Triangle Strategy, Asano and Artdink's 2D-HD tactical epic

Developers: Square Enix - Team Asano, Artdink, Netchubiyori

Publishers: Square Enix, Nintendo

Producer: Tomoya Asano (Grandia Xtreme, Valkyrie Profile Covenant of the Plume, Final Fantasy 4 Heroes of Light, Bravely Default, Octopath Traveler), Yasuaki Arai

Scenario writer: Naoki Yamamoto (Tales of Xillia 1-2, Tales of Zestiria, Tales of Berseria)

Soundtrack: Akira Senju

Character design: Naoki Ikushima

Genre: Tactical JRPG, with cities you can directly explore between missions à la Shining Force

Progression: Linear in the first few chapters, then with two or three branches in each chapter offering different battles, recruitable characters and plot developments while still keeping the scenario roughly on the same tracks, culminating in an end game choice between three different paths that aren't linked with previous choices. There's also a fourth path, the Golden or true ending, which requires taking a precise set of choices during the whole game.

Platform: Nintendo Switch, then PC, Xbox Series and PS5

Release date: 4\3\2022 (Switch), August 2025 (PS5)

Status: Completed on 30\8\2022

In the early ‘10s, Square Enix experienced a rather major shift after Yoichi Wada stepped down as CEO and, with Bravely Default on 3DS being a noticeable success and making a case for lower budget efforts catered at more traditional RPG audiences, the new chairman Yusuke Matsuda built up a new strategy aimed at diversifying his company’s lineup, trying to develop a wider variety of games in different subgenres with a variety of production values alongside the mainline Final Fantasy and Kingdom Hearts offerings.

While this new commitment was pursued in a variety of ways in the next decade by using internal and external teams, like with Tokyo RPG Factory’s nostalgia-driven efforts, Akitoshi Kawazu slowly making the SaGa franchise relevant again through a long-term plan focused on remasters and new entries, the Mana series being handled to both internal and external teams and Front Mission being licensed to Forever Entertainment, the major focus was always Tomoya Asano’s own team, Business Division 11, which kept delivering commercially successful turn based JRPGs with an heavy slant on job systems and peculiar systems, tracing back to Four Warriors of Light on NDS and continuing on with the abovementioned Bravely Default, its sequel and Octopath Traveler on Switch.

During Octopath’s development, Asano had already started to envision working on a different subgenre, tactical JRPGs, in order to tackle another format which nostalgic Square Enix fans often longed for, especially with the Ogre Saga and Final Fantasy Tactics franchises being long dead outside of remake and remasters. The success of then Switch-exclusive Octopath’s 2DHD art style, which soon became the signature of Asano’s further works, meant this new tactical effort would also follow the same aesthetic template, albeit with a number of twists, while also retaining Naoki Ikushima’s talent as character designer.

While his Business Division 11 ended up being merged into the new Creative Business Unit 2 during Square Enix’s internal reorganization in late 2019, things didn’t really change for Asano and his team, who could always count on a small number of key staffers acting as liaisons and overseers for outsourced developers working on their projects, like Silicon Studio for the 3DS Bravely Default titles or Acquire for Octopath, and so they ended up choosing Artdink (alongside Netchubiyori in a supporting role) to work on what would end up becoming Triangle Strategy, initially developed as a Switch exclusive and slowly trickling to other platforms over the years.

Picking up Artdink instead of a developer with a stronger tactical pedigree was an interesting choice, since Asano himself had never worked on tactical JRPGs aside from a supporting role in the unique Valkyrie Profile: Covenant of the Plume, and even Artdink, despite having a long history as an outsourcing-focused developer (including old ports for some of Quest’s Ogre games) and as the creator of a number of peculiar simulative-oriented franchises like the Uncharted Waters-style Neo Atlas and mecha building Carnage Heart, never dabbled in that design space. Kazuya Miyakawa, Artdink’s project director and Asano liaison, had himself worked on titles like Carnage Heart EXA and two Sword Art Online-related titles, with Triangle Strategy being his very first tactical RPG project.

This is why, when Triangle Strategy was unveiled, I expected Asano’s new effort to turn out as a rather safe, nostalgic tribute to Tactics Ogre and Final Fantasy Tactics, avoiding to tackle new gameplay ideas with their very first effort in this subgenre. Instead, Asano and Artdink ended up going in a very different direction, building their own noticeably different take on tactical JRPGs without trying to ape Yasumi Matsuno’s works, rather picking up some key elements from the likes of Shining Force, Tactics Ogre and Jeanne D’Arc in order to foster their own vision.

Interestingly, when choosing Triangle Strategy’s scenario writer, Asano ended up picking up Naoki Yamamoto, who had just worked on the stories of Namco’s Tales franchise from Xillia to Berseria. While Takumi Miyajima's Tales of the Abyss is still the go-to game in that series as far as morally grey characters and scenarios go, all those titles also tried to explore conflicts between different factions with unconciliable priorities, sometimes impacted by their worlds' supernatural rules and entities.

With Triangle Strategy's surprisingly low fantasy setting, where the commerce of salt and iron plays a central role, often betraying A Song of Ice and Fire’s influence (something Square Enix had also tried to pursue with Lancarse’s DioField Chronicle in the same timeframe), Yamamoto finally had the perfect context to fully explore those themes, and the way personal and ideological conflicts are slowly built and are able to shape the player's perception is proof of his success.

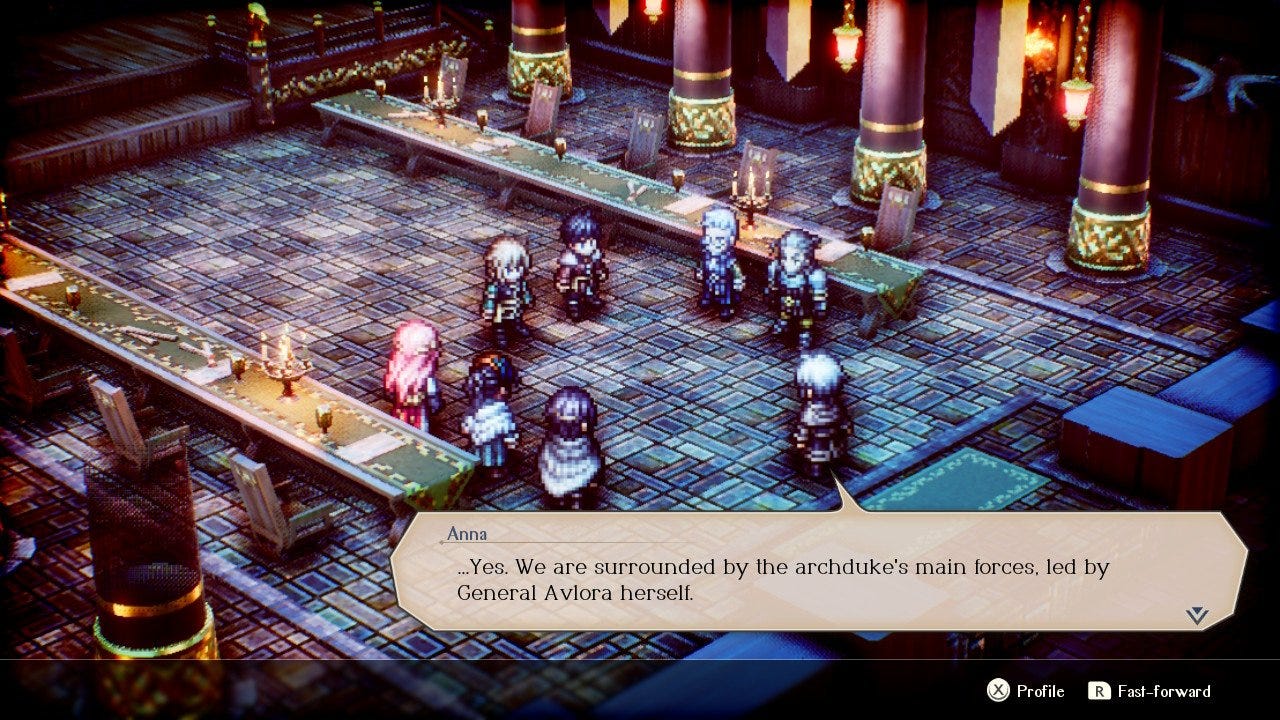

The game's first few chapters, following young aristocrat Serenoa of House Wolffort, a noble fiefdom in the kingdom of Glenbrook, as he met Frederica, his betrothed from the nearby Archduchy of Aesfrost and starts meddling with the politics of the land of Norzelia and its three countries, are often criticized for their slow build up, but they actually reminded me of one of my personal favorite turn based JRPGs from the sixth generation, Suikoden V.

Both games had to set the stage for major political conflicts and upheavals, but their writers realized that, to make those developments seem interesting and organic, they had to slowly foreshadow them in a prologue of sorts, gradually introducing characters and factions while also focusing on world building, without the easy crutch of lore dumps that would make the player less invested in future developments.

Of course, there is a price to pay for this choice, and Triangle Strategy ends up introducing itself with a rather glacial pacing and a cutscene-to-battle ratio more in line with visual novel-tactical JRPGs hybrids like Aquaplus' Utawarerumono or Tears to Tiara franchises, rather than with the games most people expected it to imitate, like Matsuno's Tactics Ogre and Final Fantasy Tactics.

While Triangle Strategy keeps being very story driven until the very end, with plenty of optional cutscenes also unlocked throughout the game as nodes on the world map (something that reminded me of SaGa Frontier 2’s unlockable side events), in-battle dialogues triggered by characters you didn't even know were related and so on, its pacing definitely improves after the introductory chapters, and the payoff for its slow start ends up paying some hefty dividends.

A proper build up doesn't just make story events way more impactful, but also introduce the geopolitical and ideological differences between the diverse viewpoints Serenoa will have to sail through while deciding how to face the challenges in each chapter's crisis. Unlike with Tactics Ogre’s Denam, choices in Triangle Strategy aren't made directly by our House Wolffort protagonist, though: rather, he is able to take a stance only after his privy council deliberates an issue and votes about the best way to solve it by using an ancient artifact, the Scales of Conviction.

![Triangle Strategy [PC] | REVIEW - Use a Potion! Triangle Strategy [PC] | REVIEW - Use a Potion!](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YVMh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F96a24355-4653-48c0-9ed2-dcf71e030f6d_1200x675.jpeg)

Each chapter’s branching point will see Serenoa’s main allies debating current events and offering two or three different paths to follow, with our young protagonist trying to build up a consensus toward his preferred option by persuading dissidents to follow his (or rather, the player's) vision. This is accomplished by talking with each core party members, bringing up dialogue options that resonate with their beliefs and worries.

Some of those options, though, are unlocked in the game's brief exploration segments, a bit reminiscent of old Shining Force games: before each choice, you will be able to ease your mind by exploring the town or fortress you're currently visiting, finding hidden treasures and talking with NPCs, which will give you new topics you can then use while trying to convince your retinue. This keyword system, while not as prevalent as in other JRPGs like Final Fantasy II or Feycraft’s Prisoner, is still an interesting touch that can be possibly traced back to Netchubiyori, a visual-novel focused developer that helped out Artdink during Triangle Strategy’s development.

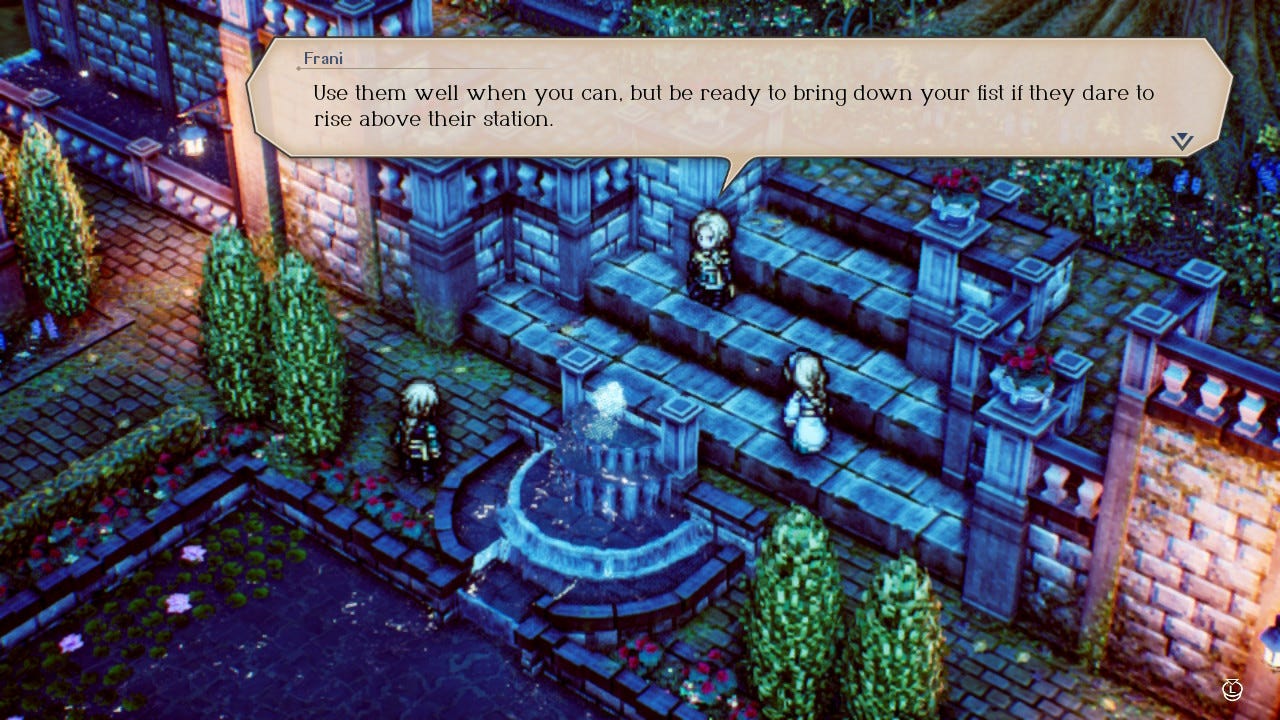

Since the game’s early acts, Serenoa’s main three counselors are actually able to assess their identities and their unique take on their world’s ideological landscape: his young wife Frederica, an illegitimate daughter of the neighboring Archduke which is also part of the heavily discriminated Roselle people, prince Roland of Glenbrook, which will soon find himself in a very unwelcome position which will deeply influence the way he views his role and the continent’s political situation and Benedict, House Wolffort’s chief advisor which embodies a mix of Machiavellianism and the “realist” school of geopolitics, like a fantasy version of Hobbes and Mearsheimer.

A bit like in the Shin Megami Tensei games, those three characters also act as avatars of sorts for the game’s own alignment system (referenced in the game’s own title), its three different Convictions, Freedom, Benefit and Morality, which aren’t accrued just by making story choices, but also by actions taken while exploring towns or fighting during the game’s own missions. The optional events allowing the recruitment of new characters, among a number of other things, are also triggered by the Conviction points obtained by Serenoa.

Story branching is yet another design trait where Triangle Strategy ended up distancing itself from Tactics Ogre: while Serenoa’s choices have a deep effect on each chapter's progression, completely changing their story developments, their battle maps and even which characters you end up recruiting, their impact on the story as a whole is often negligible, unlike Denam’s life-changing decisions leading to Let Us Cling Together’s three paths.

Even then, Triangle Strategy does commit to different outcomes during its final stretch, where Serenoa will actually have to choose between three strikingly different paths that will lock you into one of the endings, again with their own battles and events which ends up being much more varied compared with Let Us Cling Together, showing how Asano reversed the way branching scenarios were handled compared with Quest’s classic.

While the consequences of a number of choices are fairly predicatble, I must say the game managed to surprise me in a number of instances, like with Roland's ending, which took the story in a really wild direction I actually mused upon during the game's last stretch without imagining it could ever become a real option.

This also shows how previous choices, despite not having a lasting impact, can in fact help create context for one of the endings, as that morally dubious scenario becomes way more coherent with the Prince's characterization and his relationship with aristocrats and common folks if you stayed with him during one of the previous chapters.

Then again, the game also features a secret ending which does require making some very specific choices throughout the game, setting up the political and war situation in a precise way. While this follows the usual tenets of JRPG true endings, I wouldn't necessarily say the game treats its Golden path that way, rather positioning it as a choice that is able to shatter Serenoa's reliance on the Scales of Conviction themselves.

Speaking of those, one rather amusing and very interesting side effect of House Wolffort's privy council-based decision making is the way the hardest and cruelest choices are made in a way that shields Serenoa from taking full responsibility, at least until the very final instances. In fact, seeing how Serenoa’s story ended up developing, there a number of instances where I ended up thinking that the young hero may actually be way more shrewd and Machiavellian than the other characters, and possibly even himself, give him credit for, simply due to his remarkable capability to use his role of ultimate arbiter by appealing to the formality of the voting system and the reliance on majority rule to avoid having to fully commit to their outcome on a personal level, regardless of how other parties are affected and how those majority were actually built by his own direct influence, which raises quite a number of interesting issues that are sparingly tackled by the game itself and end up as this game’s fairly unique example of so-called ludonarrative dissonance.

While its narrative ends up being noticeably different from Matsuno’s games in a number of ways, the game’s tactical systems are even more detached from Tactics Ogre and Final Fantasy Tactics’ well-established formula, itself based on an heavy focus on job systems and character customization through skill mixing, often sidelining complex maps and mission objectives and giving an outsized role to pre-battle planning and team composition.

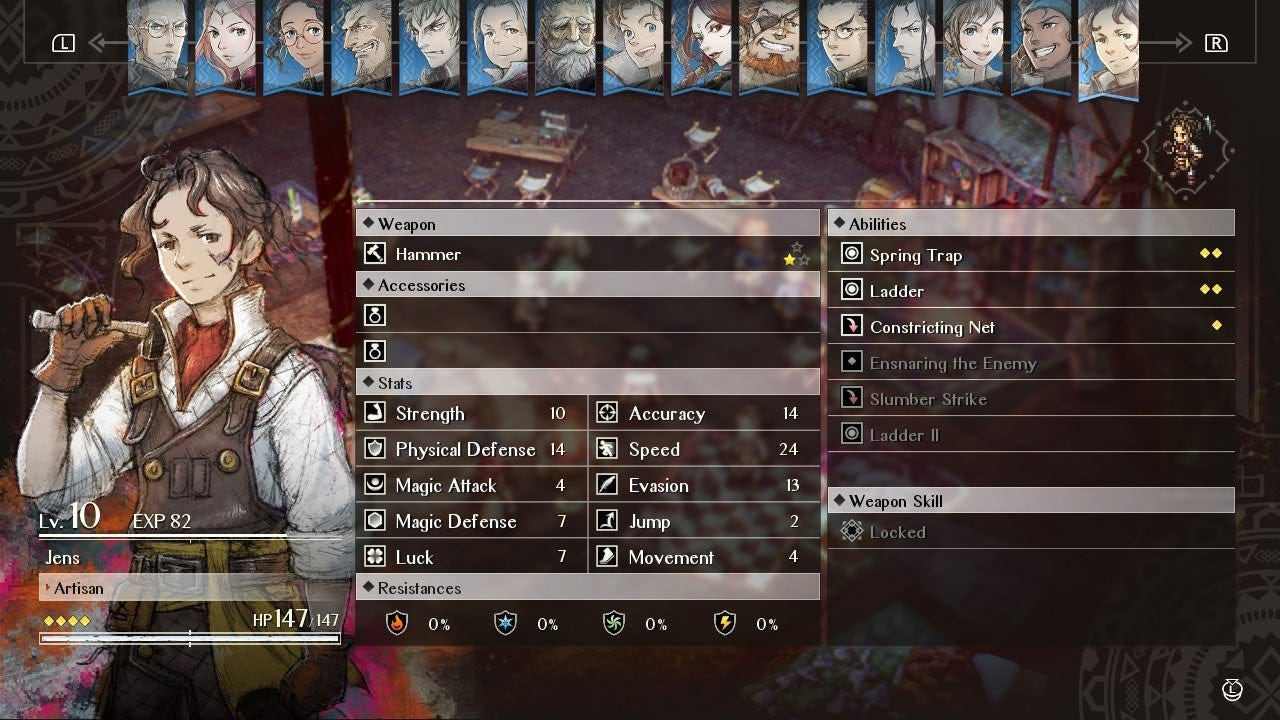

Instead, even if Triangle Strategy does provide a job system of sorts, it’s actually a much more subdued affair, a bit in line with Shining Force and older Fire Emblem games’ improvement on a character’s already established template, except units here are far more unique, with classes being built around them rather than them being yet another pawn based upon a pre-defined role. This was actually flaunted as part of the game’s core identity by Asano himself, alongside Triangle Strategy co-producer Yasuaki Arai, during a Nintendo interview, with Asano apparently being as enthusiastic as I was in placing random ice walls to delay enemy advances and create chokepoints.

Each of Triangle Strategy’s units has a precise, often irreplaceable use case, with their unique abilities and utilities not just in terms of combat skills, spells and buffs, which are extremely important, but also for the way they can interact with turn orders or status effects and, in a number of instances, for their unique positional capabilities, like with attacks with knockback capabilities, elemental spells able to reshape the map à la Bahamut Lagoon or Legend of Kartia with props like the abovementioned ice walls or with an incredibly fun character able to build ladders and place traps. All those traits are meant to synergize with one of the game’s greatest strenghts, namely its map and mission design.

While in the past decade tactical JRPGs have seen precious few games focused on maps trying to bring about scenarios featuring an interesting use of positioning and terrain features, especially if we don’t consider those that rely on mission-specific gimmicks like Fire Emblem Fates: Conquest, Triangle Strategy’s missions are mostly able to strike a grat balance between a degree of normalcy that lets the player build reliable strategies by focusing on a number of units while also testing their viability by providing a variety of challenges, wildly different mission objectives, a noticeable emphasis on height variance between each map’s different areas and a moderate use of unique systems that are able to make some mission unique (like with an early map featuring mine carts) without making gimmicks too frequent or prevalent.

The importance of this trait can’t really be overstated, since map design and mission design are some of the most important parts for a proper tactical JRPG experience, but, unfortunately, they seem to have become a bit of a forgotten art even for franchises that were able to routinely deliver on that front, like with Fire Emblem’s rather spotty record after Radiant Dawn, with its more narratively acclaimed entries often having fairly mediocre map design, like with Awakening or Koei-developed Three Houses, while those with rougher stories, like Conquest or Engage, ended up being much better in that regard.

If it had been developed more safely, I feel Triangle Strategy could have ended up as yet another manieristic take on Tactics Ogre, which in itself is a perfectly valid template for tactical JRPGs, recently followed with decent to good results by the likes of Rideon’s Mercenaries Saga series. Instead, Asano, Arai, Yamamoto, Miyakawa and the other developers were able to push a very different package, with a bold focus on world building that is able to pay off wonderfully in the game’s later stages while also crafting one of the best tactical JRPGs of the last decades due to the sheer variety of maps, missions and situations one can end up encounter, with the game’s branching scenarios granting it an outsized replay values while also making it easier to recruit new characters in further playthroughs due to the gradual accumulation of Conviction points.

While Asano’s team seems to be focused on continuing the Octopath franchise with Octopath Traveler Zero and its valiant attempt at repurposing gacha Champions of the Continents’ contents while pursuing new IPs set in different genres, like the upcoming The Adventures of Elliot bringing the 2DHD line to action JRPGs by mixing bits of Ys, Zelda and Seiken Densetsu in a very interesting way, one can only hope Triangle Strategy isn’t the last time they partner with Artdink (which is now busy working on the 2DHD Dragon Quest remakes) to craft new tactical experiences, and the fact the game has seen great sales for a new IP in a rather niche subgenre, with its recent Xbox and PS5 ports likely contributing even more, can make us cautiously optimistic in that regard.