Developer: Sega

Publisher: Sega

Director: Totoyo (possibly Yasushi Yamaguchi)

Soundtrack: E. Fugu (Fatal Labyrinth)

Subgenre: Roguelike

Developer’s country: Japan

Platform: Master System and Game Gear

Release Date: 1991 (European versions)

Status: Completed in summer 1992 on Game Gear, after far too many failed attempts, then played to the end while shamelessly using save states in July 2022

Back in 1992, two Sega-developed Crystals competed for my Game Gear’s coveted play time: one was Crystal Warriors, my first Japanese tactical RPG, which I will discuss another time, and the other was Dragon Crystal, which had the dubious honor of being my first roguelike. Since at the time I had absolutely no idea about Rogue or the subgenre it spawned, not to mention how I expected at least a bare minimum of narrative when it came to RPGs, even if, at the time, it often meant little more than a couple throwaway introductory text boxes used as a springboard for my own fantasy, to say that child me ended up being a bit disappointed and confused at first would be an understatement.

Dragon Crystal, true to its roots, offered little to no context for its hero being thrown into a gauntlet of thirty randomized dungeon floors, letting its mechanics provide all the emergent narrative the player could need. Piecing together the game itself and its manual which, as it was often the case, managed to add some much-needed flavor, I learned how the unnamed protagonist was just an unfortunate, average guy forced into a foreign world by a magical orb found in a rather shady shop, but that was the end of it.

Thankfully, since as a child I had little to no backlog to speak of, I felt I had to power through Dragon Crystal regardless of my initial shock, slowly discovering the iterative charm of roguelikes, a genre label I would get to know much later, and, with hindsight, how modern and forgiving Dragon Crystal actually was compared to the tenets upheld by the earliest games of his kind, to the point of having some traits that would later be defined as roguelite, long before that term was introduced (and often overused). Admittedly, part of the reason behind young me’s perseverance had to do with Game Gear itself, an handheld that, regardless of how brutally battery-hungry it was, frankly looked like magic to a child whose only portable gaming experiences before that had been the ubiquitous GameBoy and Tiger Electronics’ LCD games.

Another thing I couldn’t appreciate at the time was Dragon Crystal’s intricate development history, linking it to the one of the first attempts at videogame digital delivery and many of Sega’s Sonic Team’s future stars.

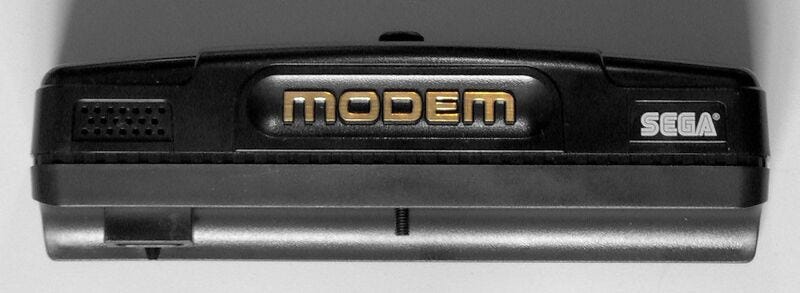

Developed and published by Sega as a multiplatform title for both Game Gear and Master System, Dragon Crystal was actually the sequel (with a generous helping of asset recycling) of Fatal Labyrinth, an obscure 1990 title released on the futuristic Meganet modem digital delivery platform, which used the unique Sega Toshokan (Sega Library) cartridge and the Sega Mega Modem, not to mention the first meaningful attempt at developing a roguelike game in Japan. Fatal Labyrinth was later ported to Mega Drive, even if I ironically ended up playing it only many years after its sequel. Interestingly, Dragon Crystal could still have been released first, since Fatal Labyrinth, despite having a copyright date set at 1990, seems to have been distributed via the Meganet delivery system only a bit later, in 1991, despite bein developed first, which could suggest Dragon Crystal being created in order to salvage the assets of Fatal Labyrinth and provide them a wider public after Sega realized the meager audience for the Sega Toshokan project wasn’t worth the effort. Interestingly, this didn't stop Nintendo from giving a try to a similar concept with Super Famicom's Satellaview five years later, with noticeable releases like Fire Emblem Akaneia Senki, Thracia 776 or Squaresoft's Radical Dreamers.

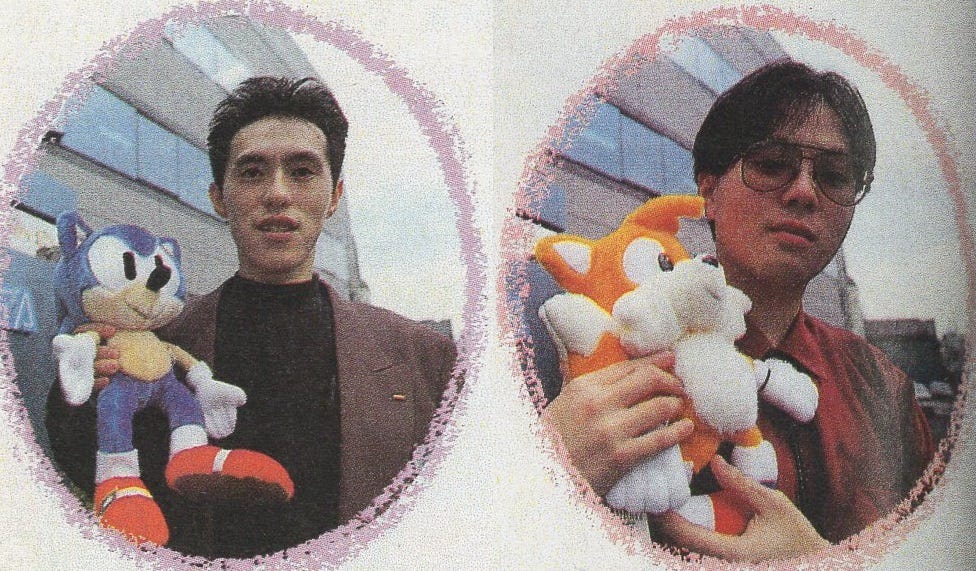

As with some other rather low-profile games released in those years, trying to research Dragon Crystal's development history and team composition is a fairly difficult endeavor thanks to the liberal use of pseudonyms, nicknames and abbreviations in its credits, with the mysterious Totoyo (which can be identified with Sega’s own Yasushi Yamaguchi, later known for his work in the Sonic Team and for creating Tails, whose nickname at the time was “Judy Totoya”) being featured both for graphics and coordination, likely acting as a director of sorts, while E. Fugu, the game’s composer and sound director, can at least be traced back to Dragon Crystal’s predecessor, Fatal Labyrinth.

Since Fatal Labyrinth was one of the first games handled by future Sega legends like Hirokazu Yasuhara and Naoto Ohshima, I tried searching for some hints about their possible role in Dragon Crystal, but unfortunately there’s nothing certain in that regard, and the development may very well have been pushed to other staffers tasked with repurposing Fatal Labyrinth’s code and assets, like the abovementioned Yamaguchi. Then again, as SonicRetro’s user trykaar discovered while disassembling and investigating the code of both versions of Dragon Crystal, its map code is actually the same on both Game Gear and Master System, but is actually quite different when compared to Fatal Labyrinth’s, possibly due to the latter having some different systems like hidden doors and a liberal use of traps.

In fact, if we consider the timeline of 1990 and 1991 Sega releases, while Sega AM8 (later renamed Sonic Team) itself wasn’t officially associated with Fatal Labyrinth or Dragon Crystal, one could theorize some of its staffers, which had indeed worked on Fatal Labyrinth, couldn’t devote more time to its sequel because, in the meantime, they were focused on Sonic the Hedgehog, which would explain why Dragon Crystal was left to a skeleton crew of sorts.

As for Dragon Crystal itself, one could say its most bizarre trait is surely the titular dragon, a companion our hero finds himself hauling for the whole game, first as an oversized egg, then as a growingly menacing monster that… doesn’t actually do anything, aside from stopping enemies from fully surrounding the hero, which isn't even that helpful considering how many late-game monsters have long-distance attack and can easily circumvent that one-tile barrier. The game, after all, isn’t afraid of throwing nasty tricks at the players, as this subgenre demands: warp points can get you to the busiest area of a new floor, nearly surrounded by enemies, monsters can and will permanently ruin your stats and equipment and inflict multiple status effects, including one that resets the fog of war making you explore that floor all over again, while a traditional stamina system based on picking up food provides your usual HP regeneration, turning to depletion once your food stat goes to zero.

Finding equipment is key, as is switching them depending on the situation, with a whole class of blue weapons providing overwhelming advantages when fighting certain types of enemies (Hardbreaker being particularly useful to reliably kill the metal orbs, for instance) and the above mentioned equipment-destroying enemies making it imperative to use weak tools against them, if one cannot avoid those troublemakers altogether. Consumables, provided in different flavors like books, wands or potions, are also tricky since they need to be identified by using them at least a single time, which means the best way to proceed is actually to spam them in the very first levels, when even their worst drawbacks are less impactful, so that their effects are fully accounted for once you get to the end game.

The roguelite bit, instead, is associated to money, which, in a game without any kind of shop, is used only to buy continues at the game over screen, having your character restart from the floor where he was cut down, albeit without any unequipped item. Obviously, this makes the game more manageable and lets it stay nasty without getting too overwhelming in its challenge, even if some roguelike purists could find it too much of a crutch. Amusingly, the gold system was actually introduced in Dragon Crystal’s predecessor, Fatal Labyrinth, where its only use was apparently to improve the hero’s tomb and funeral service in the Game Over screen.

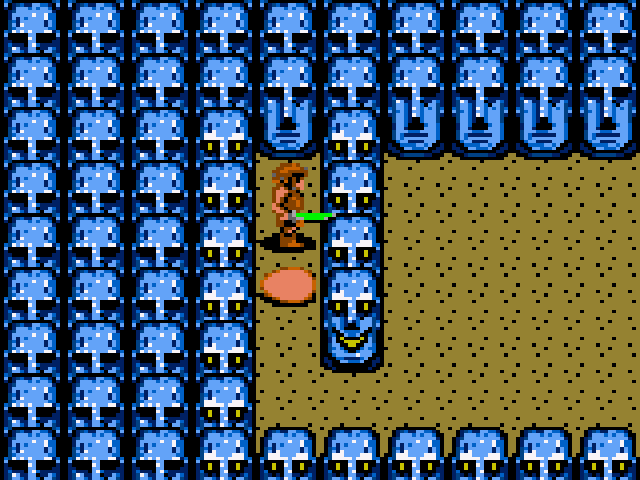

Aesthetically, Dragon Crystal uses randomized tilesets for each floor that change once the hero explores an area and find new rooms. There are also a lot of differences between the Master System and Game Gear versions in this regard, like the former having crystal and mushroom levels the latter lacks, among others, though the funniest will always be the Moai Easter Island-style statues tiles turning their stoic frown into an awkwardly happy smile once you remove the fog of war.

While Dragon Crystal can be beat in under two hours if one is lucky and proficient enough, at the time I found it endlessly frustrating to see Game Gear’s batteries depleting well before I had a chance to get further into the game, especially since, as mentioned before, Game Gear was a relentless devourer of AAs unless you had a chance to plug it to a charger, which was usually when you would transition to play a home console instead. Still, power issues aside, Dragon Crystal was extremely well suited to handheld consumption, given its lack of narrative and its bite-sized floors. In fact, the coolest bit, aestethically speaking was placed right after the credits, as I discovered when I finally managed to snatch victory during the summer, since the game regaled you with a fairly pixelated artwork of the hero in full plate armor that was way better than anything else featured in the game itself in terms of art direction. I would like to pin that ending still on Naoto Ohshima’s talent, but unfortunately there’s no way to confirm it was one of his early works. Dragon Crystal’s Master System port, as I discovered much later while researching that version, had its own illustration (a bit less impressive, I think) used in the same context.