Progenitor, Koei's forgotten PC98 space opera

Developer: Koei

Publisher: Koei

Producer: Yoichi Erikawa (credited as Eiji Fukuzawa, one of the aliases he used aside from the more famous Kou Shibusawa)

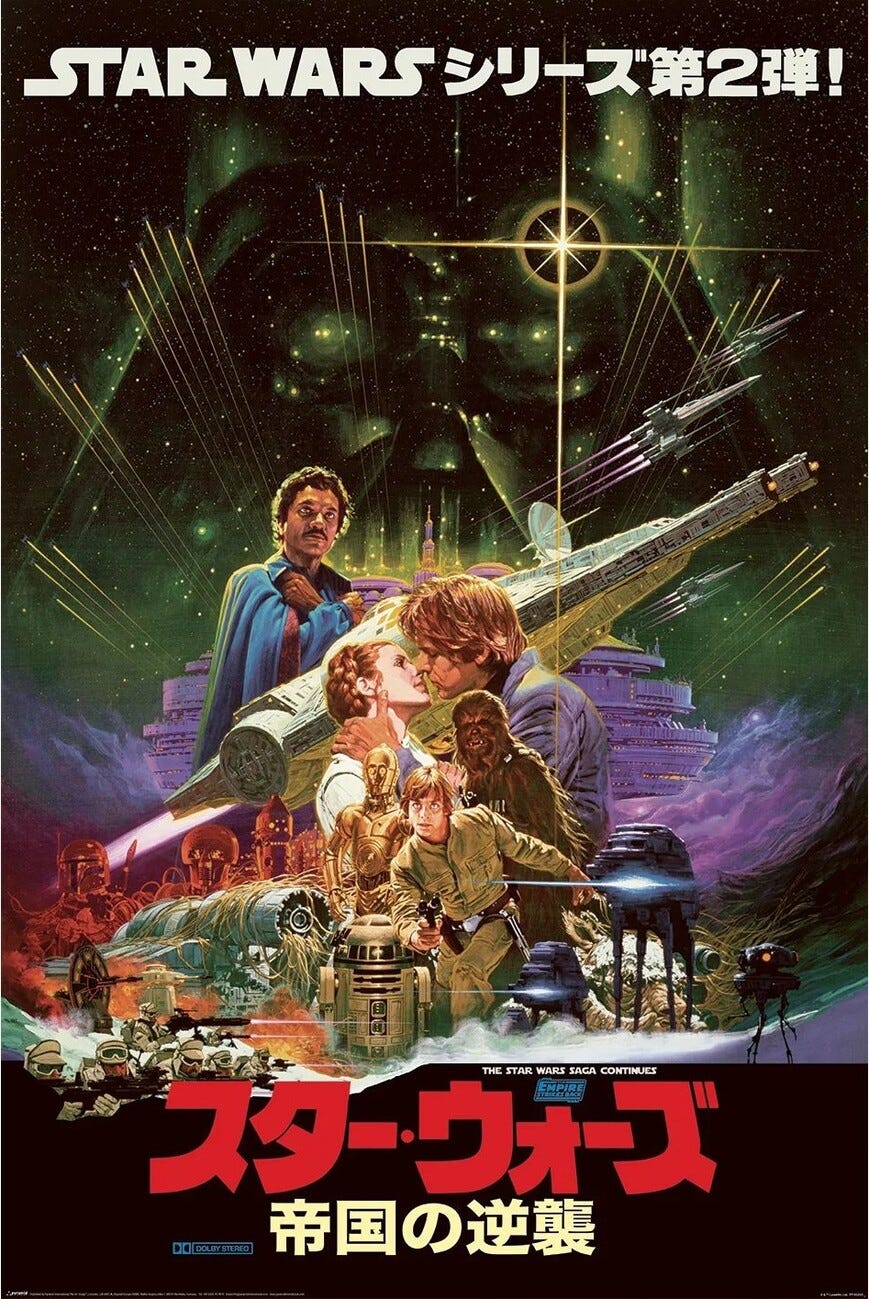

Art direction: Noriyoshi Ohrai (Uncharted Waters 1 and 2, Gemfire)

Country: Japan

Platform: NEC PC98

Release date: 1\10\1994

Status: researched in the last decade, with lots of roadblocks due to the scarcity of decent information available even from Japanese sources

Back when RPG subgenres were still fairly magmatic, Japanese developer and publisher Koei was at the forefront of experimenting new ways to mix simulation, adventure and RPG elements in a number of interesting ways, sometimes in the context of their own Rekoeition line. While most of those attempts were conveyed through their historical series, like Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Nobunaga’s Ambition and Uncharted Waters with their Late Han, Sengoku and Age of Discovery settings, their lineup also included mythological adaptations like Kojiki Gaiden’s early Japan and fantasy titles like Gemfire and Soldnerschild (which benefited from Ayami Kojima’s wonderful art direction). Koei also tried to bring its own innovative concepts to the sci-fi space with Progenitor, a lesser known title which ended up providing one of the very few space opera JRPGs alongside Robotrek, Infinite Space and the Cyber Knights and Xenosaga franchises, in a context where the sci-fantasy mix featured in series like Gdleen and Digan no Maseki, Cosmic Fantasy, Phantasy Star, Star Ocean and EXA_PICO has historically been more common.

Progenitor, released in October 1994 on NEC’s PC98, is probably one of the more elusive and less documented title by this otherwise renowned publisher, a fate that it unfortunately shares with a veritable army of incredibly interesting JRPGs released from the mid ‘80s to the late ‘90s on Japanese home PCs such as Sharp X68000, FM Towns, MSX2, PC88 and PC98 itself, with Artec’s Digan no Maseki, Right Stuff’s Libros de Chilam Balam, Enix’s Reichsritter, Gust’s Ares Ou no Monogatari and Kure’s Early Kingdom as some of those that have been able to fascinate me most over the years. While Koei actually released many of its titles on home PCs at first, most of them later ended up being ported to Famicom, Super Famicom or Mega Drive, making them not just more accessible in their home country, but also allowing for some early localization that helped to establish Koei outside Japan.

Unfortunately, Progenitor didn’t share the fate of Gemfire, Koei’s fantasy grand-strategy JRPG, or the Uncharted Waters line, and PC98 became its graveyard, possibly also because Koei president and Progenitor producer Yoichi Erikawa (here credited as Eiji Fuzukawa, but better known for his other alias, Kou Shibusawa) at the time was starting to restructure his own Rekoeition brand in order to focus on its more established franchises, instead of single entry games like this one.

Regardless, the game actually managed to retain some niche following among those Japanese players old enough to fondly remember the age of home PCs, and one running theory of mine is that Progenitor could have somewhat influenced some traits in what ended up being one of my favorite sci-fi JRPGs, Platinum and Nudemaker’s Infinite Space on Nintendo DS, which, aside from some obvious differences, in a number of ways could seem almost like an home PC game time-warped to 2009, even if I must stress that any connection between those titles is purely hypothetical and, researching Infinite Space’s developers, only a few even were in the age group which one could possibly associate with having played Progenitor, with director Hifumi Kouno interestingly being involved with an old-school adventure visual novel released in 1998 on PS1.

Be it as it may, after recently bemoaning the lack of an English fantranslation effort for Progenitor while discussing 46Okumen’s Appareden fantranslation, it dawned to me that it was hard for fantranslators, or anyone else for that matter, to get invested in a game that had basically no meaningful English coverage, with even Japanese sources being far from ideal in terms of providing unified, detailed information. Thus, I decided to do my part, as humble and unimportant as it may be, by trying to put together what little research I made over the years in order to introduce more people to this inspiring sci-fi JRPG.

Part of Progenitor’s charm, well before one can start researching and appreciating its narrative and gameplay, is surely due to its art direction, featuring a cover by late renowned artist Noriyoshi Ohrai, who, more than a decade before working on Progenitor, already had a strong sci-fi slant in his portfolio due to his work on Star Wars’ posters and promotional material. He also loved to portray historical figures and events, which explains his long-standing collaboration with Koei, which saw him illustrating a variety of titles in the Uncharted Waters, Nobunaga’s Ambition and Romance of the Three Kingdoms franchises, not to mention stand-alone titles like L’Empereur or Gemfire.

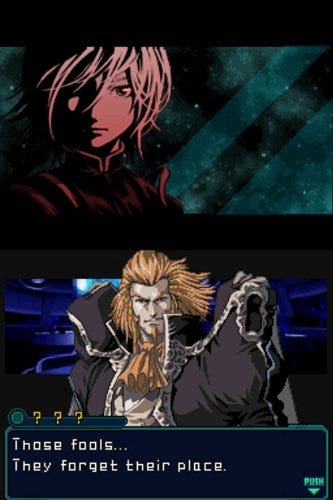

Then again, considering it’s very unlikely Ohrai actually worked in any meaningful way to coordinate the game’s own art direction, Progenitor’s unsung heroes on an aesthetic level are surely its sprite artists, which were able to build a complex and diverse galaxy with its own unique vibe and plenty of incredibly detailed backdrops, making it one of the most visually striking JRPGs in the already delightful home PC space. While those staffers have been sadly left uncredited everywhere, purely based on their style I think we can assume they were roughly the same developers who had previously worked on the Uncharted Waters titles, possibly with the addition of some new blood for tackling Progenitor’s full-screen location art and event CGs or, as we will see later, for the game’s unique proto-3D sequences.

It’s now time to delve a bit into Progenitor’s own setting and narrative. After a mysterious event known only as the Armageddon destroyed the old spacefaring civilization in Progenitor’s universe, three variants of the human race that had adapted to different biomes, the Humanas which retained old humanity’s physiology, the mysterious masked ones, called Onams, and the green-skinned Karapps, developed separately for thousands of years, slowly building back their cultures and technologies and finally meeting again when they managed to resume their journey to the stars. Obviously, this encounter was far from easy, with all manners of tensions escalating into a conflict that lasted for almost two centuries, when the three now-reunited branches of mankind finally agreed to a peace treaty and built a Space Federation to try regulating politics, war and trade among different planets and nations, with New Front as its center.

With all new powers come new regulations, and spacefarers who didn’t appreciate the Federation’s rule ended up turning into smugglers and pirates, with some of them forming a sort of association, called Rocka Bats (the game’s own romanization, as shown by its insignia during an early event in Shark’s office on planet Gastgar), intially acting as the spacefaring equivalent of a Robin Hood-esque free league, fighting both criminals and law enforcement while trying to keep the space frontier peaceful and free.

If the Rocka Bats were initially an idealistic group, formed by people of different races and nationalities trying to build an alternative to the Federation, soon their military and economical power made them the perfect springboard for the rise of the unsavory Gadem Goza, which, after becoming their leader, quickly harnessed their power and remolded them into a ruthless and feared space-syndicate.

Among the early Rock Bats, however, not everyone was interested to comply with this new autocratic vision: Clyde Fitzgerald, one of the group’s founders, alongside his son Kenny (a name that fans of tri-Ace’s Star Ocean sci-fantasy JRPG series will immediately associate with the franchise’s reccuring Earthling family line of Federation officers and spacefarers, a potential inspiration that unfortunately isn’t discussed anywhere), are growingly uneasy with Rocka Bats’ new identity and, when fellow captain Brad chose to target a civilian ship, El Dorado, just to kill a single Federation officer, Kenny finally starts losing faith in Rocka Bats.

After his father dies while coordinating a mysterious projects for the organization, Kenny also ends up at odds with the top brasses when one of his friend, female Humana Reggie, disappears with her cargo and is accused of theft by Scorpio, a Rocka Bats druglord.

After refurbishing his spacecraft from Venetoria planet’s Glame Inc., which amusingly (or not) uses AI to serve its customers, Kenny and his crew, including his old mentor, Margus, aristocratic Onam Lady J with her Carnival of Venice-style outfit and Karapp Gunther, depart to search for Reggie while musing to finally abandon the Rocka Bats, not knowing that destiny has a lot more in store for him than he knows, as hinted by the mysterious Memento Ring left to him by Clyde.

After recovering Reggie from the talons of Shark, a Rocka Bats planetary leader, they are ambushed by Scorpio’s fleet, who was waiting for Kenny to betray the organization and almost manage to eradicate them before they are able to flee to nearby planet Aquas. Having survived this battle, the game finally opens up, allowing the player to freely explore the galaxy while pursuing Kenny’s own story, with the Rocka Bats faction, the Federation, the fate of Clyde and the ancient spacefaring civilization and its ruins as some of the core themes.

Progenitor uses a permanent user interface setup in the right part of the screen, with Kenny’s portrait, main stats and resources (cargo capacity, fuel, money and energy) always available, while the actual game is rendered in the leftmost box, a rather typical arrangement for Japanese home PC (and early Windows) games, especially adventure titles and visual novels, immediately reminding me, among others, of Uncharted Waters’ PC88 original version, early Falcom games and YU-NO, Elf Corporation’s landmark visual novel, originally developed on PC98 and localized by a fantranslation effort a decade ago, before it was actually remade for current hardware.

Interestingly, as different as they may be in pretty much every other way, Progenitor and YU-NO also share an important plot point, with the protagonist’s father mysteriously disappearing while working on a nebulous project involving ancient ruins and mysteries that can reshape the world as we know it.

The game has plenty of different star systems (or Areas, as the game calls them), each with its own sets of planets, with quite a number of different ones already available right in the first thirty minutes. Each planet or space station (which have a lot in common with the ones seen in series like Legend of Galactic Heroes or early Gundam, one apparently even having the Side nomenclature) is shown as an unique city map, where you can select different locations with the usual point and click interactions. Different planets often have their own, unique areas, from government facilities to a late game casino where everyone must be masked, to Lady J’s delight.

Each area is rendered through an artwork with a variety of interactive elements, reminiscent of adventure games, whether they are shops, point of interest or NPCs to talk with. When you are finally ready to go for the stars, you can clik the button at the top of the city map and warp to the spacefaring interface. One of the lower buttons in the game’s UI brings up its own space map, where you can see routes between known planets: starting in Venetoria, where Kenny resides and meets his buddies in the Hellion Bar, the protagonist can soon reach a number of other planets, like Island, Gastgar, Aquas, Grassvale, Diaz or Kyana (those are just my romanizations, as I’m not aware of any official ones, in game or not).

Progenitor actually features two different space travel modes: regular interplanetary travel, which can be done even on a mere space shuttle, takes more time and is only possible within a star system or Area, while turbo-drive travel, which allows to travel to distant star system, consumes more fuel and is only available when using more advanced (and pricey) ships.

While most of the game is conveyed by beautiful sprite art, with boxed portraits and event CGs used depending on the event’s relevance, Progenitor was also fairly pioneeristic in introducing proto-3D models for its spaceships, a bit like with GameArt’s Silpheed or, with obvious hardware differences (even more so considering the Super FX Chip inside its cart), Argonaut and Nintendo’s Star Fox.

This is mostly related to Progenitor’s cutscenes, with a wide variety of ships and shuttles being portrayed in those 3D events right from the start, when captain Brad opens fire on the El Dorado to the dismay of Kenny and his crew. Of course none of those scenes are actually interactive, but it’s still fairly impressive for a game of its age, making even more obvious how Progenitor was a rather high budget production for Koei and, indeed, the Japanese home PC videogame industry’s standards.

Combat, presented much more traditionally, can occur both on land, with first-person shooting gallery sequences reminiscent of Snatcher and Policenauts handled by moving the cursor toward the enemies before they’re able to defeat Kenny, and obviously in space, where fleets are shown on opposite sides in turn based dogfights, with a variety of tactical options to engage depending on the weapons and type of ships available, even if the actual combat ends up being mostly automatic. Ship customization is obviously very important, with incredibly strong ships being available since the beginning and money being the main barrier.

Aside from the obvious differences in terms of settings, Progenitor has actually a lot in common with Uncharted Warters, with the core gameplay loop being heavily focused on commerce, exploration, resource management and slowly improving your own fleet in order to be able to face the growing threats of different kind of enemies, with Rocka Bats being the earliest enemy but far from the only one.

Speaking of factions, while the presence of three different human varieties made me think this sort of ethnic division would be one of the setting’s core elements, from what I’ve been able to piece together that side of the story seems to have been mostly solved with the old war before the Federation was founded, even if the game’s mysteries regarding the old civilization’s demise and the Armageddon event could shed some light on those points. Then again, one could also imagine Progenitor treating the differences between those groups the same way Koei’s Uncharted Waters series treated the differences between various cultures and States in the Age of Discovery, which, despite being very much relevant purely on an historical level, always played a secondary role compared to adventuring in the games themselves.

Even discoveries are still here, with Uncharted Waters’ landmarks being repurposed here as mysterious ruins linked with the game’s overarching mysteries. You can also buy mining rights from planetary government, accept bounties and hunt pirates or, if you want to undermine Kenny’s own character development, turn back to piracy and loot trading ships, even if apparently that can provoke a rather brutal response from both local and Federation space forces. Freeform, sandbox gameplay indeed is one of Progenitor’s (and Koei’s early hybrids) more appealing traits, something that could end up making it a cult hit with players invested in series such as Akitoshi Kawazu’s SaGa, or Koei’s own Uncharted Waters.

Same as in other Koei titles, like the Uncharted Waters and, a few years after Progenitor, Zill O’ll on PS1, plot progression seems to be linked with engaging with the world itself, with both the passage of time (shown in the upper right part of the UI) and acquiring money and resources apparently triggering new story events.

Compared to Uncharted Waters, which, since its first entry, offered multiple protagonists and kept improving the number and diversity of alternative scenarios as the series went on (a trend that was picked up by GY Games’ Sailing Era, a Chinese tribute to Koei’s storied franchise), with the noticeable exception of Daikoukai Jidai 3, Progenitor choose to focus on a stronger narrative, with a single plot thread developed in an incredibly expansive galaxy while balancing a robust campaign with the freeform gameplay loop Uncharted Waters introduced in its own Age of Discovery backdrop.

Indeed, while the wonderful Infinite Space could have unknowingly picked up some of Progenitor’s broader traits, it still offered a very different, somewhat simpler experience since it never tried to delve into its simulative and economic systems, meaning Progenitor still stands as a unique title in the sci-fi JRPG landscape, one that could have surely garnered a lot of interest from a variety of niche demographics if it had had a chance to shine outside of Japan, or if it was ported on more popular platforms. Then again, part of its charm is exactly due to its peculiar development and historical context, making it an unabashed representative of the unsung glories and ambitions of home PC JRPGs in a world that is still waiting to rediscover them.

With the Japanese home PC fantranslation scene being currently uplifted by the awesome work done by a variety of teams and people, one can hope the day will come when Progenitor, too, can be enjoyed by English speakers, bringing to light Koei’s own forgotten, incredibly interesting space opera.