Developer: Capcom

Publisher: Capcom

Directors, or rather Dungeon Masters: Tomoshi Sadamoto, George Kamitani, Magigi Fukunishi

Character designer: Kinu Nishimura

Soundtrack: Isao Abe, Takayuki Iwai, Hideki Okugawa

Genre: side-scrolling beat’em up with plenty of RPG quirks

Progression: non-linear, with stage selection and plenty of branching paths making this one of the most internally varied side-scrolling beat’em ups ever

Developer’s country: Japan

Platform and release date: CPS2 Arcade board (1994), Sega Saturn (1999), PS3 (Capcom remaster, 2013), PC, PS3, X360 (Iron Galaxy remaster, 2013)

Status: As a child, I wasted countless tokens on Tower of Doom in two local arcades in the seaside town where I always spent my summer vacations, managing to finally complete the game the year after I first played it by teaming up with a band of friends (and with the help of the owner’s nephew, which still has my undying gratitude) in Summer 1995, or possibly 1996 as I honestly can’t remember if I first tackled it in ‘94 or ‘95.

Arcade culture is an irreplaceable part of the life of any videogame enthusiasts born in the mid ‘80s and, sadly, one that has disappeared so throughly from most Western countries that describing it has become not just a way to reminisce, but also a sort of historical duty to the new generations of hobbyists. While arcades in my city were mostly places of ill repute that were best left alone as a child, the ones found in the seaside town where I spent my summer vacations were magical places, where I could delve into fighting games that were either unavailable for home console platforms, available through rather mediocre porting efforts or, in the case of SNK’s Neo Geo AES titles, devastatingly expensive and fairly hard to find.

Nowadays games like Super Street Fighter 2, Art of Fighting 2, Street Fighter Alpha, X Men vs Street Fighter, Real Bout Fatal Fury, the yearly iterations of King of Fighters, Street Fighter 3, Last Blade 2, Virtua Fighter 2, Soul Blade and others are seen as evergreen classics or retro-curiosities for fighting game enthusiasts but, back then, they were superb visual spectacles, a joy both to play and behold. Of course, side-scrolling beat’em ups were another main feature, with titles like Knights of the Round, Cadillacs & Dinosaurs, The Punisher and many others costing us more tokens than we care to remember, while others, like Warrior Blade: Rastan III with its dual monitor and impressive sprites, showed how experimental the genre could be even in terms of presentation.

This brings me to one of the very few crosspollinations between my love for tabletop and videogame RPGs and arcade games, Capcom’s wonderful side-scrolling beat’em up-cum-RPG Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of Doom, released in 1994 on CPS2 arcade boards and set in the Mystara setting used by Dungeons & Dragon’s Basic Edition, itself delightfully expanded by a series of geographical modules called Gazzeteers set in countries like the Magocracy of Glantri, the Grand-Duchy of Karameikos, the Orcish clans of Thar and many others that, back then, I was able to find in a now-closed shop, and still treasure to this day. While Mystara was sparingly featured in Western RPGs, like with Westwood’s D&D Order of the Griffon or Warriors of the Eternal Sun, its Capcom-developed arcade adaptations are still the setting’s most famous videogame outings.

Tower of Doom was developed by a team of Japanese D&D enthusiasts that included not just Tomoshi Sadamoto, a Capcom veteran that would end up being a key figure behind Street Fighter 3’s development, but also young George Kamitani, whose aesthetic and mechanic sensibilities as a developer would be heavily influenced by this wonderful formative experience. While previous Capcom fantasy beat’em ups like King of Dragons and Knights of the Round had built a fairly reusable setup for this kind of games, Tower of Doom wanted to be much more than this, stretching its arcade nature to the limit in order to accomodate its RPG roots, all of this embellished by gorgeous sprites, wonderfully animated on complex, interesting and fairly interactive backdrops.

Part of Tower of Doom’s charm obviously had to do with legendary character designer Kinu Nishimura working on its art direction, which feels more balanced in the mix between its Western inspiration and Japanese realization compared with its sequel, Shadow over Mystara, which had a more marked Eastern feel conveyed by subtle details such as hair stylings, facial expressions and some key animations and reminded me of Lodoss Wars, itself a Japanese series heavily inspired by D&D and Western sword and sorcery.

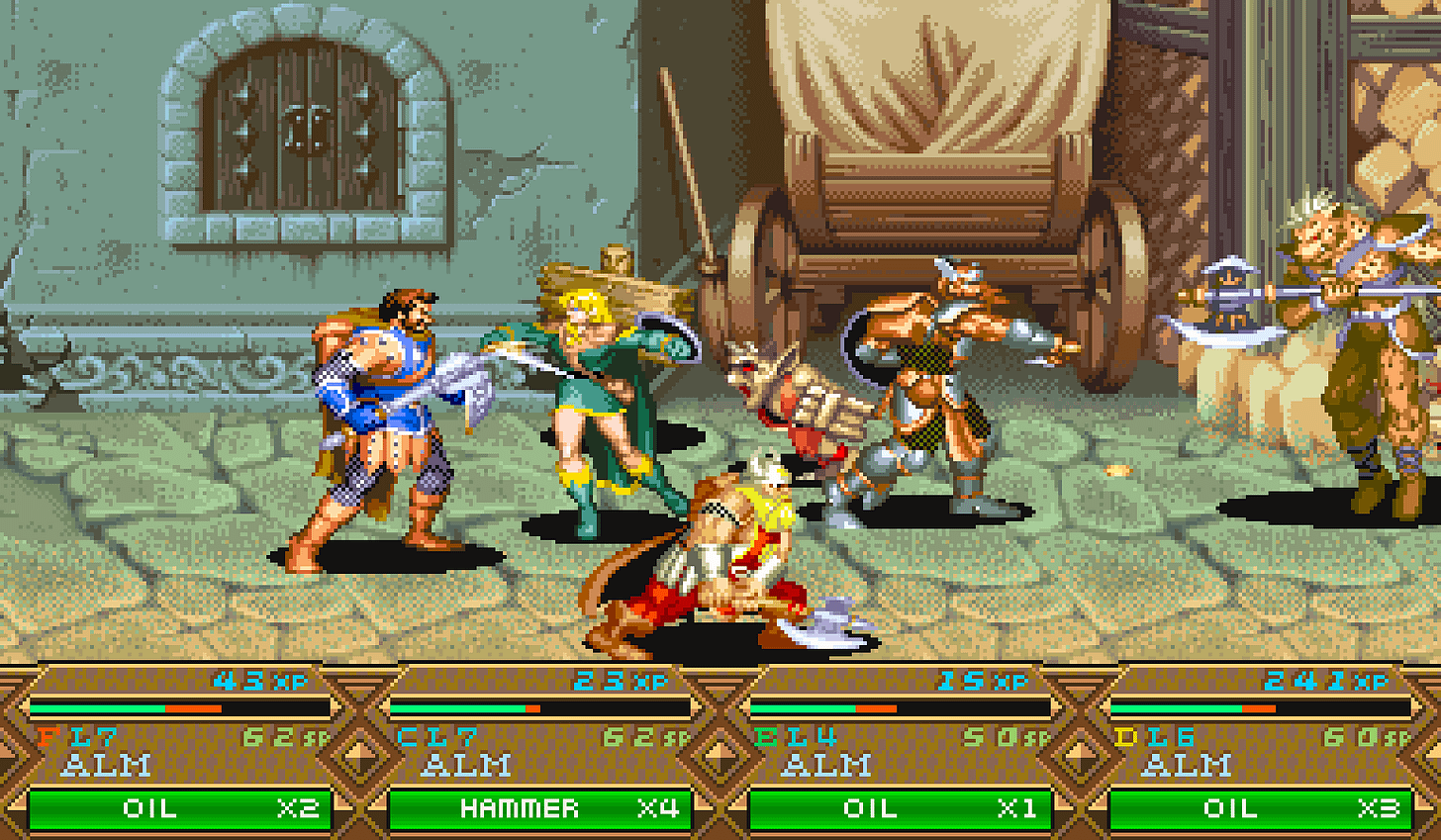

Like most D&D adventure modules of the time, Tower of Doom starts in a tavern, where up to four players (which, given how cramped the joystick real eastate of this cabinet was, likely only worked for us children) could choose their favorite adventurer, either a Fighter, Cleric, Dwarf or lady Elf, before starting the quest. Before lamenting a poor adaptation of TSR’s rule set, it’s useful to remember that in D&D’s Basic Edition Dwarves and Elves were indeed classes, not races, contrary to what happened in Advanced D&D, which already featured multiclassing options for non-human races and convoluted, one-time dual classing for humans, as shown in the videogame space by titles such as SSI’s legendary Gold Box games and, later, by Infinity Engine-era WRPGs.

From the start, tackling Tower of Doom one could feel he was playing something very different compared to most beat’em ups seen before, including apparently similar titles like King of Dragons or Knights of the Round, or later for that matter: not only did this game’s characters have very interesting and dynamic movesets, but they also had a bit of inventory management thanks to a button dedicated to switch the used item or spell (a bit reminiscent of Secret of Mana’s Item Wheel, a feature that Tower of Doom’s sequel, Shadow over Mystara, would end up adopting), letting you store and use all manner of consumable weapons, magical items and scrolls, not to mention memorized spells, adding a surprising amount of complexity to the usual pattern of supermoves costing a bit of HPs. Raining bouncing hammers on laughing Gnolls, trivializing undead enemies by using the Cleric’s Turn Undead skill, blasting iconic D&D bosses like Manticores or Displacer Beasts with the Elf’s level 3 spells, staggering them with Stick to Snakes or seeing Magic Missiles rain on poor Kobolds never got old.

While character growth was mostly linear, with level ups happening between stages just before a first-person point and click shop section let you refill your inventory by spending your hard-earned coins, story progression was anything but: after almost any stage, the players could choose were to go between two, sometimes even three options, visiting completely different levels with their own unique locales, enemies, bosses and treasures, and that isn’t even considering the different paths one could take inside each level.

The party’s composition was also far from irrelevant, with some areas being much harder if you tackled them without the most appropriate spells or items. All in all, despite its arcade nature, or possibly exactly because of it, Tower of Doom felt viscerally like a RPG, not just a videogame RPG but a proper tabletop one, with your fellow arcade friends as party members and Capcom as a cruel Dungeon Master running a hard-as-nails module. This isn’t just a metaphor, given how Tower of Doom’s ending credits listed its three directors as Dungeon Masters, just before Alex Jimenez, the Capcom USA producer who acted as a consultant, liaison and writer for Capcom titles based on Western licenses.

For us children Tower of Doom was indeed a brutal challenge, not just because of the usual coin-munching nature of arcade beat’em ups, but also because of its length and variety, which made every attempt a bit different and unpredictable, with traps and unknown enemies quickly burning our precious tokens and forcing us to retreat, ruminating about how to improve our performance once our parents and grandparents were nice enough to give us another chance by funding our next trip to Mystara. I still fondly remember how we finally managed to complete the game during the second summer after Tower of Doom was introduced in that seaside town, and even then just because we happened to befriend the nephew of that arcade’s owner, which became our local hero by providing us a veritable pile of tokens to finally endure the last dungeon and give Archlich Deimos a much-deserved thrashing.

When the credits rolled, amidst me and my friends high-fiving each other and jumping from joy, I didn’t pay any attention to the name of George Kamitani, and yet, as hinted before, his life as a videogame developer was throughly changed by Tower of Doom, despite him joining its development fairly late, with the humungous Red Dragon boss’ logic as his main achievement. While Capcom went on to develop Shadow over Mystara, the Street Fighter Alpha to Tower of Doom’s Super Street Fighter 2 Turbo, helmed by Tenchi wo Kurau veteran Kenji Kataoka, young Kamitani, who thought obtaining a directorial role in Capcom would have taken too long, was already out as a freelancer making his own name, and game, on Sega Saturn, Princess Crown (which, after a long wait, finally got an English fan translation in late 2024), an action-JRPG that was deeply influenced by his previous work.

Interestingly, according to Kamitani himself, Princess Crown’s volume and even its RPG elements were partly influenced by the necessity to make an impressive pitch to its publisher, Sega, in a market where RPGs were perceived as one of the key battlegrounds in the ongoing war between Saturn and PS1. Even after founding Vanillaware, he quickly went back to his roots with action-JRPGs like Odin Sphere and Muramasa, and consacrated his legacy with Dragon’s Crown, which mixed his own artistic prowess, Tower of Doom’s arcade identity and modern action-JRPG and western hack&slash sensibilities, with delightful results.

Despite being such a seminal effort for Japanese side-scrolling beat’em ups, and indeed for action-JRPG, in that peculiar RPG-adjacent space that also features title like Treasure’s Guardian Heroes, Tower of Doom’s availability has been a sore point. After getting a Japanese port on Sega Saturn with plenty of issues (not just terrible loading times, but also the number of players being cut back to two), the game was basically lost to time until Capcom brought it back on with not just one, but two different porting efforts in the Chronicles of Mystara package.

The first version, available digitally on PC, PS3 and X360 and developed by Iron Galaxy, was a quality port filled with many QoL improvements, but the other, released physically on PS3 just in Japan, was actually crafted by part of the original development team and features a number of upgrades which arguably make it the definitive version, like the possibility to have all four players use the same classes, including palette swapped versions and even a color edit mode. This feature was actually one of the core improvements found in Tower of Doom’s sequel, Shadow over Mystara, which even featured different sprite variants for the same classes.

Unfortunately, while the PC version thankfully is still there in order to preserve the Capcom D&D games, none of those two portings have been made available on consoles of the eight or ninth generation, and likely won’t be until Iron Galaxy retains its license, which is likely one of the biggest reasons my PS3 is still connected. With Capcom working tirelessly to preserve its arcade heritage with a number of awesome collections, one can only hope Tower of Doom and Shadow over Mystara get the same treatment along the way, possibly letting westerners enjoy the PS3 Japanese port we never had a chance to experience without importing.