adventures, which in 2021 would launch its first project, Solasta: Crown of the Magister, a tactical WRPG using the open source version of Dungeons & Dragons’ 5th Edition ruleset. The game’s director, Mathieu Girard, had already worked on a game we will have a chance to discuss in the third part of this article, Might and Magic: Clash of Heores and, with Solasta being a decent success with a sequel already in development, chances are Tactical Adventures will end up being another relevant player in the French RPG development scene.

-A MARTIAN DYSTOPIA - SPIDERS’ SCI-FI ESCAPADE

While Arkane was enjoying Dishonored’s reception, Spiders had just finished working on Of Orcs and Men, and Jehanne Rousseau probably felt she had to give her studio a more defined identity in terms of game design and narrative traits in order to have the team stand out in the crowded Western RPG scene. Focusing on a new setting of her own creation, Rousseau started working on a new, ambitious sci-fi Martian epic that brought Spiders back to autonomous action RPG development after their brief partnership with Cyanide.

While sci-fi settings were never incredibly popular among French RPG developers, after Philippe Ulrich’s Captain Blood in the late ‘80s and Cryo’s Dune adventure another developer, Streum On Studios, had tried to tackle that kind of setting with the wildly imaginative EYE Divine Cybermancy, mixing space opera, alien invasions and supernatural conspirations in the context of a first-person RPG with a robust emphasis on shooting, which later served as the basis for Streum On’s Games Workshop licensed titles, like Deathwing.

As for Spiders and Rousseau’s take on this genre, their post-terraforming depiction of a Mars who lost contact with Earth and ended up being rocked by countless conflicts between its city-states, not to mention regular humans, mutants and Technomancers, a new strand of humanity able to harness powerful energies while developing their own power structure, debuted with a small scale effort, Mars War Logs (2013), following the story of disgraced Technomancer Roy in a very linear way, despite also having some degree of freedom in terms of character relationships, choices and endings.

While its battle system and customization were fairly basic (with Rocksteady’s Batman Arkham games likely being one of the main inspirations behind its combat) and the game suffered from its noticeably low budget and the compromises it forced Spiders to make, it was still an interesting romp with a vibe not unlike so-called Eurojank titles, despite lacking the freedom and sandbox elements of Germany’s Piranha Bytes-developed titles or Eastern European RPGs like the STALKER series or Precursors.

While Mars War Logs was an interesting experiment, it was Technomancer (2016) that realized its sci-fi world’s full potential, albeit with the limits intrinsic to Spiders’ low budget, which this time had to cover for a more ambitious game while also sharing part of its initial development time with Bound by Flame (2014), a fantasy action RPG with a decidedly darker tone compared to their previous fantasy efforts.

Set after War Logs in a different corner of Mars, Technomancer offered a much larger world to explore, albeit still dividing it in separate areas rather than trying their luck with some sort of sandbox, while also dramatically expanding its lore and character interactions, including those Zachariah, a Technomancer from Abundance, will be able to recruit during his quest for truth.

Combat was also noticeably improved, both in terms of responsivity and variety, even if the game still has that noticeably janky air on a technical level, which also explains its rather modest sales.

Still, from a conceptual standpoint, Technomancer was a very important step for Spiders and Rousseau, showing their potential to both RPG fans and their own publisher, Paris-based Focus Entertainment, which would finally lead Rousseau and her developers to their own breakthrough with Greedfall some years later.

-UBISOFT’S RPG SHIFT

In the mid ‘10s, while Spiders was slowly progressing in its craft and Arkane was building on Dishonored’s success with the Lyon-developed sequel directed by Smith, the major player in France’s videogame industry (even if, as we will see, we could actually say Francophone videogame industry, given the major relevance of Canadian Quebecoise teams), Ubisoft, also started reassessing its role in the RPG space, which had been fairly minimalistic since their early efforts in the mid and late ‘80s with titles like Fer et Flamme and Anneau de Zengara.

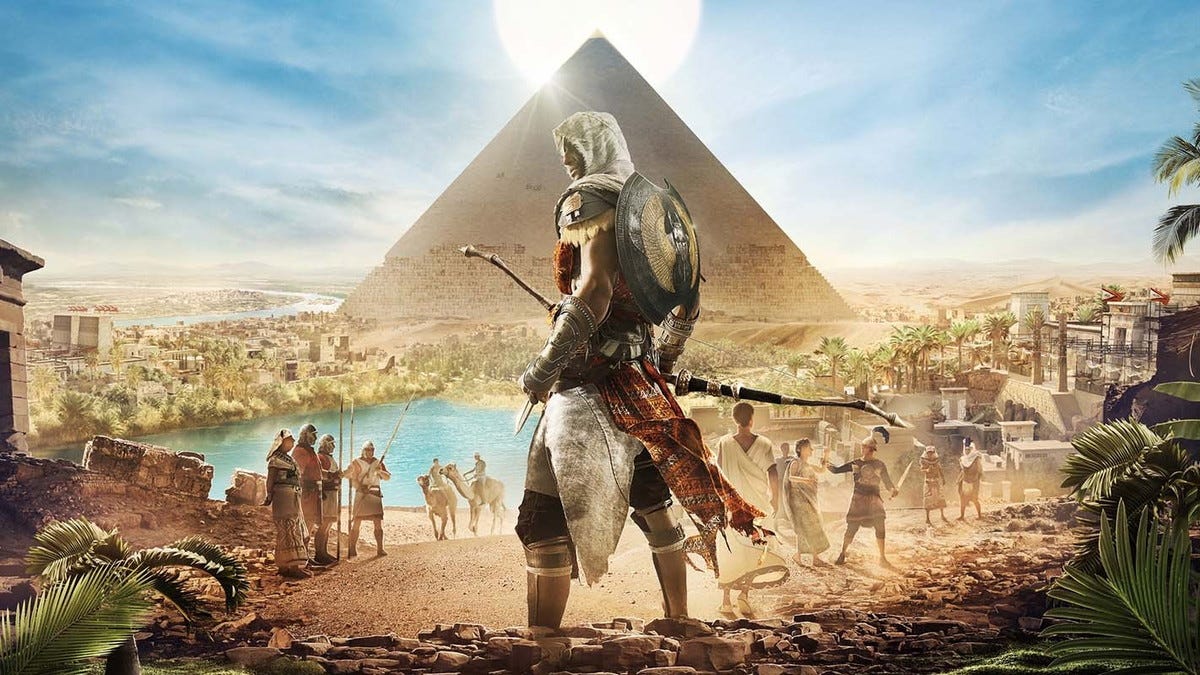

While the Assassin’s Creed franchise, created by Canadian designer Patrice Desilets in 2007, occasionally had some light RPG elements since its first entries despite its identity being firmly established as an action adventure franchise with an heavy emphasis on stealth and traversal, things started changing a bit with Unity (2014), mostly developed by Canadian studio Ubisoft Montreal but directed by Marc Albinet, a veteran French developer who started his rich career in the mis ‘80s after studying at Lyon and worked on franchises such as Little Big Adventure and Alone in the Dark. Albinet wanted Arno, the Parisian protagonist of AC Unity, set during the troubled times of the French Revolution, to feel like a more customizable hero, introducing skill trees to a series which always sported more linear character growth, if any.

Albinet’s choice, likely extensively discussed with other key figures at Ubisoft in order to make Unity a fresher experience for both newcomers and series veterans, ended up having a huge impact on Assassin’s Creed’s development vector in the next decade.

While Albinet left Ubisoft soon after alongside his co-director Amancio, Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, set in Victorian London and developed by Ubisoft Quebec, went even further with the RPG elements, introducing actual levelling alongside the skill trees, while 2017’s Assassin’s Creed Origins completed this transition, acting in a number of ways as a reboot with its Egyptian late Tolemaic setting mixed with mythological fantasy elements, stronger RPG systems (including dialogue options and choices with story consequences) and emphasis on explorations and questing, a direction that was shared by Odyssey and Valhalla, albeit with their different settings, all of which were developed by Ubisoft’s Quebecoise teams.

Interestingly, the only Assassin’s Creed game developed in France in the last decade, Ubisoft Bordeaux’s Mirage (2023), actually scaled down the RPG element by trying to return to the series’ roots, even if Quebec-developed Assassin’s Creed Shadows (2025) ended up reversing those changes by following the template of the three previous entries.

Those changes, of course part of a larger industry-wise trend, ended up having an impact on videogame development even outside Ubisoft’s output (where they also influenced the Far Cry franchise, aside from Assassin’s Creed), being one of the driving forces behind the popularization of RPG and open world elements in franchises that, until then, had used them more sparingly, not to mention how those features also ended up influencing monetization strategies and a number of game design and narrative choices. Ubisoft’s major emphasis on Quebec-based studios also had an impact on an already thriving development context (in the RPG space, it’s impossible not to mention Eidos Montreal’s Deus Ex games), which in the late ‘10s and early ‘20s, also saw the development of independent Quebecoise RPGs like Ninte Dots’ Outward.

-THE PLAGUE OF COLONIZATION

While Ubisoft was busy changing the identity of its main series, Spiders was also ready to step up with a game that will signify a major shift for this storied developer.

Greedfall, which started its development soon after Technomancer and was released in June 2021, was an action RPG set in a very imaginative and yet grounded fantasy take on the Age of Discovery, a kind of setting explored in the RPG space by Koei’s old Uncharted Waters series, Bethesda’s Redguard The Elder Scrolls spinoff, German Piranha Bytes’ Risen franchise and Chinese GY Games’ Sailing Era, among others.

Rousseau’s rendition focused on exploring the theme of colonization, with diplomat De Sardet navigating the complex political situation of the newly discovered land of Teer Fradee, where the nations of the mainland are quickly building a presence, exporting their old conflicts in the new world, while also having to deal with a diverse native population and with a number of secrets that will end up involving the world’s established religions, history and even Malichor, the plague that has been long plaguing that setting’s Old World.

Greedfall was a noticeable departure from everything Spiders had developed before, with a larger, more interesting and interactive world, a number of very interesting side characters, both recruitables and NPCs, and the hero’s own role making his mission very intriguing for those interested in political RPG opportunities. Even in terms of systems Greedfall offered a much tighter and responsive experience compared with Technomancer, with Mars War Logs’s clunkiness now a distant memory, and the various playstyles available to De Sardet, while often criticized for being a bit samey later on, did give the game a much needed amount of diversity in terms of builds.

Greedfall ended up selling two million copies, with the first million sold in less than one year, prompting the French authorities’ recognition of Rousseau’s talent and her role as an established figure in the country’s videogame development. In October 2021, she was awarded the medal of a knight of the National Order of Merit by the Ministry of Culture.

-ACCOLADES AND ADVENTURES

Given Greedfall’s emphasis on the theme of colonization, it was only fitting that the one that handled her this honor was none other than Muriel Tramis, herself a knight of the presitgious French Legion of Honor originally created by Napoleon I, who we already met in the first part of this retrospective as the Martinique-born author of Mewilo, one of the most pioneeristic efforts in early French adventure games back in the mid ‘80s.

Two years later, in 2023, Raphael Colantonio, which by then had long made his way out from Arkane, also received the French National Order of Merit and, outlining yet another time the links between RPG and adventure games in French videogame history, the one that handled him the medal was none other than Eric Chahi, the director of the legendary Amiga hit Another World.

Then again, while not directly linked to the subject pursued in this retrospective, the adventure games emerged in France during the mid ‘80s, including their RPG elements, were in some ways the precursors of the output of another famous National Order of Merit and Legion of Honor recipient, David De Gruttola (better known as David Cage), whose Paris-based studio Quantic Dream, heavily inspired by the idea of interactive movies, had often explored RPG-adjacent interactive narrative design spaces with titles like Fahrenheit, Heavy Rain, Beyond or Detroit: Become Human.

As for Spiders, with Greedfall 2, Greedfall’s prequel, now in early access pending its release later in 2025, Spiders is positioned as one of the main players in French RPG developments, even more so considering Arkane’s lack of RPG-focused projects after Dishonored 2 almost a decade ago and Cyanide and Streum On’s focus on licensed development.

Then again, Spiders, Cyanide and Streum On, alongside a number of other French RPG-focused teams like Kylotonn, which developed Cursed Crusade back in 2011, and some developers focused on Japanese-inspired efforts, like Midgar Studio and Dot Emu, do have something in common regarding their companies’ ultimate acquisition by Nacon, a large French publisher derived from old BigBen Interactive which has been building an outsized stable of studios in the last five years or so, while also ending up at the center of a controversy with developer Frogwares regarding the way they handled the Lovecraft-inspired adventure game The Sinking City.

While strongly associated with Japanese RPGs, even on a marketing level, one can hope that Clair Obscur’s recent success can end up helping other French RPG developers regardless of their choices in terms of systems and art direction by spotlighting a context that, so far had seen few interest from genre fans, even from a videogame history perspective. If Greedfall 2 also ends up being a success when it finally launches, the next few years could see a new wave of French RPG-related projects outlining that country’s diverse history with this genre, both on an indie and publisher level.

In the next, and last, part of this retrospective about French RPG history, we will see a completely different side of this development context in the post-Dot Com crash age, with a diverse roster of developers tackling MMORPGs and Japanese-inspired RPGs while still offering their own uniquely French take, with Clair Obscur as the current culmination of that trend.