Energy Breaker, Lufia's forgotten tactical prequel

Developer: Neverland

Publisher: Taito

Directors: Osamu Watanabe, Akihiro Suzuki

Character design: Yasuhiro Nightow (Trigun)

Soundtrack: Yukio Nakajima (Chaos Seed, Lufia)

Genre: Tactical JRPG with direct explorations and adventure game-like NPC interactions

Progression: mostly linear, with optional events

Platform: Super Famicom

Developer’s Country: Japan

Release date: 29\7\1996, then fantranslated in English in early 2012 by Disnesquick and satsu

Status: I played the first two or three hours in mid 2012, then started anew after a long hyatus and completed Energy Breaker on 10\11\2018

Back in the late ‘90s, team Neverland’s Estpolis\Lufia series on Super Nintendo was one of many JRPG franchises whose western perception ended up getting hit by publishing and localization choices: while the first game was published in North America, Europe only managed to get Lufia 2, which was immediately renamed Lufia: Rise of the Sinistrals since we never got the first game. I ended up loving it despite buying a Spanish-translated version, a mistake that forced me to learn a bit of that language just in order to progress through the game’s many puzzles and, when I finally had a chance to play the first entry years later, it wasn’t that much of an issue given Lufia 2 was actually a prequel. What I didn’t know at the time was that Lufia had yet another prequel I won’t be able to fully experience until 2018, two decades after I first dabbled in Maxim’s world: Energy Breaker, art-directed by Trigun's Yasuhiro Nightow and published by Taito in 1996 on Super Famicom.

While Neverland’s popularity among JRPG connoisseurs is still tied to its early Lufia games, it’s fair to say the team managed to stay somewhat relevant since the 16bit days until its demise in late 2013, first with Lufia, then with Shining's action-JRPG spin-offs like Neo and EXA and, after that, with the Rune Factory series. Some of its best efforts, though, were unable to get a timely localization, thus ending up in the import-only limbo so common with Super Famicom JRPGs. This was the case for Energy Breaker which, being released fairly late in the Super Famicom's life cycle and seeing poor sales in Japan (around five thousand copies going with the fantranslators' own commentary, even if I haven't been able to independently verify this through the usual Famitsu and Media Create sources), ended up staying there for good. Fortunately, after more than sixteen years since its original release, a valiant fan-translation effort by satsu and Disnesquick made it finally possible to enjoy Energy Breaker in English.

The town of Olga acts as an hub of sort, even if the island of Zemlya does have another major settlement.

While fan translated Super Famicom games are often nostalgia trips, Energy Breaker is so experimental it doesn’t really fit with the kind of experience one would expect of a stereotypical late ‘90s JRPG : its dialogue interface, for instance, has some interesting adventure game-style options that let you change your own tone towards an NPC, find new conversation topics to investigate or show them key items to unlock rewards or optional events, something almost unheard of in JRPGs outside of Growlanser’s alignment system and a few other cases. This unusual focus also extends on objects and furnitures, which you can interact with extremely frequently and which often hide treasures, collectibles or funny monologues on the protagonist's part. Energy Breaker also sports a mix of traditional explorations and tactical combat directly triggered and set in the explorable areas, a bit akin to Treasure Hunter G or the Arc the Lad series, and it has a really colorful isometric presentation which aesthetically sets it apart from lots of other SNES JRPGs. Its setting itself is quite unique, mixing western, fantasy, steampunk and sci-fi traits and, last but not least, Energyy Breaker also features an unique customization system, involving light and dark versions of the four elements that you can power up in order to get new skills (with the noticeable exception of a character that will first need to absorb said skills by defeating monsters in hand-to-hand combat).

Interacting with random objects will sometimes unlock funny monologues, and this particular one will also see a change once you get a certain party member.

Its uniqueness is also expressed by its narrative: not only it's one of the few JRPGs of its age with a regional setting, the island of Zemlia (derived from the Russian zemlya, meaning "land", which is also the basis for the name of the continent featured in the Trails series, romanized by Falcom itself as "Zemlya" but localized as "Zemuria" in the west) that existed in the ancient past of the Lufia series' world, but it also mixes a rather traditional story about elemental guardians and deities with a far more personal and heartfelt Back to the Future-style time travelling element which involves most of the playable cast and the major antagonists.

Indeed, characters are one of Energy Breaker's strongest part, possibly even more so than in the main Lufia games. Myra, Energy Breaker's spirited heroine, is an amnesiac trying to piece together her past while being involved in all manner of intrigues and mysteries throughout the island of Zemlia. In a short while, she will get acquainted with a Doc Brown-like old inventor and his trusty robot, Gulliver, not to mention a mutant ladies' man and a young girl with a troubled past. The lone party member following a more traditional JRPG trope, a valiant knight, is actually enlisted fairly late into the game. The characters never cease to interact during story events, and are pivotal in making the plot feel coherent and cohesive even when its many different themes actually clash in the attempt to fit together. Their differences are also established through visual clues by emphasizing their varied backgrounds, for example by completely changing the context of skills depending on who is using them: Shot, the usual long-range spell, will see characters summoning a lightning bolt, shooting a missile, using familiars to strike, morphing in a defeated enemy to use its magic and so on, all depending on who is casting it.

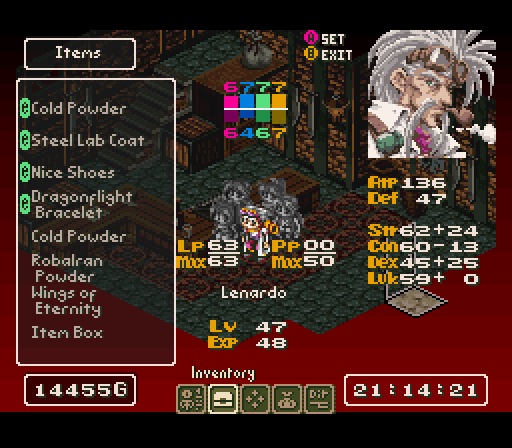

Each character can only have ten items at any given time, but you can find Item Boxes to improve your storage capacity.

As for combat mechanics, the game is also fairly interesting in a number of ways: each character has a pool of Action Points available, with movement taking 5 APs regardless of how far you end up from your starting location. While attacks can be very powerful, skills and magic are absolutely vital and require you to carefully assess how to spend your points, especially since all battles actually have a timer and will end in your defeat if you can't prevail before the turns expire. While most of the time this won't be an issue, it's also an interesting choice that encourage some more planning and tactical diversity, especially since turtling or slow advances mixed with buffs could be the go-to tactics for most battles otherwise. As with many games with stackable buffs, stat-ups are extremely important and a key feature to prevail in the end-game. Despite being a tactical JRPG at its core, the game also has its fair share of dungeons, sometimes with involved paths and secret treasures that require the player to jump in order to exploit the isometric perspective to their advantage, even if it didn’t share the same fascination with puzzles that characterized Lufia 2.

The island of Zemlia existed somewhere in the world of Lufia's past, even if we have no clue about its precise geographical location or the exact time lapse between EB's event and the Lufia series

It’s no surprise this veritable stack of interesting, experimental and sometimes contradictory systems emerged in the context of a troubled development, including cut contents, which explains why the story actually seems like a mix of many different plot threads that sometimes feel underused or distracting. Possibly due to those issues, the game's adventure features weren't implemented in the most convicing and immersive way and, just to name the most obvious example, with possibly one exception I don't recall selecting a different tone during NPC interactions to have really mattered during the whole game.

Sometimes, progressing the story can also be a bit of an headache, especially when the game requires you a mix of time-travelling (which requires going back to a special location) and unlocking conversation topic by talking with NPCs, which isn't always as intuitive as one would like. This is definitely a game where I would have got stuck two or three times if I hadn’t played it more than a decade after its release, with ample documentation available online.

Also, and this is likely to be the game's most obvious flaw to anyone starting it, Energy Breaker has a comically punishing inventory system that lets each character take up just a few items, including equipments and consummables, meaning you will often struggle to take up treasures and hidden collectibles. The game does provide Item Boxes which act as sub-inventories, but they're few and add another nuisance to the inventory system by actually checking all of them as sub-menus in order to see where the game automatically placed the latest loot.

As a final warning to those curious enough to give a chance to Myra’s adventure, one shouldn’t expect Energy Breaker to be some sort of full-fledged Lufia prequel: while it does have some links to the world of Lufia, most of them are extremely vague, with the only obvious one presented as a short cutscene featuring Lufia and Roman during the ending. In fact, the island of Zemlya has its own civilization(s) that are likely set in the world's ancient past, not to mention how I don't recall the mainland being actually mentioned in any meaningful way during the story, making the connections with the rest of the series fairly minimal. Energy Breaker also has its own mythology which doesn't directly tie with the Lufias', though one can surely make a number of conjectures about their connections. One could imagine those references could have actually been added late in development in order to push Energy Breaker to the Lufia fanbase, even if then it would be hard to explain why Neverland didn’t actually market Energy Breaker as a Lufia game, something it wouldn’t be shy to do with the franchise’ following portable spin-offs. In a way, though, this was the right choice, as Energy Breaker has a starkly different, more experimental identity in pretty much every way, and its subtle narrative ties with the Lufia games fit with its mysterious, odd atmosphere.

Note: A previous version of this article was posted on the r/JRPG subreddit on 20\11\2018 by yours truly.