Developer: Prime Games

Publisher: Prime Games

Director: Victor Atanasov

Composer: Cameron MacMillan

Source material and original writers: Dave Morris, Jamie Thomson

Genre: Gamebook RPG with turn based tactical combat

Progression: Completely sandbox, with a huge number of quests you can develop simultaneously while exploring the world and no ending to speak of

Developer’s Country: Bulgaria (USA for the original gamebooks)

Platform: PC

Release date: 26\5\2022, with the final DLC available in May 2024

Status: Completed on 20\1\2025 (since there’s no proper ending, I actually left the game after reaching maximum rank, exploring all the regions and doing most subquests)

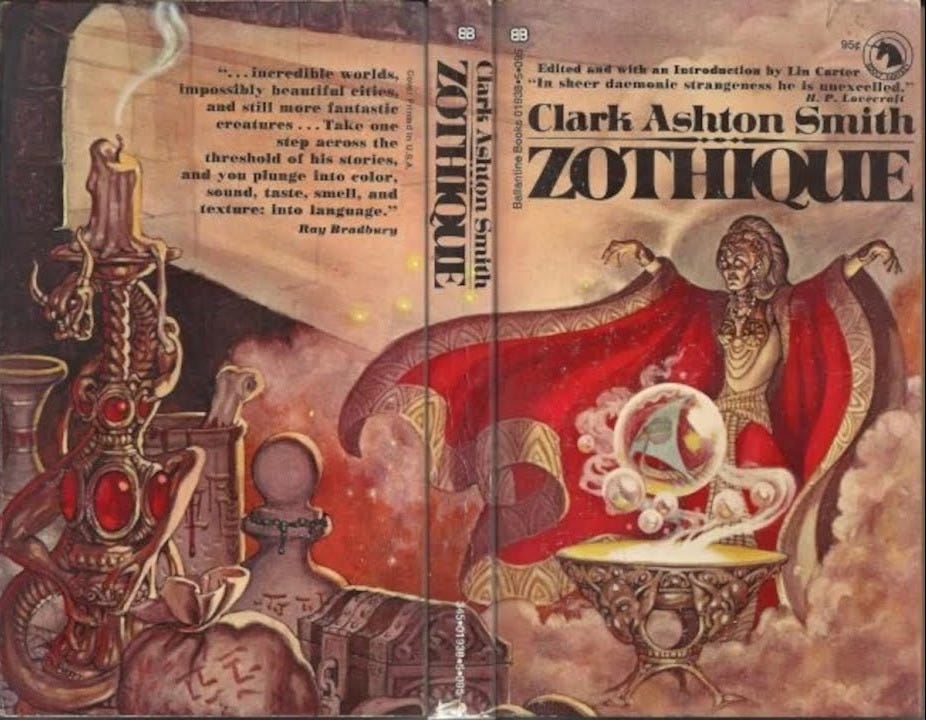

In the context of videogame RPGs, there are precious few options for those interested in experiencing the adventurous, fever dream-like feel of old sword and sorcery literature: be it Clark Ashton Smith’s Zothique, Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane Saga, Robert Howard’s Conan or Michael Moorcock’s Elric, Corum or Hawkmoon, those storied series haven’t really had a wide, long-standing thematic following among videogame developers (aside from a small number of exceptions, like A Sharp’s King of the Dragon Pass, based on the Glorantha setting, and a number of dungeon crawlers), possibly because the influence of D&D-themed sword and sorcery à la Dragonlance or Forgotten Realms, which was incredibly strong exactly when Western videogame RPGs started hitting their stride, ended up diluting some of their themes and unique quirks, even if some settings, like Greyhawk and Dark Sun, did have a bit more in common with them on a variety of levels.

While today’s dark fantasy literature surely does have a following in the videogame space, many of its core premises couldn’t be more distant from the old sword and sorcery vibes: Martin’s musings about historical realism, taxation and politics, or Sapkowski’s grittiness, while perfectly understandable in the context of their own works, can hardly mix with the hazy atmosphere of the dead temples of Zul-Bha-Sair in The Charnel God, with Elric’s deranged voyage on the Ship of Fate, or with Kane enacting his dark plans in the jungle ruins of inhuman Arellarti. There’s a mythical, otherwordly quality in older sword and sorcery novels that trascends their mere narrative and calls on their underlying archetypes as the hidden pillars of what they actually want to convey, something that I feel has been largely lost with the way fantasy literature has developed since then and that videogames have an even harder time to portray.

Happily, though, there are indeed ways for videogame RPG lovers to experience those feelings in their medium, at least partially, thanks to the adaptation of old Gamebooks, where the readers could act as the main character by crafting their own story while exploring the paragraphs depending on their choices and interacting with each book’s ruleset. This incredibly fascinating hybrid between single-player tabletop RPGs and novels, very popular a few decades ago with series such as Joe Dever’s Lone Wolf and Oberon the Wizard or Jackson and Livingstone’s Fighting Fantasy, mostly adhered to traditional sword and sorcery tenets in a variety of ways, offering single player RPG experiences with an heavy narrative emphasis right in the days where that subgenre wasn’t just extremely popular, but also still active.

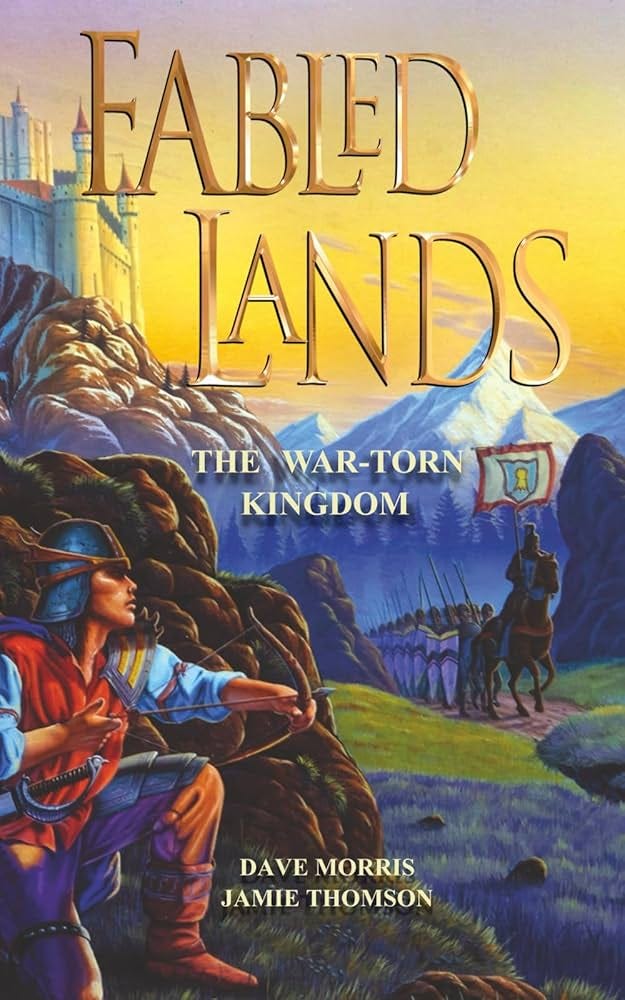

While Gamebooks have inspired a number of modern RPGs, like with theawesome Russian-developed The Life and Suffering of Sir Brante, there have also been efforts to repurpose the Gamebooks of old to the new digital context. In this, Dave Morris and Jamie Thomson (who also was the co-writer for some Fighting Fantasy books)’s Fabled Lands franchise, published between 1995 and 1996, is probably the best suited, because of its incredibly imaginative and experimental structure: while regular Gamebooks tried to tell a story, with series having a sequence of independent tales lived by the same or characters, often growing book by book, Fabled Lands opted for a completely different system, with each book associated to one of the regions of the lands of Harkuna and the player being able to travel between books, with paragraphs linking to different regions and an intricate system of keywords to keep track of the main quests undertaken by the hero, with the world often reacting to them in a variety of ways even in the most unpredictable contexts while pursuing a journey into a world of pure, unadultered sword and sorcery.

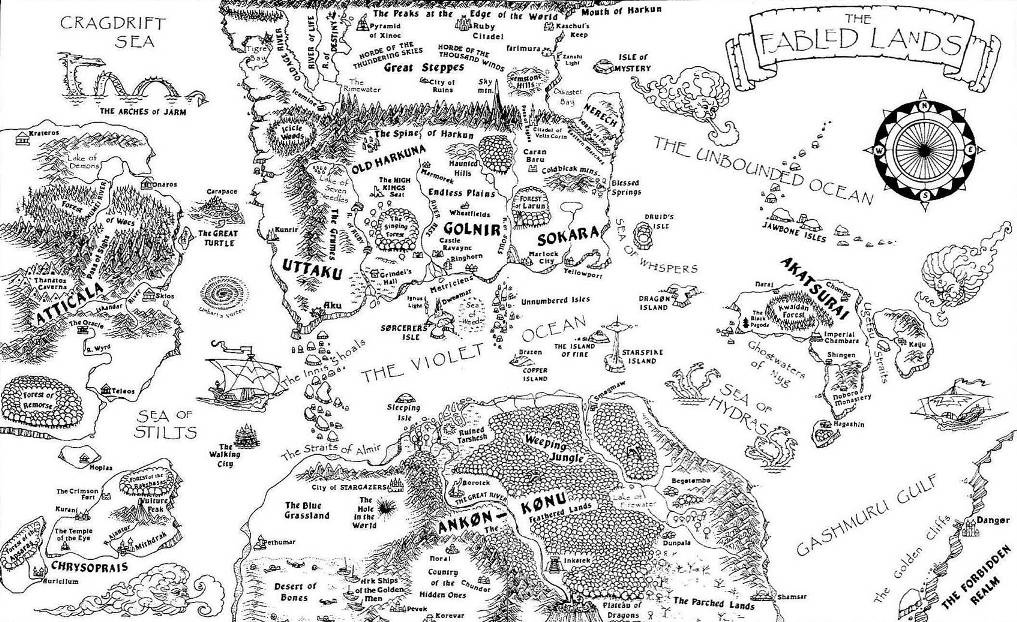

While originally in 1995 the series was only able to be published up until its sixth book, later a Kickstarter effort made it possible to finally complete and release the seventh, penned by Paul Gresty and set in the mysterious jungle of Ankon-Konu, even if there are still regions, like the western Atticala continent, that are left unexplored. Even if Gamebooks were extremely popular in my country, Fabled Lands unfortunately wasn’t published here back in the days, which means I was able to get a hold of the series only much later but, even decades after its release, it’s still a groundbreaking experience, showing how versatile and rich Gamebooks can get while used in innovative ways and . In fact, in many ways, one could consider them as a sort of bridge between Gamebooks and sandbox videogame RPGs, with Dave Morris’ following series, Vulcanverse, going even further by providing an actual ending, which Fabled Lands had avoided in order to preserve its open-endedness.

It isn’t so surprising, then, that Fabled Lands ended up getting its own videogame adaptation which, in this instance, is actually a literal adaptation rather than a reworking of its source material, as it often happens. At first, in the early ‘00s, Fabled Lands was adapted in Java as Java Fabled Lands, an application lovingly developed by Jon Mann, who actually acted with the full consent of the authors and of the original artist who worked on the book’s illustration, Russ Nicholson, making the series available at a time when it was becoming hard to find and showing how compatible it actually was with a digital fruition.

Then, after the 2019 Kickstarter reignited the interest in the franchise and made it possible to finally publish the series’ seventh volume, Bulgarian developer Victor Atanasov, with his Plovdiv-based Prime Games, contacted the original writers around 2020 and started off his own videogame adaptation which, while still being incredibly faithful to the original experience, did a lot more to make it work in digital form that the old Java version could, or wanted to, releasing it in 2022 and slowly adding new books until it was finally complete around May 2024, or at least as complete as the book series, with the last two volumes available as DLCs.

Reading about the development of this adaptation and seeing how invested he is in interacting with the community, Atanasov’s passion for videogame RPGs and gamebooks really shines, and it’s very much obvious how this was a passion project for him, not to mention how he likely built his version of Fabled Lands by using the skills he developed while previously working on another videogame Gamebook-style RPG, Dust and Salt. Considering I had just returned to the Gamebooks in mid 2024, constantly thinking how well they could fit the videogame format, it was natural for me to give his work a chance once it was complete, something I ended up doing in January 2025, coupling Fabled Lands with my playthrough of a game that couldn’t have been more different if it tried, Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth.

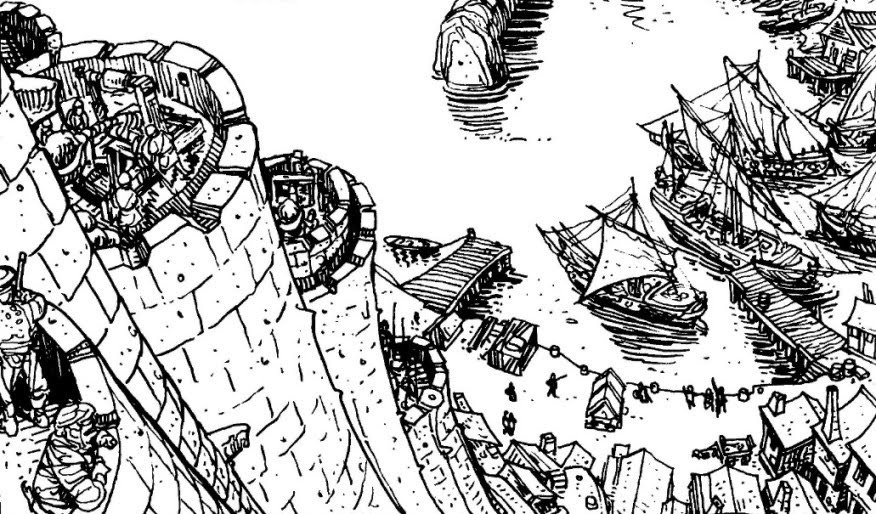

The main stylistic difference between the original and Prime Games’ rendition, as unfortunate as it is, is also one Atanasov could likely do nothing to avoid: I’m talking about the adaptation’s art direction, specifically its character design, that sadly has very little to do with the awesome Nicholson filler art featured in the books themselves (which, unfortunately, aren’t included in this videogame version), nor with the cover arts by Kevin Jenkins, whose illustration for Fabled Lands’ first volume I used as this review’s cover. Instead, the character sprites have a stylized, almost cartoony design style that felt like a rather poor fit with Fabled Lands’ overall tone, even if happily the maps, which are most of the graphical assets you will actually see in game, are fairly well done, more modern compared with the old ones designed by Arun Pottier, but still not without their own charm.

The original books let the player start his or her adventure in whichever region (or volume) he wanted, providing an higher starting level depending on the area in order to better accomodate its challenge, which, in turn, could end up trivializing the first volumes, once the character ended up visiting their corresponding areas. Atanasov, instead, has streamlined things by focusing on a single starting point: after creating the character, which includes a modicum of aesthetic customization, plus choosing your class with different starting allocations of the main six stats, the adventure will kick off on the Druids’ Island, which originally served as the starting area of the first volume, The War Torn Kingdom, providing a number of small quests used to introduce the player to the systems while also providing a number of options, since you can escape not just by ship, but also by using a magic portal with a variety of destinations. From here on, it’s sandbox sword and sorcery galore, with the player roaming the lands of Harkuna as they see fit.

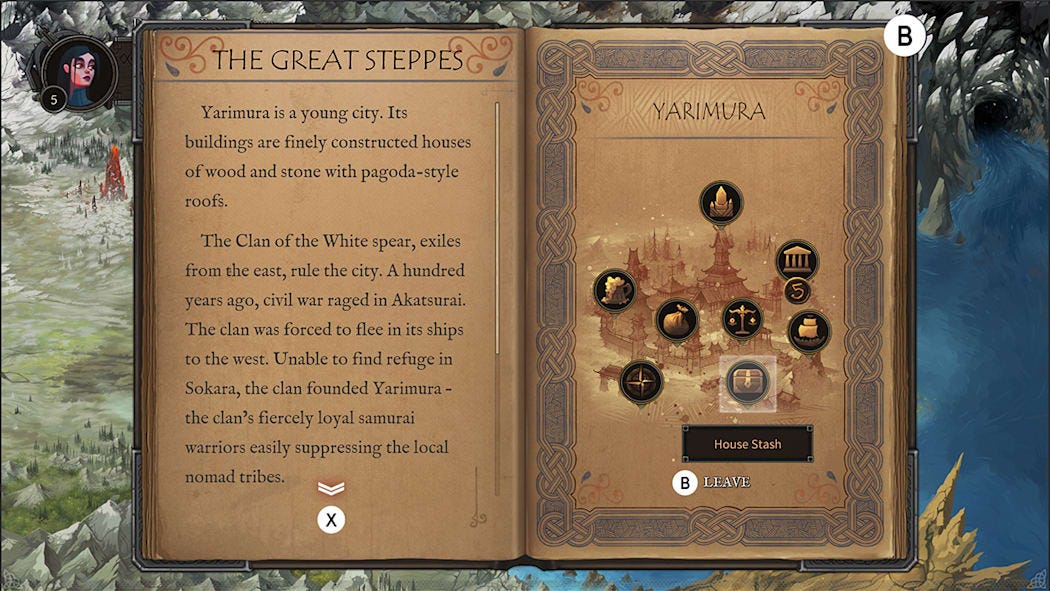

Be it the war-torn kingdom of Sokara, where a revolution has ousted the legitimate king, or the land of Golnir, with its fairy-tale mood, the Great Steppes with their deadly mix of cold, otherworldly menaces and untold secrets, the Uttaku Empire, where masked para-Byzantines decadent nobles rule with their faceless Emperor over a land of wonders and cruelty, or the Annon-Konu jungle, with its unique cultures and its rift to the spiritual realm, each region will provide countless opportunities for exploration and adventure, all served by travelling on the world map and choosing your options in a Gamebook-style interface inside each location, with towns being streamlined, compared to the originals, by using icons to represent the various locations.

There is a delicate, almost indefinible atmosphere pervading Fabled Lands that make it very much a product of its age, the early to mid ‘90s, even if its style actually echoes much older sensibilities: just a nudge would suffice in making this world more in line with the current tenets of dark fantasy, albeit an unusually high fantasy version of it (well, Malazan does exist, even if it too only fits those categories with a number of caveats), but it never takes that step, always retaining that dreamlike quality of old sword and sorcery that makes each mysterious cave, each new city, each distant tower, a potentially different universe where everything could happen without it feeling out of place. Considering the way this game is set up, composing a soundtrack could prove a bit challenging, since you need a number of “filler” tracks able to cover a variety of moods conveyed by the various events in each region, something that thankfully Fabled Lands is able to provide thanks to the talent of Cameron MacMillan.

From the onset, there isn’t a definite storyline you have to pursue: rather, you build your own by participating in events which, in turn, activate triggers (originally, the gamebooks used a number of code words, acting as a sort of title system, that you could check when asked in other paragraphs) that modify, or unlock, other events, possibly on the other side of the world. Finding a mysterious passage in a frozen cave in the steppes may be the key to saving a long-lost monarch in a different land, freeing a trapped wizard may make you the owner of a ruined castle, being stranded on a deserted island may open up a rare questline that originally was only available to characters starting their adventure with the third book, and so on.

By definition, all of this will happen by chance, not just because you will stumble upon those events, but also because most of them are actually randomized by throwing a pair of (simulated) dices offering a variety of different, sometimes repeatable, outcomes for the same actions. Many of those events also require a stat check which, like in tabletop RPG, confronts the challenge level of that situation with your value in any given ability, plus the result of your dice toss and, while some are merciful enough to allow you to check by using different stats, most are actually asking you to commit to a precise ability, which can easily get punishing if that isn’t your class’ forte, or if you haven’t travelled enough to power it up regardless of your starting occupation.

This makes Fabled Lands a veritable paradise for those interested in emergent narrative storytelling, with an incentive to pursue each questline due to the game’s progression system, which awards level ups (here called ranks) not after collecting some quota of experience points, but after reaching relevant narrative milestones. The other rewards tend to be useful items, be them weapons and armor or baubles with passive stat-up effects, which tend to be quite a boon given how frequent stat checks are. Interestingly, you can also gain points in any given stats during story events, often in completely unpredictable ways, but one has to be careful since those points can be lost, just as easily, if the situation goes south for our character.

This is, after all, a world of untold, and often unfair, danger, where reading a book in a random tower can completely reset your character’s hard-earned ranks, failing a test in a remote Magic Academy can actually be much better than passing it, village festivals can turn out to be more dangerous than ravenous beasts, damsels in distress can be exactly what they seem or something quite different and a random god can turn your hair into gold, which can actually be useful since you can start selling them for coins! In fact, people playing Fabled Lands completely straight, without keeping a number of saves to fall back to, could find themselves restarting their journey quite a bit, and, while the option to negotiate resurrection deals with a variety of temples was there since the original Gamebooks, making things a little less daunting, the game does have an Iron Man mode for those brave enough to stake their avatar on Hakkun’s benevolence, a gamble as alluring as it’s risky.

Combat, which is actually the lesser danger compared to unforeseen events and failed stats checks, has been completely revamped, transforming it into a rather simple tactical RPG affair, with action points spent to attack, move on an hexagonal grid or use a variety of skills and items, weapons influencing the AP costs of their use and their reach and a variety of buffs and other options linked to your class, even if any character can get proficient in a variety of playstyles over the course of their long journey, allocating stat points and buying or finding manuals to lear new abilities.

Even then, reading and fighting are far from the only activities available in Harkun: commerce and seafaring aren’t just a feature here, but actually a rabbit hole of sorts that can lead you to pursue completely different events while you’re gaming the markets and leading your fleet around the world, and the fact that a whole volume was dedicated to the Violet Ocean, the body of water separating the northern and southern continents, with Japan-like Akatsurai in the east, shows how central this feature was to the Fabled Lands experience, where seas aren’t just an easy way to link the different regions-books, but also a place where you can find countless adventures of their own, making Fabled Lands a sort of hidden Western Uncharted Waters. Given this comparison, it isn’t so strange that Fabled Lands’ seafaring is partially responsible for me finally giving a chance to GY Games’ Sailing Era soon after completing it.

While Atanasov fixed a number of easily abusable loopholes veteran readers-solo RPG gamers used to quickly gain ranks and money in Fabled Lands (far from all, though, as the Dragon Knights in Golnir can confirm), he didn’t raise the price of ships, which always were ridiculously low compared to equipments and other items. This may strike new players as an oddity, obviously, but it’s actually a precise game design choice, as it was back then with the analogic version, since the authors wanted the player to engage as soon as he wanted with seafaring, instead of treating it like a sort of late-game content to be postponed until much later.

There are countless other intervowen systems making Harkuna a world teeming with life, from the temples characters can join (or abandon - with possibly devastating consequences) and where they can contract the abovementioned all-important resurrection deals, banks to store and invest your hardearned profits, city homes you can buy to use as a convenient stash you can actually access from every other house you own, class-related contents, an hidden event to change your class dozens of hours into the game, mysterious tomes with incredibly useful effect such as warping between a set of locations and, many, many others, making it impossible to see everything Fabled Lands has to offer in a single playthrough.

As mentioned, all this narrative open endedness has a price, if one considers it as such, namely the lack of a proper ending for this solo RPG experience, with major quests altering the world in noticeable but mostly not too drastic ways and the adventure potentially going on forever, or until the player decides to retire their character after fulfilling some sort of self-appointed goal like exploring the whole world and reaching max rank.

Still, now that all the published Fabled Lands material has been adapted in digital form, with the exception of the Keep of the Lich Lord adventure module (which is actually the adaptation to this setting of an unrelated Gamebook originally part of the Fighting Fantasy series, later retooled to connect with the world of Harkuna), Fabled Lands stands as one of the most interesting and evocative sandbox experiences in recent Western RPG memory, and one with plenty of historical relevance for those interested in the crosspollination between different forms of RPGs, solo-RPG campaigns and in the glorious days of Gamebooks.