Profezia, or how a digital gamebook became the first Italian RPG

Developer: Trecision

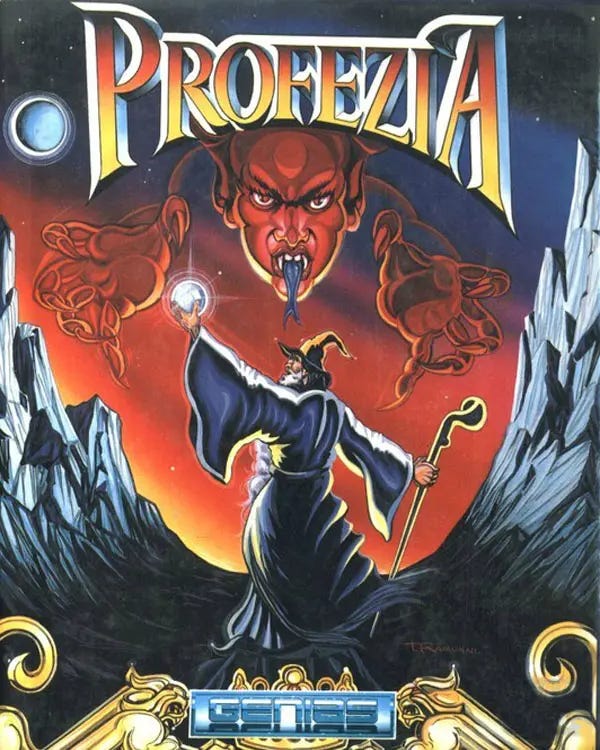

Publisher: Genias

Director: Edoardo Gervino

Scenario writers: Edoardo Gervino, Patrizia Albigini

Art direction: Gabriele Pompeo

Genre: Gamebook RPG, with underlying triggers, or possibly stats, hidden from the player

Progression: While the game is quite short, its branching narrative, randomized riddles and unforgiving nature actually make it quite replayable

Country: Italy

Platform: Amiga, MS Dos

Release date: 1991

Status: completed around 2010, then again in July 2025 just before writing this piece

While so far I’ve discussed the history of videogame RPGs developed in a variety of geographical contexts like Japan, the United States, France, China, the Russian Federation, Indonesia and South Korea, I haven’t had a chance to delve into the RPG output of my own country, Italy.

This isn’t particularly strange, though: while Italy had a lively tabletop RPG scene since the mid ‘80s, our videogame RPG development, same as our videogame industry at large, has always been a smaller affair compared to other European nations like France, Germany or Poland by pretty much every meaningful metric, not to mention how, in our country, the videogame medium never shared the cultural acceptance and financial incentives accorded to it by, say, the French government, with EU-related funding acting as the main crutch outside of some sporadic, and fairly recent, initiatives and a number of Italian developers, like Vampire Survivors’ Luca Galante, only finding success after leaving Italy itself.

Then again, despite this overall unfavorable situation, Italian developers still created a number of RPGs over the decades, mostly developed by small, independent teams that were often influenced by foreign trends rather than by specific Italian traits, which is to be expected given the lack of a successful RPG-focused team or franchise able to inspire other Italian developers like Arkane or Spiders were able to do in France, PiranhaBytes and Daedalic in Germany, CDProjekt in Poland or even Larian in Belgium, just to name a few.

Even so, albeit on a smaller scale, Italian RPGs still have their own unique quirks, with one of their most interesting traits being the outsized inspiration provided by gamebooks, the unique choose-your-own-adventure fantasy, mystery and sci-fi-themed books that had the player navigate hundreds of paragraphs of intricate interactive stories, often having to deal with complex inventory and combat rulesets loosely based on proper tabletop RPGs.

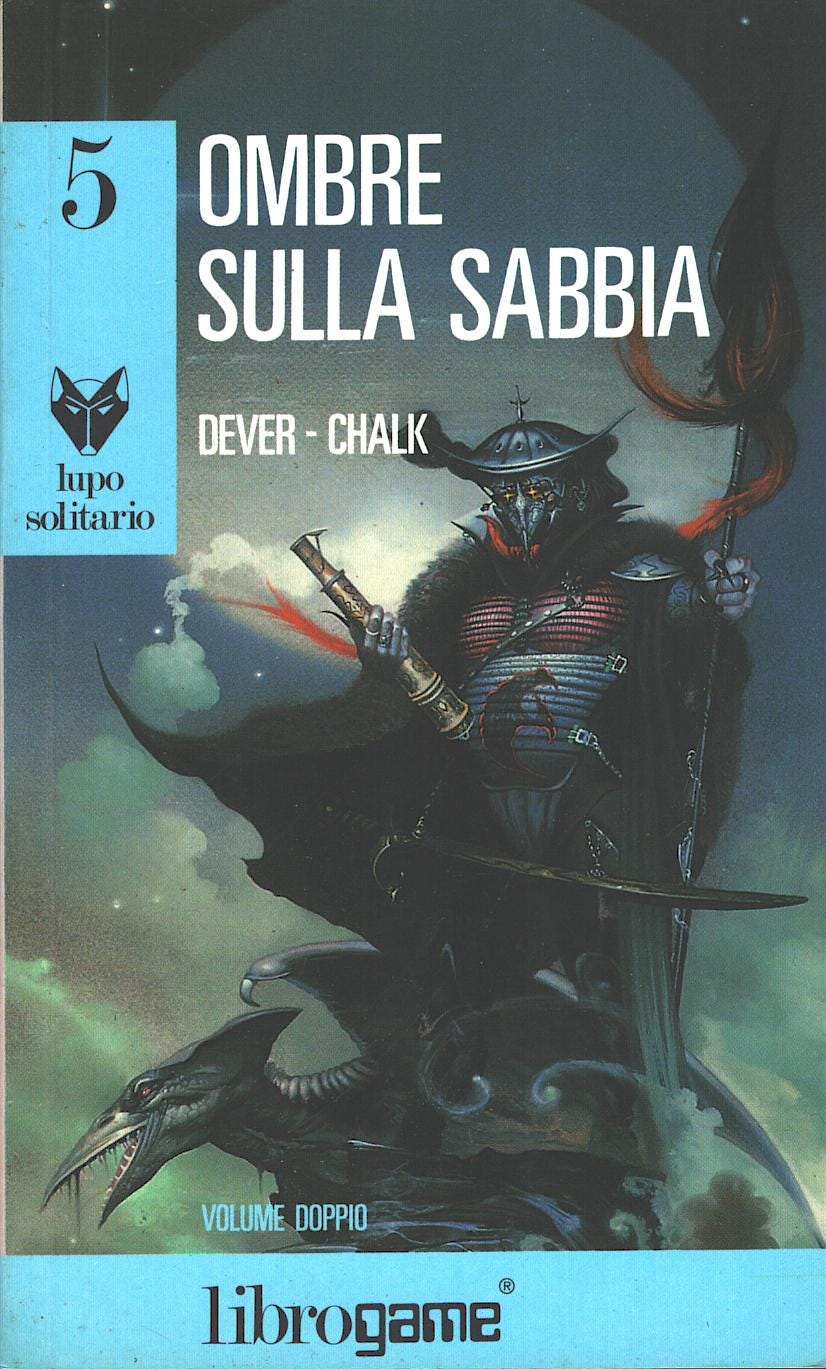

This unique genre, nowadays mostly forgotten outside of the niche interested in solo RPG experiences, was born in the United States in the late ‘70s, with Italian publisher EL (already known for publishing some of the first Italian tabletop RPGs, like Kata Kumbas) releasing the first translated librogame (with “libro” being the Italian word for “book”) in 1985, soon extending its lineup to dozens of volumes, including incredibly successful series such as British author Joe Dever’s Lone Wolf (known by Italians as “Lupo Solitario”, with a number of localization changes) and Oberon the Wizard. In the ‘90s, Librogames were popular enough to deserve their own sections in most Italian bookstores, with their success slowly fading around the turn of the century and their final disappearance outside of niche outlets around the early ‘00s.

Then again, they were so beloved (including by yours truly) that, when their young readers ended up in their 30s or 40s later on, the gamebook genre saw a nostalgic resurgence due to the efforts of Italian publishing houses such as Vincent Books, which went so far as to help genre veteran Joe Dever to complete his Lone Wolf series, with a number of volumes initially released in the Italian market before they even had an English print, not to mention new reprints for all the 28 old volumes, special limited edition and so on, also fostering a new wave of Italian-written gamebooks and even an Italian-developed videogame RPG spin-off, Joe Dever’s Lone Wolf, complementing a videogame-related trend that also included other efforts, often mixed with proper visual novels, like with Russia’s The Life and Suffering of Sir Brante or the Bulgarian adaptation of the US sandbox gamebook series Fabled Lands).

All things considered, then, it isn’t so strange that the very first Italian RPG, Profezia (Italian for “prophecy”), released on Amiga and MS DOS in 1991, instead of following in the footsteps of contemporary Western RPG hits like the Wizardry, Ultima or Might and Magic series that influenced so many titles in Japan, France and other countries, is actually an early videogame rendition of gamebook-style RPGs, taking an hard stance even within its marketing in order to distinguish itself from proper adventure games, in a timeframe where the boundaries of RPGs and adventure games were already kinda nebulous and series like King’s Quest were often described as RPGs, even if that crosspollination still persists even today, with titles such as Obsidian’s Pentiment.

Developed by Trecision, Italy’s first proper videogame developer which was based in Rapallo, a Ligurian town near Genoa, Profezia featured a scenario written by Edoardo Gervino, one of the company’s founders, and his wife Patrizia Albigini, focused on a fantasy story set in Medieval central Italy right before the end of the first millenium, in a small area centered upon the town of Capistrello. Nowadays, Capistrello is part of the Abruzzi region but, back in the tenth century, it was one of the core castles of the Marsican county governed for centuries by the Berardi family, which claimed to be descended from Charles the Great himself but ended up being ultimately beaten by another Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, who combined the power of the Hohenstaufen dynasty with the Norman Sicilian kingdom.

While the game isn’t really interested in delving into the area’s rich history, instead repurposing its locales for its fantasy story, it does reference a number of places in a geographical context even most Italians aren’t really aware of, even if I haven’t been able to verify why Gervino and Albigini ended up choosing such an area as the setting for their first title, especially since Capistrello is quite far from their own Liguria.

Whether one of them was a native of the Abruzzi, they vacationed in the area and were impressed by its landscapes or one of them had some academic interest in Capistrello and its surroundings, their choice was still an interesting one, as the Marsica, whose name derives from the ancient Marsi people who fought against the Roman Republic in the Social Wars, is an area mostly untouched by Italian fiction.

Profezia’s beginning saw a modern-day gamer starting out the game itself and being drawn into a space-time rift to inhabit the body of an Italian mercenary, possibly a reference to the Avatar in Origin Software’s Ultima franchise, with the player soon discovering he has to stop evil Duke Attilio of Capistrello before he uses the Corona Aurea (Golden Crown) to perform an evil ritual in order to gain untold, dark powers. This setup shouldn’t be so surprising, considering what is now called isekai, sometimes even outside the bubble of Japanese entertainment, has long been a mainstay of fantasy fiction.

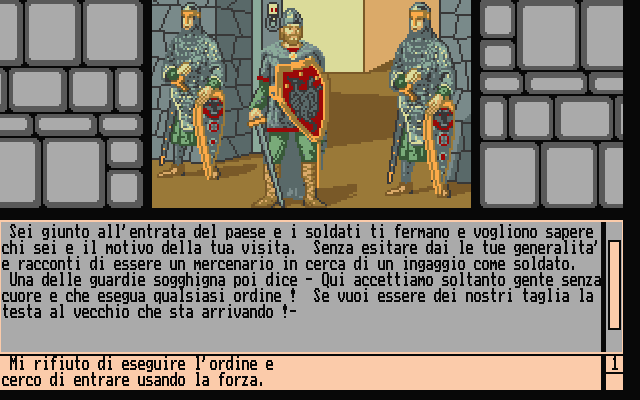

Unsurprisingly for a game presenting itself as “not an adventure, but an interactive book” on its on box, Profezia is structured like a proper gamebook, with a number of traits that nowadays would be associated with the visual novel genre in the videogame space, like the player being able to react to the events by choosing a number of actions (the Spacebar is used to switch between all the available reactions, confirming the chosen one with Enter), affecting both the story’s minute progression, with a large number of branching events, and its ultimate outcome.

As with most old-school gamebooks, Profezia has absolutely no qualms in handling the player unforeseen game overs, making trial and error an integral part of this Marsican adventure. Then again, the game’s really short play time makes it highly replayable, and the developers went so far as to make a number of its riddles randomized, in order to avoid the player trivializing further playthroughs.

One of them is kinda amusing, with another character’s mother-in-law teaching the player the recipe of a cake used to charm the evil Duke if he can solve her riddle, but not bothering to tell him if his answer was correct or not, with the main character thinking he has secured the right recipe only to get uncerimoniously killed later on when the cake turns out terrible, angering Capistrello’s court.

While the game doesn’t have a proper inventory or status screen, it also has a noticeably complex array of triggers, remembering the character’s health, his money and the items and information he was able to obtain during his quest, which will all end up playing a role in the ultimate success of the adventure’s last stretch in Capistrello castle.

Even if getting to the end can be a bit of an annoyance until you figure out all the available events and how they interact with each other, thankfully Profezia features rather gorgeous pixel art CGs created by Gabriele Pompeo, who ended up working on some of Trecision’s later efforts. Among them there’s also a single risque image and, while the game only briefly touches on adult contents, Trecision choose to be quite upfront about it, having it featured on the back of the game’s own box, not to mention its promotional material, in a way that ended up making those contents seem way more prominent than they actually were.

Even if this is just speculation on my part, I feel this also played a role in Profezia having a very small distribution run inside Italy (and no English localization whatsoever, which isn’t that surprising, considering most European videogame industries back then could be a bit insular in that regard, meaning people interested in trying it using DOS Box should be aware of the language barrier) and ending up staying kinda obscure, with most Italian gamers back then not even knowing about its existence until it was re-discovered around the late ‘00s and early ‘10s.

Speaking of Trecision, despite the attempt to distance Profezia from traditional adventure games, most of the later efforts of Gervino would actually end up focusing in that genre, while Trecision slowly grow by absorbing a number of teams located in different areas such as Lombardia and Campania, ending up as one of Italy’s biggest videogame developers by the turn of the century, while also dabbling in football simulations (which were, and still are, one of the most popular videogame genres in Italy) and early phone-dedicated games, long before smartphones existed.

At the time, fairly simple phone games were developed in a number of markets, sometimes including RPGs, like with the DoCoMo FOMA900 cellphone titles in Japan which saw a number of Japanese RPGs in its lineup, with titles like the Tales of Mobile line of Namco’s Tales series.

Unfortunately, in 2003, soon after releasing an adventure game based on Alfredo Castelli’s renowned comic Martin Mystère (the game, a Java title available for Wind phones, sadly seems to be lost forever, same as most of Trecision’s games for early cellphones), Trecision ended up being yet another victim of the Dot Com crash, albeit indirectly, being forced to go into liquidation after the downfall of France’s Cryo Entertainment, with which Gervino had just established a partnership, expecting to get funding for his company’s ambitious growth.

As we discussed elsewhere, the impact of this crisis was a disaster for France’s videogame industry, which had already balooned to a remarkable size in the ‘90s, but Italy, having a less developed videogame scene to begin with, mostly composed by smaller teams, ended up not being affected in such a devastating way.

Regardless of Trecision’s later history, though, I feel Gervino and Albigini’s Profezia still stands strong as a fast-paced, competent early example of videogame gamebook, showcasing one of the most peculiar traits of Italian RPGs, focused not on the most famous Western RPGs of its time, like the Wizardry, Ultima or Might and Magic franchises that inspired countless RPG efforts in Japan, France, Germany and other countries, but on a literary solo RPG experience repurposed in the videogame medium that ended up resurfacing in other Italian titles later on, like with some of Winter Wolves’ lineup or with the abovementioned Lone Wolf RPG by Forge Reply.