Shandalar, MicroProse's RPGfication of Magic: the Gathering

Developer: MicroProse

Publisher: MicroProse

Producers: David Etheridge, Ned Way

Designers: David Etheridge, Ned Way, Todd Bilger, Sid Meier

Soundtrack: Roland Rizzo (Pirates! Gold, Sid Meier’s Civilization 2, Dragonsphere, Sid Meier’s Colonization)

Genre: Sandbox RPG with Magic: the Gathering matches in lieu of a combat system

Developer’s country: USA

Platform: Windows PC

Release Date: March 1997

Status: I journeyed throughout Shandalar far too many times between 1997 and the early ‘00s, and I still find myself starting a new game once in a while.

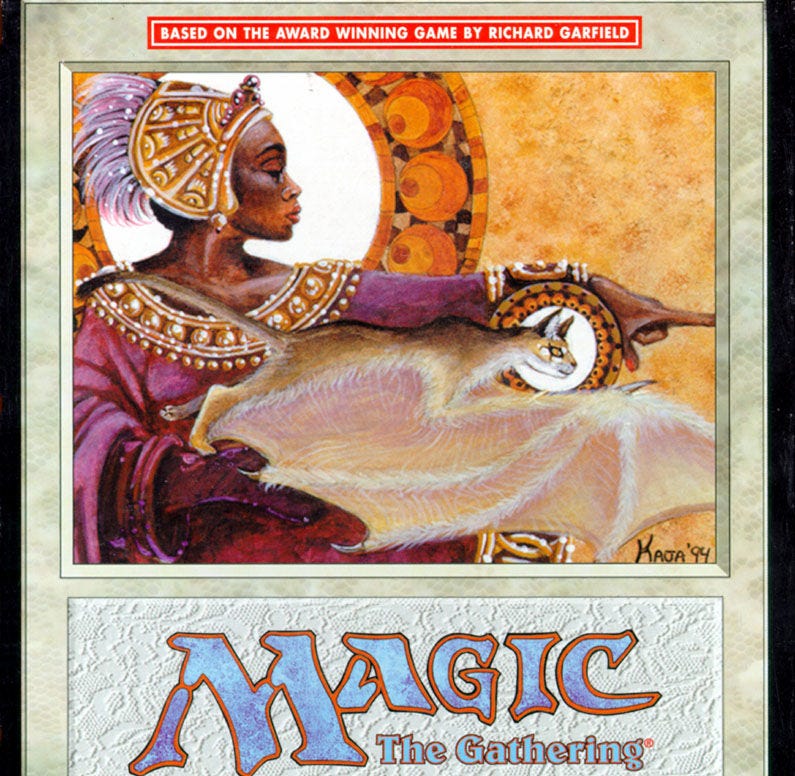

Back in late 1994, when I started playing Magic: the Gathering once my country's black-bordered release of the Revised set made its debut on the shelves of the stores selling RPG modules, fantasy books and wargame miniatures, trading card games (or TCGs) were an intoxicating, mysterious adventure that often involved even those who didn't play them. I still remember how, first with Mutant Chronicles' long-forgotten TCG, then with Magic itself, cracking a booster and finding a previously unknown rare card would make waves in your classroom, attracting both people who played the game and wanted to see something new and those who just wanted to look at the often gorgeous illustrations.

Back then, the concept of "meta" didn't exist for most players, there werent' online resources to instantly look at the full set or to gauge a card's deepest interactions, overall playability or value, English magazines like Duelist or Scrye were hard to come by and it was normal to see fellow children overlook powerful Dual Lands, now incredibly pricey, while drooling over huge, dumb and yet awesome summoned creatures like Shivan Dragon, Lord of the Pit or Force of Nature. Such was the blessed naiveté of those times, something that's hard to recapture nowadays for newcomers considering how the game, since then, has amassed dozens upon dozens of expansion sets and tens of thousands of different cards, with a growing amount of complexity and the need to account for game objects like tokens, counters and now, regrettably, even stickers, and this isn't even considering how new players today are more likely to start with either Arena or Commander, which, in their own ways, end up being both noticeably different experiences compared to kitchen table (or school desk, as it was often the case) Magic in the Revised days.

While some nostalgic players have created the Old School format, limiting the usable cardpool to the very first Magic sets, I argue that one of the best ways to feel the spirit of early Magic could actually be conveyed through a single player videogame, MicroProse's 1997 hit Magic: the Gathering, the last title Sid Meier worked on in that company before founding Firaxis Games and developing Gettysburg and Alpha Centauri. The game was later expanded with two expansions and re-released as Duels of the Planeswalkers (with planeswalkers being the players, rather than the card type introduced many years later), even if nowadays it's mostly known and referenced as Shandalar, due to its setting.

Even if trading card games and videogame spin-off are often a disappointing duo, as most Magic adaptations sadly show (Yugi-Oh is a different story, partly due to Konami being its IP holder), Microprose's attempt felt both fresh and faithful even at the time and, in my mind, is still the only really successful effort at combining a more-or-less traditional RPG experience with TCG mechanics, including a character creation screen that, while mostly limited to your planeswalker's appearance and the color of his or her randomized starting pool of cards - White, Blue, Black, Red and Green, all with their own unique traits, including the fabled Power Nine, cards only featured in the Alpha, Beta and Unlimited sets that nowadays are unfortunately treated more as financial assets than game pieces, even more so considering they’re banned in most formats.

After creating your character, the game will randomly generate a world map and throw your newbie planeswalker in the middle of his adventure (a bit like a previous MicroProse RPG classic, Darklands, randomized the player’s starting location in the Holy Roman Empire), providing a sandbox experience made of explorations, securing vital resources like money and food, roaming enemies to confront, dungeons to discover and random events to trigger, not to mention plenty of Magic cards to collect and use in one of your decks during your quest to free Shandalar from evil and become the strongest wizard. Quests given in cities would offer rewards not just in terms of resources, additional cards or hints to locate dungeons, but also by activating Mana Links, the way Planeswalkers associate themselves with various locations in order to draw their mana, a level up of sorts that improved your character's starting HP value during combat while also being really flavorful since establishing ties with the power of the land was the concept behind lands being used to produce Mana to begin with.

Battles themselves are actually fought like a proper game of Magic and use the same interface as the game's other mode, Duel, albeit with some differences compared to the tabletop experience, like the variable number of HPs for the player and the enemies, not to mention a controversial feature of early Magic that was dismissed soon after in the cardboard space: the ante. While Magic at the very beginning was a way wilder game, with no limits on the number of copies of a card you could use in your deck (hence the iconic Channel-Fireball combo) and rules about ante cards to make each match more tense, including cards that influenced the ante itself, like Contract from Below (a spell that would easily rank among the most powerful, if ante hadn't been banned), Microprose's adaptation could happily employ this feature without incurring in real-world issues about card ownership, and made it one of the best ways to gain new cards while fighting enemies (including delightfully complex ways to conjure cards you didn’t actually possess and then permanently acquire them after placing them as ante), even if magical merchants are another useful, and easily gameable, option.

While the game was obviously aimed at Magic fans, its overall experience was coherent enough to make it perfectly playable for someone who never dabbled with boxes and packs, adding a layer of discovery as each card was introduced that mirrored the TCG players' first, pioneeristic foray into Richard Garfield's game. In turn, experienced players could slowly work toward building a digital version of their own decks by finding the cards they needed while travelling through Shandalar, making the game as varied as the potential complexity of the cardpool it employed.

Even factoring the multiple difficulty levels available at the beginning, the heavy amount of randomness in card pools, enemies and events made the game fairly challenging on its own, a challenge that was fostered and made manageable by the limited "Old School" cardpool, which offered a vast, but still fairly easy to recall, amount of variables. Over the years, fans have modded Shandalar by adding many new sets and mechanics but, even ignoring the very noticeable artistic clash between the game's '97 interface and the artworks and layouts of more recent cards, I'm not sure the quantitative improvement also fostered a qualitative one, unless one desires a potentially broken experience similar to a tabletop Magic Chaos Draft.

That said, Microprose's game did feature some cards never seen before (or after) in physical form: the Astral cards, a set of 12 spells, were designed explicitely for the videogame space, being based on randomized effects that would have been difficult or outright impossible to replicate in real-world matches. Interestingly, almost two decades after Shandalar, this idea was reused by Wizards of the Coast itself for the Alchemy cards featured in Magic's newest online platform, Arena, even if some of them are just previously released cards that were subjected to online-only nerfs. Speaking of online platforms, Duels of the Planeswalkers introduced the Mana Link mode to play online matches in 1997, well before Wizards of the Coast published Magic Online in 2002.

Cards weren’t the only spells in Shandalar, though, as MicroProse correctly assessed that a proper RPG needed some sort of qualitative progression even outside battles, a design space akin to Birthright: Gorgon’s Alliance’s Realm Spells, themselves taken straight from the AD&D Birthright campaign setting, which affected the grand-strategy layer of that game while regular spells were employed during dungeon crawling. Shandalar’s own answer was provided through World Magics, rare skills that could be either permanent or usable, with a chance to lose precious amulets. Those spells provided a range of useful abilities like enhanced mobility, teleport or an increased number of cards in the village shops.

Overall, MicroProse's effort ended up creating an almost perfect marriage of RPG and card game, seamlessly combined to the point of feeling absolutely natural, without making either the card fights or the overworld explorations feel tacked on. That no one has been willing, or able, to build on this kind of setup is frankly a shame, and it’s even more striking once you notice how, Yugi-Oh games aside, card games still managed to have an impact in the wider RPG space, both as the main focus, like in Neverland Card Battle or the Hand of Fate and Voice of Cards series, as core features of an otherwise more traditional turn based combat systems, like in Legend of Kartia or the Baten Kaitos and Lost Kingdom franchises, or as minigames of wildly difference importance, like with Final Fantasy 8 and 9, KoTOR's Pazaak, The Witcher 3's Gwent, the Trails of Cold Steel saga's Vantage Master (itself taken from another storied Falcom franchise) or Bravely Default 2's Blind and Divide.